The uplifting story of how baseball saved Alex Postma and the infuriating story of how it sent him crashing again

In November, a couple months after his last crash, Alex Postma told his father, Mike, that he wanted to start playing baseball again. For the previous three years, as his life vacillated between crashes and the fallout from them, he rarely picked up a ball. Mike asked what was different this time. Alex said he was ready.

When Alex crashes, he sequesters himself in his room and doesn’t leave. He used to hide under the bed or in a closet. Now 17, Alex simply sleeps more than half the day. The anxiety strangles him. The depression envelopes him. Fatigue, stress, illness – they all precipitate the crashes. He has tried therapy and medication. Nothing works. Once a crash starts, it is a runaway train. “I just want to be normal,” he often tells his mother, Julie, and Mike. “I just want to be normal.” Mike and Julie always tell him he is.

Mike – an educator who specializes in helping twice-exceptional kids like Alex, who are gifted but also have special needs – calls the episodes “crashes” to illustrate how visceral they are. “When he’s in those funks, he becomes non-verbal, almost non-functional,” Mike said. “We struggle to get him out of his bedroom. Mental illness is so stigmatized, but it’s real, and people just don’t seem to understand it shuts you down.”

It’s what made Alex’s request in November so out of character. Going out for the baseball team at Topsail High School in Hampstead, North Carolina, a coastal town about 100 miles north of Myrtle Beach, would force him to spend every afternoon around kids he barely knew. Even though Alex was a senior, most of his high school education took place at home. He would attend school for a few weeks, crash and spend the rest of the year on a homebound curriculum, taking the school’s courses from his house.

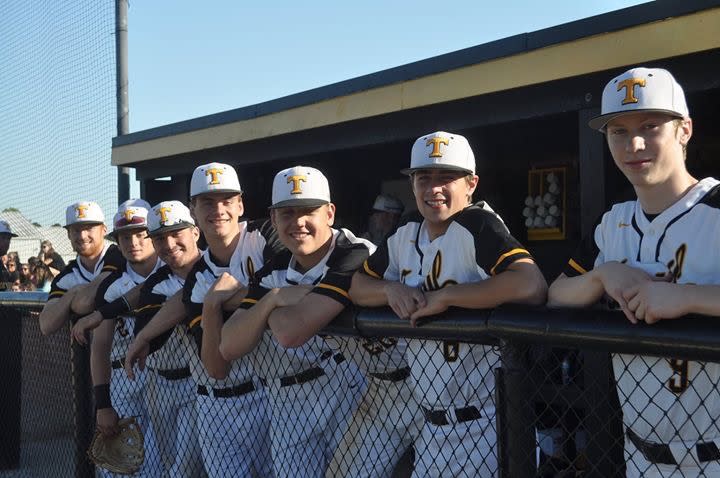

Alex started training six days a week and attending optional workouts for the baseball team. At 6-foot-2, 170 pounds, he was a phenomenal athlete. He started dunking a basketball as a ninth grader. When he did a standing backflip at the gym during the baseball workouts, the coaching staff wondered who the kid was. He was no charity case. He earned his spot on the Topsail varsity team and served as a pinch runner for the catcher, who under state rules could be replaced every time he got on base. Topsail was one of the best 3A teams in North Carolina. Things went so well with the baseball team, Alex had gone back to school without crashing.

“The baseball field is his domain, his place of solace and comfort,” Mike said. “That was his place he felt normal.”

The investigation

This should be an uplifting story about the gift of baseball, the power of acceptance, the way a team and community rallied around a boy – and it is. This is also a story of small-town infighting, of a dubious investigation and opaque second investigation, of a governing body struggling to reconcile the letter of the law with its spirit – and of that same boy who today languishes in his room and sleeps away most of the day, the entirety of it all sending him crashing again.

May 1 was Senior Day at Topsail. The Pirates were cruising to another playoff berth, and Alex, wearing his No. 9 jersey, walked arm in arm with his mother as the rest of the team clapped and celebrated the seniors. Julie beamed. All the years, all the struggles, all the moments where she simply wished Alex could be happy. Finally, he was.

Alex did not realize he was the topic of another conversation that day, too. Berry Simmons, the principal of Topsail, later told parents that he had been informed of a possible eligibility issue with Alex that Tuesday. (He still has yet to indicate to parents or publicly where he received the information.) The next day, Simmons called Aaron Rimer, Topsail’s baseball coach, and warned him of the potential problem. On Thursday, the Pirates played their final regular-season game – without Alex in uniform. Simmons pulled the baseball team out of class Friday and gathered it in the auditorium to deliver the news: Topsail would be self-reporting an eligibility violation and forfeiting every game except the final one. The Pirates would officially be 1-22 instead of 16-7. They would not play in the postseason.

When Alex crashed in September, he tried to transition to an online offering of the homebound program. Even with his struggles, his transcript mostly showed A’s and B’s, though his fall semester’s course load was heavy even for him: AP Calculus, another AP science course, advanced history and Spanish. He fell behind in his transition online and wound up pushing Spanish to the spring semester and trying to take an incomplete in calc. That left him with two courses passed.

To stay eligible for high school athletics in North Carolina, a student must pass at least three classes the previous semester. The responsibility for determining eligibility in North Carolina falls on the principal, Simmons, and athletic director Barry West. Why they didn’t red-flag Alex and petition the North Carolina High School Athletic Association for a hardship waiver is unclear. The waiver could have granted Alex eligibility and salvaged Topsail’s season.

Simmons told parents of Topsail baseball players that the school conducted a thorough investigation into Alex’s eligibility – a claim the parents find specious and dubious. They gathered en masse at the most recent school board meeting to bemoan the lack of transparency from the district and administration.

“There was zero communication from school and district officials, which leaves everyone to wonder if a cover-up is happening,” said Shayne Frey, the father of one player. “Who did that investigation? Did the administrators who failed to do their job investigate themselves?”

The anger over the initial investigation and the decision to self-report the violation prompted the county school district to open its own investigation. West, the Topsail athletic director, did not return messages seeking comment. He resigned Wednesday night, telling the crowd at a banquet for the lacrosse team that the job no longer was fun, according to the Wilmington Star-News.

Simmons, the principal, wrote in an email to Yahoo Sports: “I appreciate the opportunity, but I cannot speak with anyone or release any information until our superintendent, Dr. Steven Hill, completes his investigation.” Miranda Ferguson, a spokesman for the district, said in an email: “Pender County Schools is investigating this matter. In order to preserve the integrity of the ongoing investigation, the district will not discuss it. By law, the school system cannot discuss student or personnel matters but we are actively working on what we hope will be a beneficial resolution.” When asked whether the closure of the original investigation allowed those involved to address it, Ferguson did not respond.

“They feel like the parents are going to stop and this is all going to go away,” said Julie Cota, whose son, Miles, was a junior on the baseball team this year. “We’re not, and it’s not.”

Cota and others at Topsail are tired of the turnover that plagues the school in spite of success that includes a state championship and three final fours in recent years. Rimer, in his second season, is the sixth baseball coach over the last eight years – and parents told Yahoo Sports that Simmons encouraged Rimer to quit multiple times this year. Rimer declined to address the allegation, preferring, he said, to focus on Alex because he was the real story of the season.

And Rimer is right. Once Alex backflipped into everyone’s consciousness, the team tried, slowly, to draw him out. They called him Lightning – short for White Lightning, a name he first got, his father said, when he dunked as a freshman. While Rimer’s rules called for no headphones during practice, he made an exception for Lightning. Same thing went when Alex crashed during tryouts. Rimer had seen him come back from three years off; Alex made the team without a single tryout, another of the more than 100,000 kids from 413 schools to compete in high school athletics annually in North Carolina.

Only 10 to 15 a year lose their eligibility.

“We want everyone to be eligible,” said Que Tucker, the NCHSAA commissioner. “We’re just selfish enough and egotistical enough to believe that everyone can glean so much by being part of athletic programs. We don’t look for ineligibles.”

When ineligibles find them, Tucker endeavors to balance fairness, compassion and fidelity to the rules. She knows Alex’s story. She sees him as the embodiment of the association’s selfishness and egotism: High school sports really can change lives. At the same time, she understands that this would not be some ruling in a vacuum – that ruling Alex eligible would have constituted opening a Pandora’s box.

“If you miss it in January and then you find out in May and you want to make it retroactive, we can’t do that,” Tucker said. “Because then we would start to govern in a discriminatory fashion. There has to be some measure of consistency by which we apply the rules. We believe our schools are very, very intent on making sure all students have every opportunity to participate. But every now and then, a school will miss a student.”

Topsail missed Alex, the most obvious student of all, and it meant seven seniors – two going to play Division I baseball, two going to Division II, one going into the military, one going to college to become an engineer and Alex – would miss their final shot at a state title.

He would have been the easiest scapegoat imaginable, too, the kid who shouldn’t have been there in the first place. Nobody blamed Alex. Not his teammates. Not their parents. Not the coaches. No one. He reminded them why they love baseball: because if it could coax a kid who spent so much of his life in a dark place out into the light, imagine the regenerative properties it could offer for anyone.

“The whole team has reached out to him, texted him, saying we all still love him,” Topsail catcher Colby Emmertz said. “We were glad to have him on the team. We’d do it again in a heartbeat.”

The aftermath

They try to pass along messages or words of encouragement or whatever might persuade Alex that none of this is his fault. They’re just kids, too, and that’s the worst part of it – that with the accusations, the speculation, the confusion, they feel like pawns in some sort of stupid adult game. They just want to go back to playing baseball and Fortnite and doing fun stuff like a charity Halloween game in costumes against the Topsail girls’ softball team that raised more than $3,000 for a local homeless shelter.

One Topsail baseball tradition is for the boys to wear their tuxedos for prom to the field and do a black-tie photo shoot. Alex’s teammates invited him. He still wasn’t ready.

“Deep down,” Mike said, “he still feels responsible.”

And that is such a crushing feeling, one that triggers the anxiety and depression and sends Alex crashing – one that if it really were the product of someone trying to further a petty feud would be beyond heinous.

“I don’t think people understand what non-verbal means,” Mike said. “When he’s down like this, he doesn’t just internalize it. He won’t express himself in any form or fashion. It’s scary. It’s really scary.”

They’re trying to focus Alex on his immediate task at hand: graduating on time. He’s got a few weeks to climb out of the abyss, finish his schoolwork and ready himself for whatever is next. And what that is he’s not quite sure. He loves baseball, enough that he was evaluated by Fletcher Bates, a former minor league player who runs Rock Solid Baseball, a local travel team. Alex has the physical tools to join the travel circuit, Bates said, and maybe even play some college ball. He just needs polish – the sort he could have gotten over the last month.

Instead, Topsail is at home, watching New Hanover High School advance to the 3A state semifinals. What really gets the players is New Hanover’s record: 25-0, as if the two times Topsail actually beat New Hanover this season never existed. It’s injury to insult.

Much as Alex took solace in baseball, in an odd way, his teammates and his community take it in him – in knowing that they could lift him up once, in trying to do it again, in hoping the glint they saw in his eyes when he was playing the game is not some fleeting feeling but a new normal.

“If someone came to watch our game, nobody could tell he was different than any of us,” Emmertz said. “He was a baseball player. Just one of us.”

More from Yahoo Sports:

• Trump: Maybe NFL protesters ‘shouldn’t be in the country’

• Charles Robinson: What did the NFL hope to gain from Kaepernick poll?

• Footage of Bucks player’s arrest released

• Terez Paylor: NFL players react to league’s new anthem policy