The UpStairs Lounge Fire Killed 32 People. Its Legacy Still Haunts Black Gay New Orleans

The upcoming 50th anniversary of the Stonewall Riots in New York City next month is causing a half-century look-back at the American LGBT rights movement.

Behind the triumphalist narrative commonly posed—that of the long but inevitable march to freedom for gay white males—is a history of lost atrocities and uneven advancement, especially for more marginalized groups in places like the “Queer Capital of the South,” a.k.a. New Orleans.

There was a time in New Orleans when homosexuality was illegal, and “gay” was a dirty word, but somehow being black and gay made you negligible to other gays, other black residents and the city at large.

For example, when the UpStairs Lounge, a gay bar, burned to ashes in 1973 killing 32 people, it sparked an effective crackdown on the bar scene. Unsurprisingly, the first casualty in that crusade was the black gay bar down the street.

“Dinge” did not mix with “snow” openly, especially not on Bourbon Street. That was unspoken law in the gay subterranean of New Orleans in the 1970s. “Dinge” was slang for black homosexuals, reference to dirt—language now pejorative and offensive but then considered to be street-speak, a crude but commonplace descriptor.

“Snow,” by contrast, meant white and referenced antiquated notions of pureness in an era that eroticized race. Such terminology had been appropriated from national gay culture—appearing throughout queer literature such as Andrew Holleran’s Dancer from the Dance and Larry Kramer's Faggots—but given new context in the racial dynamics of the Creole South.

For example, two black longshoremen who crossed racial lines to frequent the UpStairs Lounge, which served mostly working-class white patrons on the border of the French Quarter, went by the nicknames Smokie and Cocoa as reference to their skin tones.

Buddy Rasmussen, the white bartender and manager of the UpStairs Lounge, was known to be especially friendly to all comers, even letting women into the bar at a time when gays and lesbians were strictly separated.

The crew of the UpStairs Lounge had an anthem they liked to sing at the piano that summed up their unique outlook: “United we stand, divided we fall.” So went the chorus. So they did. The UpStairs Lounge culture had proven so attractive to open-minded gays, such a queer change of pace for New Orleans, that it received special mention in Bob Damron’s Address Book, an annual travel guide for the discreet gay vacationer.

In keeping with Damron code, to protect gay travelers from criminal exposure, the UpStairs Lounge received “(*)” status to signify “Very Popular.” In fact, the Up Stairs Lounge was so popular that summer that it attracted a black visitor from Atlanta named Reginald Tubbs.

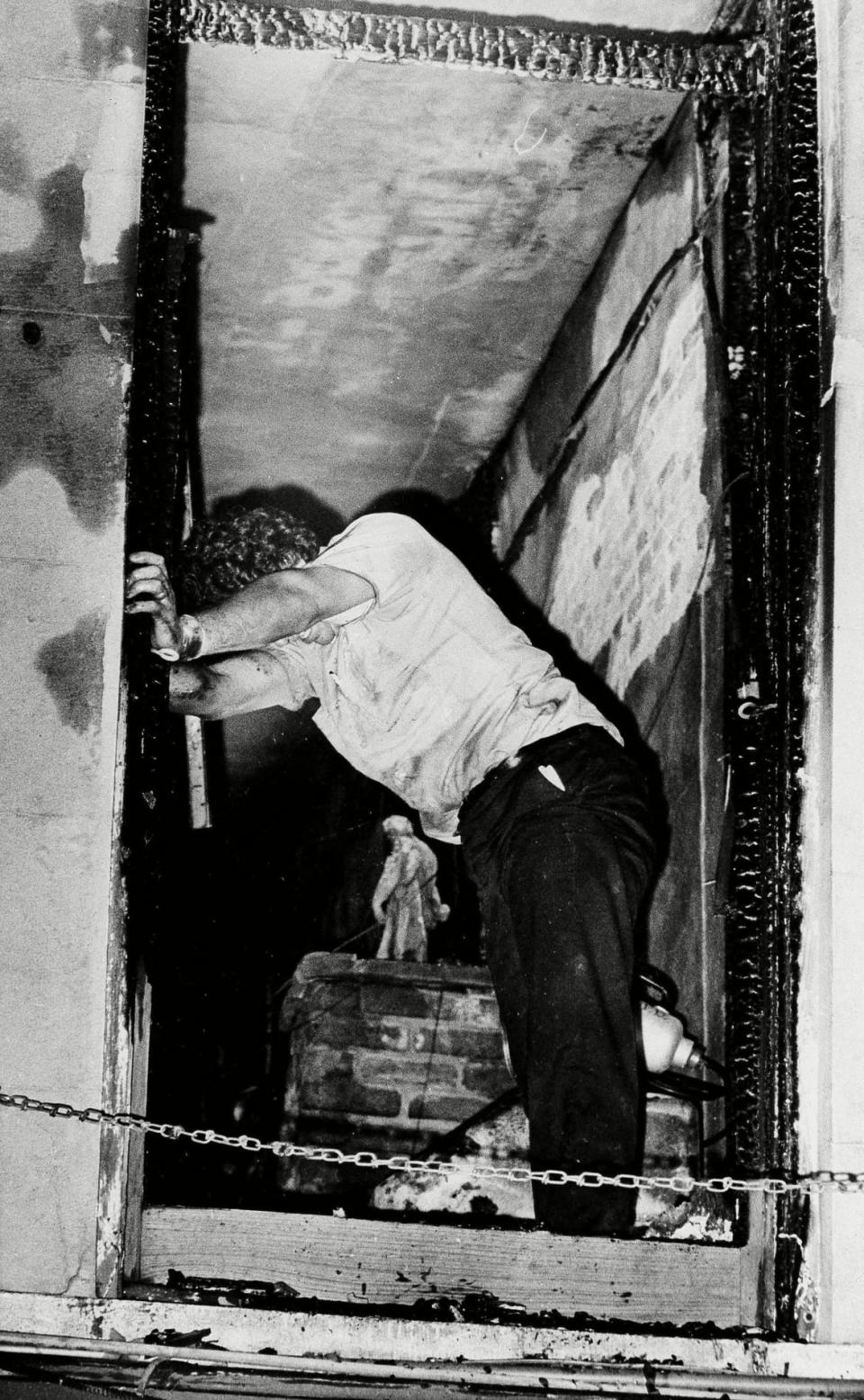

Firemen give first aid to survivors at the UpStairs Lounge.

When fire struck that teeming bar on the night of June 24, 1973, with approximately 90 patrons gathered for a Sunday drink special called the “beer bust,” men like Tubbs would be lost in the pandemonium.

Within minutes, flames claimed the lives of 29 patrons, with three others doomed to agonizing deaths in a hospital burn ward. It was the deadliest fire on record in New Orleans history, yet few knew how to react publicly to a homosexual establishment burning to ruin, much less an interracial one.

‘The racial politics, for lack of a better word, were terrible’

Outside the occasional oasis, black and white gays had mostly kept to their own spaces. “People think gay is one big loving family,” recalled Rusty Downing, a black gay New Orleanian. “No, gay is a microcosm of the real world. People were raised by who they were raised by. They still have those fears, those ‘-isms’. The only thing we have in common is we like the same sex.”

None of the gay Mardi Gras krewes, or fraternal orders that hosted theatrical masque balls during Carnival season, had black membership in the early 1970s. “The racial politics, for lack of a better word, were terrible,” recalled Michael Hickerson, a lifelong New Orleanian who is black as well as gay. “The majority of the bars were predominantly, if not entirely, white gay bars. There were black gays around, obviously, but it was very difficult for us to get in.”

Discreet white homosexuals enjoyed the virtual run of the French Quarter, with more than 20 gay bars in close proximity. Black gays, by contrast, mostly frequented the few black gay bars in town like Charlie’s Corner or the Safari Lounge, a second-floor saloon on the corner of Iberville Street and Royal Street.

“Coming out as gay in the black community, you’re struggling to explore,” recalled Hickerson. “You’re trying to find out where ‘it’ is. You sense that ‘it’ is out there, but you don’t have anyone to show or tell you. So I found the Safari Lounge on Royal [Street]... Safari was up stairs, and I ventured up there very afraid.”

Within the Safari Lounge in 1973, men like Hickerson found a saloon teeming with black men, plus black managers named Priscilla and Roosevelt Porter.

Patrons of the Safari would flirt beneath the blare of live music and dance almost lip-to-lip. “I remember a T-shaped stage and gorgeous black drag queens, queens you never saw elsewhere,” recalled Regina Adams, a white New Orleans nightclub performer who, in 1973, had a black lover.

There would be the occasional boldfaced “snow” gay seeking “dinge,” as the terminology went, as white gays could cross certain boundaries that black gays couldn’t.

Hickerson recalled seeing a group of whites at the Safari once, for example, when you’d never see more than one or two black patrons at the UpStairs Lounge. But the Safari hadn’t always been a gay bar. When it opened in 1965, the Safari Lounge boasted a wild and freewheeling reputation.

Ken Mitchell, a black gay New Orleanian, remembers its vibe as being “kind of seedy.” A proprietor named Helen Williams hosted jazz acts featuring local greats like saxophonist Alvin Tyler and pianist Ellis Marsalis, as well as then-controversial drag performances.

But the all-hours company could be rough and attract the authorities. Police regularly found armed robbery suspects in the establishment. In 1968, the New Orleans vice squad raided the bar and arrested a 21-year-old white male for wearing clothes of the opposite gender, as well as a black couple for dancing lewdly.

Subsequently, the owner Helen Williams faced petitions to suspend the Safari Lounge’s liquor license. Clearly, she beat the rap, as the party kept on rolling. By the early 1970s, the Safari crowd had transitioned from mostly straight or bi-curious swinger couples, who dabbled in alternative sexualities, to mostly gay men.

“More gay people would come, more straights would leave,” as Hickerson describes the process. “Before you know it, it became a black gay bar.”

A new owner, a black man named Hayes Littleton, formally took over the establishment in March 1973, and he ran a much tighter ship. When the Times-Picayune, the local newspaper of record, inaccurately reported an armed robbery at the Safari that May, Littleton made sure to correct the record, stating “no robbery occurred there… as reported by police and published in Saturday’s edition,” to protect the bar’s new standing.

Most of Littleton’s gay patrons were closeted to their families. Many wore wedding rings. To leave the bar, they’d run down the staircase one by one and duck to the left so as to pretend to exit from the nearby Playboy Club.

Ironically, the Playboy Club only rarely welcomed the odd black patron, usually an out-of-town celebrity. The preferred method of exit for white gays—dashing from a gay bar into an idling taxi—wasn’t available to black gays because cabs wouldn’t serve black customers.

“If you called a taxi service, a United Cab, for a black customer, they would just drive off,” recalled David Williams, a white gay New Orleanian who bartended in French Quarter establishments throughout the 1970s and 1980s. “They would drive by, see a black man waiting and leave him at the curb. You could offer to tip that driver 40 or 50 dollars, it wouldn’t make a difference.”

Just down Iberville Street, cabs would regularly visit the UpStairs Lounge to scoop up boisterous patrons. Bartender Buddy Rasmussen had developed a system whereby a cabbie on the ground floor could ring a bell that sounded throughout his second-story establishment to notify a patron that his ride was ready to go.

In many ways, the new Safari Lounge stood as a black counterpart to the UpStairs Lounge—just a block away and up a different staircase. Much like the UpStairs Lounge, the Safari Lounge thrived, receiving mention in that year’s Bob Damron’s Address Bookwith the code “(B)(RT),” which meant “Blacks Frequent” and “Raunchy Types.”

It’s important to note, within this racial milieu, that “Raunchy” could be reference to the infrequent case of biracial dating at a time when black gays who sought white partners were singled out as “snow queens,” and white gays who sought black partners became known as New Orleans “dinge queens.”

Most of the UpStairs Lounge crowd, white wage-earners who lived paycheck to paycheck, couldn’t afford to challenge anti-gay attitudes or racial stereotypes pervading the city for fear of exposing their sexualities in the process.

The Safari crowd, further oppressed by Southern racial codes, would face swifter consequences if they did speak up, and so they did not.

Though highly accessible, homosexuality remained easily punishable by state anti-sodomy laws and local harassment ordinances, which could result in not just arrest but also expulsion from social clubs and churches or the loss of one’s job when an arrest for a sex crime became publicized in the Times-Picayune.

What’s more, black gays of the era continued to be isolated two-fold by the white gay community and the black church community.

“Within the black community, there was no acceptance of gay rights because of the black churches,” recalled Larry Bagneris, a black gay New Orleanian, in an interview for my book, Tinderbox: The Untold Story of the Up Stairs Lounge Fire and the Rise of Gay Liberation. Yet, as Bagneris noted with irony, “The civil rights movement began in the Black churches.”

Most black gay men knew to conduct themselves so as to never disgrace their kin. “Black gays, we’re close to our families,” opined Michael Hickerson. “And we’re not going to do anything that will cause some kind of disruption or bring shame to the family, especially a father.”

Preserving honor, in a situation where a cousin’s or a son’s sexuality was understood but not discussed, depended upon private secrets never being exposed. A blackmailer, who could come in the form of a con artist or a former lover or a desperate friend, could exploit these vulnerabilities, and horror stories did circulate.

Perhaps that’s why black gay men of the middle or upper classes, men with fortunes to lose, often avoided the bar scene entirely through membership in clandestine social clubs, which held meetings in private homes.

“I remember being part of a group called Fourth World,” recalled Ken Williams, who came out to his family in 1974. “It was all gay men, all black, but it was very low key. I mean, they didn’t identify publicly as gay, OK, but all of the members were.”

Of course, queers throughout Crescent City were sexually curious throughout the 1970s, an era of renowned promiscuity before the onset of AIDS, and often dated or cruised interracially, especially on the prowling grounds of City Park or Rampart Street. “It wasn’t out in the open,” Hickerson opined. “And, when it did happen, it was the late night trick.”

Some rules could be negotiated through a gay bar culture run on friendships. “But still it was a white man’s community,” qualified Hickerson, “a gay white man’s community.” A few light-skinned black gays, for example, could be permitted to “pass” in the daytime in a tony white setting like Café Lafitte in Exile on Bourbon Street so long as they didn’t declare their race.

For example, a lifelong New Orleanian named John Wilson, who was often referred to as light-skinned black or “passé blanc” (a New Orleans expression applied to French Creoles of color that translates to “passing white”), could pull up his in pink Cadillac outside Café Lafitte in Exile and enter the establishment without hassle.

“I never had any problems getting into the bars because of my skin color,” said Wilson. “I mean, there were people who were friends of mine that knew what I was, but there was no issue made of it because I could be mistaken as white.”

Managers wrongly equated the appearance of black men like Wilson with being of a non-black racial background, although Wilson had grown up attending segregated black schools and riding in the "Colored" section of the streetcar.

“They had a sign on the door at Lafitte’s,” recalled Regina Adams, “It said, ‘No Blacks, No Fems, No Women.’” When Tommy Hopkins, owner of Café Lafitte in Exile, deemed a patron to be “too black” for his liking, Hopkins would raise a hand with three fingers extended. That gesture signified to the doorman that a patron would need to produce three forms of ID to gain admittance.

“First off, someone wanting your ID was a signal,” recalled Michael Hickerson of a time when carrying identification posed a liability for men in the closet. “This was the 1970s in a city of 24-hour bars. No one carried IDs. If you even had an ID, to keep you out, they’d ask for two. Then if a person presented two, they’d ask for three. And make it more and more difficult.”

It should be noted that in situations where a man like Hickerson would be carded, a man like John Wilson wouldn’t, just as when a man like Wilson attempted to drink at a black gay bar like the Annex on Burgundy Street, he would receive different treatment.

“If people didn’t know me,” recalled Wilson of his visits to the Annex, “they would think I was Caucasian, and I would get looks.” Racial binaries could break down in confounding ways throughout the Crescent City.

Only a few fringe establishments like the UpStairs Lounge were brazen enough to encourage interracial mingling. “It wasn’t a perfect kumbaya,” noted Frank Perez, local gay historian and co-author of In Exile: The History and Lore Surrounding New Orleans Gay Culture and Its Oldest Gay Bar. “But it was highly unique for the times.”

For example, a black former Jesuit seminarian named Reginald “Reggie” Adams met the love of his life, a white patron who was then experimenting with various female personae, at the UpStairs Lounge.

Bartender Buddy Rasmussen had encouraged their flirtation and became close friends with the couple when romance blossomed. It was Reggie who gave his new lover the name she would use for the rest of her life: Regina.

“I visited Reggie’s family in Dallas that June and met his mother,” recalled Regina. The couple planned to have a non-legal conjugation ceremony, to signify their commitment, at the UpStairs Lounge that August. Regina had even dared to bring Reggie to Café Lafitte in Exile.

“He was the first black man I ever saw drink in Lafitte’s,” recalled Adams. “And they only let him in because was with me. He sat way at the end of the bar, next to the sound booth, where people couldn’t see you from the door.” Encountering such a pair as Reggie and Regina, bridging race and gender in a communal bar setting, was an anomaly.

Creole code had succeeded in squelching most attempts at gay activism in New Orleans, which spread to Louisiana after the 1969 Stonewall riots. But certainly, the gay Mardi Gras krewes stood as a bright light of contrast to the atmosphere of oppression.

The founding of gay krewes such as Yuga (1958), Petronius (1961), Amon-Ra (1965) and Armeinius (1968) actually predated Stonewall.

“Mardi Gras was the center of the gay community,” recalled Hickerson. “If you belonged to one of those organizations, then you belonged.” These semi-closeted societies held annual masque balls to packed auditoriums. But invitations came carefully guarded, with requests for “no pictures please” so as to preserve the privacy of membership.

Thus did krewes endure as the city’s most powerful gay institutions. Amon-Ra, for example, proved powerful enough to be courted by politicians like Harry Connick in his 1973 run for District Attorney.

So when fire exploded through the windows of the UpStairs Lounge on June 24, 1973 in what looked like an apparent act of arson, the straight and gay population of New Orleans reacted with both confusion and humiliation.

Just imagine the street gossip: the deadliest fire on record in New Orleans history had struck a gay bar frequented by men of both races. Jokes that circulated around the French Quarter spoke of the “flaming queens” who’d “burn their dresses off.”

Though UpStairs Lounge bartender Buddy Rasmussen had mere seconds to bravely guide at least thirty patrons out an emergency exit, those trapped inside like Rasmussen’s lover Adam Fontenot had perished gruesomely.

“I remember there were guys gathering in gay bars, at Lafitte’s, and it became a point of conversation for the night, this cataclysmic event,” said John Wilson.

A rescue worker leans against a charred window at the UpStairs Lounge. The worker was helping remove the charred bodies when he apparently couldn't face it any longer.

But few straight New Orleanians were willing to acknowledge the city’s large gay subculture in the wake the disaster.

The notion that “the city has an active homosexual community which does not magically appear at Mardi Gras,” as wrote a Times-Picayune journalist, lingered contentiously. When forced to react to an emergency event, many locals could barely find common humanity with so-called “sex criminals,” much less concern themselves with racial discrimination among those who’d perished while conspiring to commit sex acts that the average American equated with rape.

Major Moon Landrieu and Governor Edwin Edwards, white Louisiana Democrats who counted heavily on the black vote, declined to make statements of sympathy for the UpStairs Lounge dead or declare citywide or statewide days of mourning.

The chief suspect Rodger Dale Nunez, an UpStairs Lounge patron ejected from the bar screaming “I'm gonna burn you all out” minutes before the fire began, later would confess to a boyfriend that he lit the blaze out of spite.

Police never questioned or arrested Nunez, though he was at one point taken into police custody and then left without guard at a local hospital. Nunez supposedly eluded authorities when he left that hospital and fled to his childhood home, where he frustrated efforts to relocate him despite the fact that his social security ID listed that home address. He would later take his own life.

The gay Mardi Gras krewes, courted by powerful politicians, made no statements to the press about friends and acquaintances who’d perished; not even their leadership could risk such openness.

Owners of local gay bars grew incensed when crowds dropped “one-third to one-half” of their usual size, according to a local newspaper called the Vieux Carre Courier, and discouraged talk of recent deaths.

It’s worth questioning whether men like Café Lafitte in Exile owner Tommy Hopkins, whose bar had been visited by UpStairs Lounge patron Reggie Adams weeks before, was made bitter or less sympathetic towards the destruction of a competitor bar whose racial attitudes had affected his own.

Front-page stories on the fire in the Times-Picayune the next day didn’t use the word “homosexual” or “gay” to describe the UpStairs Lounge patrons. Most newspaper editors policed and censored the word “gay,” in this era, because it equated happiness with an illegal lifestyle.

The Louisiana Weekly, New Orleans’ black newspaper, wrote, “It is not know if any of the victims are black, but a number of black patrons had been known to frequent the bar called ‘The Upstairs.’” Unsurprisingly, no follow-up stories appeared in the pages of The Louisiana Weekly, much less national black publications like The Chicago Daily Defender.

UpStairs Lounge owner Phil Esteve, a white gay New Orleanian, stood in the ashes of his bar that Tuesday, two days after the fire, and criticized attempts by national gay leaders to turn the UpStairs Lounge fire into a political call for Gay Liberation and the dead into martyrs.

“This fire had very little to do with the gay movement or with anything gay,” Esteve insisted to The Philadelphia Inquirer. “I do not want my bar or this tragedy to be used to further any of their causes,” he continued.

Esteve, silent as the coroner struggled to identify fire victims and as families struggled to receive religious funerals for the UpStairs Lounge victims, collected at least $25,000 in fire insurance after the blaze. He used that money to open another gay bar within the year called the Post Office.

One small note of personal reprieve came for Bagneris, who was closeted to his family and out of town at the time of the tragedy.

Bagneris’ mother was made more open and accepting by the fire. “I remember my mom saying to me on the phone,” Bagneris recalled in an interview for Tinderbox, “when she was telling me this awful story, ‘But these were people that shouldn’t have been treated that way,’ which was encouragement to me to come out [to her].”

Tragically, Reggie Adams would be tentatively identified among the UpStairs Lounge dead by that Wednesday, June 27.

Regina, Reggie’s lover, had not seen Reggie since she left him near the bar’s grand piano on the night of the blaze. Regina remembered needing to dash to their nearby apartment to get a checkbook for a friend’s birthday dinner.

Ever genteel, Reggie had offered to run the errand himself, but he’d only just started a scotch and soda served by Buddy Rasmussen or his busboy Rusty Quinton, and Regina had insisted that he stay put. They’d pecked and parted with “I love you,” and she’d run down the staircase.

Regina was gone for less than 20 minutes, during which time someone lit a fire in that very stairwell. The taxi buzzer rang inside the bar, and flames exploded in a fireball that cleaved forty-four feet across the room when someone opened the door to check downstairs.

Fire met oxygen and fuel. Lambent flames pinned Reggie’s body by the far windows, which had been sealed with iron bars as a safety measure approved by fire inspectors. He died of third and fourth degree burns across 95 percent of his body surface, according to the coroner’s report.

Minutes later, Regina walked the final block down Iberville Street and witnessed the inferno herself. In an almost out of body experience, she searched for Reggie among the teeming crowds of gawkers and spectators as firefighters doused the flames. She screamed his name.

Regina went to Charity Hospital when she couldn’t find him among the survivors, but she didn’t ventured down to the morgue to help identify Reggie’s body because, in her words, “There was nothing left to ID.”

Flames were hot enough to char much of Reggie’s external skin tissue, which likely led to investigators mistakenly identifying him as “an adult white male” in a written report, but the coroner did ultimately mark his body as “N,” shorthand for the 1970s legal term “Negro.” The coroner eventually confirmed his death using dental records.

“In August, his mother came in town to pick up his body, and that’s the last I ever saw of any of them,” recalled Regina. “Instead of coming for a wedding, she came to bury him.” Reggie’s wake would be held in Dallas at 11 a.m. on a random Wednesday. Regina did not attend.

Throughout her ordeal, it must be noted, none of New Orleans’ black churches or civil rights organizations came to her aid. Likewise, none of the local black newspapers wrote Reginald Adams an obituary or conducted an inquiry into his death and the subsequent police investigation, which named no culprit despite the emergence of a chief arson suspect.

The city’s Human Relations Commission, tasked to handle civil rights matters, did not inquire about Reginald Adams despite the fact that half of the committee was black.

Furthermore, when New Orleans police listed another possible black victim “possibly dead as a result of the fire,” a man named Reginald Tubbs visiting from Atlanta, no leader of the local black community adopted his cause.

Afterwards, when police eliminated Tubbs as a candidate, only few members of the local Metropolitan Community Church, a gay-friendly congregation that lost one-third of its membership to the fire, continued to publicly insist on Tubbs’ presence at the UpStairs Lounge.

Both authorities and the mainstream press ignored these voices, as homosexual Christians were then considered to be a criminal element beyond the body politic.

Thus, when the last three bodies from the UpStairs Lounge, labeled as unidentified #18, #23 and #28, became transferred to city custody by July 31, no one in the white or black heterosexual power structures stepped forward to prevent their being interred without markers in a remote potter’s field.

When the Metropolitan Community Church attempted to take responsibility for the bodies in a last minute appeal, the New Orleans City Attorney denied their claim. One identified fire victim, a white World War II veteran named Ferris LeBlanc, received burial beside the unidentified because authorities couldn’t easily locate his family, who resided in California.

The identities of the final three UpStairs Lounge victims, and the presence of Reginald Tubbs at the UpStairs Lounge according to witnesses, remain puzzling question marks decades later.

All the while, the Louisiana State Fire Marshal led the New Orleans Fire Department on a crackdown of fire code violations in and around the French Quarter. But no one raised alarms when authorities specifically targeted the Safari Lounge in their crusade.

Indeed, fire inspectors ordered the Safari Lounge, described by the Times-Picayune as “a second-story walk up similar to the ill-fated UpStairs bar,” closed immediately despite owner Hayes Littleton’s insistence that the bar had no previous code violations.

Firemen and rescue workers look up at the burned-out UpStairs Lounge.

The bar, shuttered by that Thursday, June 28, would never reopen as a black gay oasis or a venue for black drag and never appeared again in the pages of a New Orleans phone book. “No black man wanted to be outed,” explained Hickerson. “So you could just do something like that, and no one would say anything. We’d just go somewhere else… Unfortunately, when they close down the black gay bar, you can’t go to the white ones either.” Thus did one fire succeed in making two gay bar cultures vanish on the same city street.

National gay activists like Troy Perry and Morris Kight, who traveled to New Orleans in the week following the fire to hold memorials and begin fundraising efforts for the victims, were too preoccupied with visiting hospitals and battling the ire of bar owners like Phil Esteve and Tommy Hopkins to grasp racial nuance or observe a blatant act of predation on the Safari Lounge, the only bar shuttered instantly in the fire inspection campaign.

In this era, it seems, the black, gay and black gay communities were so isolated from each other that they failed to see common plight or come to each other's defenses. Divided, they often fell.

The Advocate, the legendary gay news magazine publishing news of the New Orleans fire from Los Angeles, got the story of the Safari Lounge wrong entirely.

“Another second floor bar on Iberville, a block from the UpStairs, the Safari Lounge, was closed by the Fire Prevention Bureau in the wake of the UpStairs for alleged fire code violations,” reported the paper. “The Safari is not gay.”

It took the Philadelphia Inquirer, an ultraliberal East Coast newspaper, sending its own reporter to the Big Easy for a few days to accidentally stumble upon the Safari and identify it as “a predominantly black gay bar.”

Some patrons from the Safari Lounge eventually migrated to a club abutting the highway called Tucky’s Dome, which they slowly converted into a Black gay disco.

“At Tucky’s Dome, they would even play slow records, and guys would slow dance with each other,” recalled Ken Mitchell with fondness. “It was fucking fabulous,” recalled Hickerson. “Fabulous. I remember so many people who are dead who used to frequent that bar… They were dancing from the ceiling.”

Regina entered a prolonged state of mourning as she laid out Reggie’s clothing on their bed each morning. Bartender Buddy Rasmussen, mourning the loss of a lover named Adam Fontenot, also disappeared from the public view for a span of weeks.

But Regina and Rasmussen eventually did reemerge into gay life. Regina became a celebrated nightclub act, and Rasmussen tended bar at the Post Office, former UpStairs Lounge owner Phil Esteve’s new establishment. Rasmussen embraced his membership in the Krewe of Amon-Ra and took refuge in the annual revelry of gay Mardi Gras.

Talk of the deadly blaze dissipated, and the city moved on. Investigations closed without answers and remain officially unsolved.

‘I really think that Black & White Men Together helped get rid of that negative terminology’

In 1974, John Wilson used his “passé blanc” status to covertly integrate the gay Krewe of Olympus, which made him the first black member of a gay Mardi Gras organization in New Orleans.

“Some knew what I was,” insisted Wilson, “but those who did never verbalized what they knew.” Wilson also knew better than to verbalize his point of difference, which would make his race a vexing issue.

Wilson, who had a bodybuilder physique, was frequently asked to be a “page,” or scantily clad escort for drag queens, at gay Amon-Ra Mardi Gras balls throughout the 1970s. “I had a 28-inch waist and a 38-inch chest, so they liked that,” Wilson explained with a laugh.

“I had the appearance of being white,” he continued, “and therefore they didn’t think it was going to be a problem with the venue or people who would attend the balls or their fundraising events.” But Wilson never fully tested the limits of his ruse by trying to become an Amon-Ra member.

In the early 1980s, Regina legally changed her name to Regina Adams, taking Reggie’s surname to honor her the man she once wanted to marry. Around her, throughout New Orleans, gay racial attitudes were slowly evolving. By 1982, locals founded a New Orleans chapter of Black & White Men Together (BWMT), a national organization that provided both a venue and support group for gay men interested in interracial dating.

“There were still things like ‘dinge queens,’” recalled Hickerson. “But I really think that Black & White Men Together helped get rid of that negative terminology.” Rusty Downing attended BWMT meetings, which he called “stitch and bitch” sessions where words like “snow queen” would be used with humor, so as to demystify interracial courtship.

Hickerson joined the Louisiana Gay Political Action Committee, called LAGPAC for short, to advance gay politics in the state.

“You know, politics is one of those things where they use you, and you use them,” he recalled. “I became their face in the gay community. I understood that. But I also understood how I was opening up doors and making a tiny bit of difference by putting black people on the forefront.”

Yet when LAGPAC took up a vote in 1982 to support a local newspaper ad that criticized the “harassment and humiliation our fellow [black] gay men and women suffer as their civil rights are violated in the doorway of the gay bar” and demanded “a stand on this issue,” the predominantly white male board voted down the measure.

Not coincidentally, LAGPAC’s primary financial sponsors happened to be the owners of the white gay bars maintaining these racial policies. So it went with half-measures.

That year, Michael Hickerson formed the Krewe of Polyphemus for the purpose of having one gay Mardi Gras krewe in town that explicitly accepted Black members.

Ken Mitchell joined LAGPAC to channel his feelings of anger and resentment constructively. “It was a strong organization, lots of participation,” recalled Mitchell. “The only lack of participation was from minorities, African Americans and Latinos. And we tried to figure out why, brainstorming, and we came up with the idea that we’d do better separately because there was a lot of trust issues between the communities.”

So birthed the black gay advocacy organization Langston Jones, along with a bimonthly discussion group for black gay New Orleanians called Man Talk.

“A lot of black gays—especially during the '80s when the racism was more overt, when communities were fighting for gay rights—said, ‘I’m going to fight for equal rights, not gay rights, because the gays have shown me no difference,’” recalled Rusty Downing. Many gay black men who fought for equal rights, however, did not achieve equal status with straight black men when certain hurdles fell back.

For example, Ernest “Dutch” Morial, the first black mayor in New Orleans history, publicly supported those with HIV during the height of 1980s AIDS hysteria but also refused to endorse LAGPAC’s campaign for an anti-discrimination ordinance protecting homosexuals in the city.

In 1984, Hickerson broke a color barrier when became the first black member of the queer Krewe of Amon-Ra. It’s unknown if there were hidden “passé blanc” members of Amon-Ra before, but Hickerson’s appearance made his race unquestionable. Rasmussen, present at Amon-Ra rush and initiation meetings, was instrumental in voting Hickerson into the group.

“The night I got into the organization, there were some whites who didn’t,” Hickerson recalled. As a result, several Amon-Ra members quit the organization.

Their flight is directly validated by 1984 Amon-Ra captain Mikhael Erikson, who said, “I’m sure it happened,” and partially validated by John East, a member since 1979, who recalled, “I do know there was a bit controversy; any members that were involved in that are all either deceased, moved away or no longer members.”

Regardless, Hickerson is certain that his race was the point of distress. “I was gay, so that wasn’t the issue,” said Hickerson. “I was a male, so that wasn’t the issue. The only thing that separated me from them was my skin color.” Over time, Hickerson encountered growing numbers of people trying to counter or soften his memories. “People like to remember it their way, that it didn’t happen,” insisted Hickerson. “But it did.”

Buddy Rasmussen reigned as queen of the 1985 Amon-Ra ball with full drag pageantry. Curtains opened, and he emerged in a scepter and crown and sequined gown attached to colossal butterfly wings that expanded the width of an auditorium stage riser.

But though he held a coveted ceremonial role that year, with every reason to bask in his moment, Rasmussen helped Hickerson achieve notoriety with a costume based around the tableaux theme of Cherries Jubilee, the popular desert.

As Cherries Jubilee, wearing a veritable set piece made from an inverted child’s baby pool covered in white foam and red rubber dots, Hickerson made his Amon-Ra ball premiere and won several coveted Mardi Gras costume awards. “He was stunning in drag,” recalled John East. “He looked like Diana Ross.”

Afterwards, discriminatory door policies couldn’t keep men like Downing or Hickerson or Mitchell out of the Bourbon Street gay scene. “I was dancing on the bar by then,” Hickerson said. More black gay bars flourished at a remove from the Bourbon Street strip like Wolfendales on Rampart Street.

Hickerson served as Grand Marshall of the 1985 gay Southern Decadence parade and became the veritable toast of the French Quarter with his memorable nickname Fish (a reference to a then-common term for Black women now known to be misogynistic). “There were black queens who were welcome in every circle and every door no matter where they went, and ‘Fish’ was one of them,” recalled David Williams. “Rusty Downing, too. But the general black population, less so.”

Negative terminology for black gays still did circulate among white gays, especially when black gays weren’t present. “White queens, trashy white queens would still use the N-word,” recalled David Williams. “Commonplace. But ‘dinge’ was old by then, negative. You figure out the irony there.”

Harder to pin-down racial quotas replaced discriminatory door policies at gay bars, which kept overall bar crowds from getting what owners still reckoned as being “too black” or, as Rusty Downing described hearing the terminology, “too ethnic looking.”

To add complexity, many of the doormen enforcing these quotas were non-white themselves. To avoid blowback, gay bars like Le Bistro hosted the occasional three-for-one drink night (informally called “Black Night”), where quotas went out the window, and black gays ruled Bourbon Street for an evening.

In 1990, Larry Bagneris ran for New Orleans City Council. He beat 16 other candidates to force a run-off election for the District C seat, which he lost. Had he won, he would have become New Orleans’ first openly gay elected official. Instead, in 1999, he received appointment as executive director of the New Orleans Human Relations Commission, overseeing all civil rights matters citywide.

By 2004, Hickerson achieved enough clout to become the first black queen of Amon-Ra in the organization’s 39-year history. Exhausted, yet satisfied that he made his mark, he quit soon afterwards. This year, Gabriel Mitchell followed Hickerson’s lead as queen of Amon-Ra for Mardi Gras 2019. “I wasn’t sure if I was the first black queen or if we’d had other ones before,” said Mitchell, a third-year member central to the krewe’s future plans but still learning its lineage.

When Mitchell emerged on stage in a pink and purple gown with a radiating tail of peacock feathers, a sea of flashbulbs illuminated his smile, but his parents were not in the crowd. Mitchell’s sexuality, much less his participation in drag pageantry, remains a delicate subject. “I actually didn’t give them an invite because I didn’t want there to be any drama,” said Mitchell. “And I also think I didn’t want the rejection.”

As the first-born son of a religious household from Sulphur, LA, Mitchell, at 34 years old, continues to be subject to “biblical expectations” imposed by family members, who otherwise love and defend him fiercely. “My dad still harbors this idea that maybe one day I can get married and give him a grandchild like my two younger brothers, who’ve both had children,” he explained. “I think that’s probably his one dream, the one thing he maybe never gets.”

A part of Mitchell believes that he missed out by not having his parents share in his crowning moment, but he hasn’t decided if he’s going to invite them to the ball next year.

Similarly, queer teenagers of color throughout New Orleans often remain hedged in by religious or cultural conventions that do not affect their white gay peers.

For example, Ben Zervigon, who at 18 years old is the youngest member of the gay Krewe of Armeinius, stands on the vanguard of queerness as a white high school senior—out to his family and greater New Orleans. (Full disclosure: my husband Ryan Leitner has been a member of Armeinius since October 2018.)

“I’ve been quietly thankful many times to be in the family I’m in,” wrote Zervigon in a recent Facebook direct message. But he cannot ignore the disparities made apparent by his openness. Several of Zervigon’s close friends are Black teens who plan to be closeted until college due to religious pressures.

“Many don’t face physical violence of any kind but do face [the prospect of] being blacklisted by the community and disowned by their families,” he explained. Zervigon feels that it will take more generations to eradicate such uneven progress.

‘Their goal was to locate LeBlanc’s remains in the remote potter’s field’

Recently, the City of New Orleans’ stance towards the UpStairs Lounge legacy has advanced from arm’s-length to a more open embrace. In June 2018, at a memorial observance for the 45th anniversary of the tragedy, LaToya Cantrell, the first black female mayor in New Orleans history, walked down the center aisle of a French Quarter church and recognized the UpStairs Lounge as part of the city’s story.

Since that time, Mayor Cantrell’s office commissioned a task force to work with the family of UpStairs Lounge victim Ferris LeBlanc. Their goal was to locate LeBlanc’s remains in the remote potter’s field called Resthaven Cemetery, where he was buried alongside the three unidentified fire victims, and help the family bring him home to California.

“Our office convened a small team and they have been working hard to help the family get answers and pursue multiple lines of inquiry in the search for their loved one,” wrote Vincenzo Pasquantonio, director of the New Orleans Office of Human Rights and Equity, in a recent email.

“At this time, we have exhausted our current avenues. We remain actively engaged and ready to bring all available resources to bear if new information presents itself.”

Several candidates for the unidentified fire victims, such as Larry Frost and Reginald Tubbs, have emerged through recent scholarship. Unfortunately, at present, cemetery records lost in intervening decades hamper the ability to exhume LeBlanc’s body from his unmarked plot or to compare any unidentified remains with DNA from potential families seeking closure.

The Louisiana State Fire Marshal’s Office, likewise, stepped forward to recognize the 1973 fire as part of their agency’s history.

Trevor Santos, a senior deputy fire marshal who is also the first openly gay officer to serve in his state department, reexamined the UpStairs Lounge investigation in recent years and found neither bias nor negligence on the part of his former colleagues, who doggedly pursued leads until the case closed in 1980.

Yet, the legacy of a black gay bar like the Safari Lounge closing mere days after the fire remains unexplored. All records concerning the fire inspections that followed the notorious arson were lost to Hurricane Katrina in 2005, according to New Orleans Fire Department spokesperson Captain Edwin Holmes.

When asked for comment on past actions against the Safari Lounge or how the NOFD would respond to a similar situation today, Fire Superintendent Timothy McConnell stated, “The New Orleans Fire Department is a very professional and progressive organization that takes pride in being representative of and respectful of every member of our community. The NOFD does not discriminate on any basis [sic] and no current member would be able to comment on the alleged actions of department representatives from over forty-five years ago.”

Cultural tensions and insensitivities leveled at black gays in New Orleans persist into the present day. “To this day, I can hardly remember the last time I saw a black gay couple in the Quarter holding hands,” said Howard Philips Smith, author of Unveiling the Muse: The Lost History of Gay Carnival in New Orleans. “It’s almost always a biracial couple.”

Terms like “snow queen” still reportedly circulate among local black gays as a holdover of the racial tensions of previous decades. “I’ve heard ‘snow queen’ as late as the last five years,” said Ken Mitchell. “I don’t really consider it to be out of use.”

It’s widely debated if “passé blanc” is still a racially appropriate term, as it’s capable of pitting black folk against black folk with its loaded meanings, but it continues to be spoken around town.

No books, to date, have been written about the black gay history of New Orleans. “There’s nothing that’s written from the black perspective,” agreed Hickerson. “I mean, there were more people besides me who could have told you this stuff, but they’re gone. It wasn’t important then. We weren’t important.”

So many voices, all sources note, were lost to AIDS or violence or Hurricane Katrina or natural causes. Only one bar catering to black gay patrons, The Page on Rampart Street, remains open for business.

Back in 1985, Hickerson didn’t know if Cherries Jubilee was going to make its Mardi Gras ball premiere. He and Buddy Rasmussen had spent months sewing and constructing the costume inside the Amon-Ra krewe den.

But when it came time to move Cherries Jubilee out of the den’s front doors, the oversized costume got wedged.

Someone yelled that Hickerson would have to saw off pieces and reassemble them at the venue.

“I remember Buddy Rasmussen taking the double doors off of the clubhouse den to get my costume out,” said Hickerson. “Rather than deconstruct my costume, he took the doors off.”

The moment transformed into a powerful symbol. One of the oldest gay organizations of the city was opening its doors a little wider to embrace a radical new member.

That such a gesture had come from an UpStairs Lounge survivor and Black ally like Buddy Rasmussen, for Hickerson, showed that the era of “dinge” and the “dinge queen” in New Orleans was drawing to a close.