Under Armour’s sneaker problems, explained by one metric

On Tuesday, Under Armour reported a big miss on its 2016 Q4 earnings, and its stock plummeted 25% in response. But among the numbers were some bright spots, including footwear. Under Armour said its footwear revenue grew 36% in the quarter.

But NPD Group, which tracks retail data and is a leading source of sneaker industry research, says Under Armour footwear sales declined 20% in the quarter.

How do you reconcile those two numbers? The answer involves the difference between wholesale and retail.

Under Armour’s number combines both—what Under Armour sold to retailers in bulk, and what actually sold to consumers at its own retail stores. NPD Group, which focuses on retail, is only measuring what gets sold at stores, one pair at a time. And that’s the more telling number.

The disparity between wholesale and retail in this case shows that Under Armour sneakers slowed down at retail stores, and inventory built up—in other words, retailers were left with Under Armour shoes that didn’t sell. That will likely slow down sales in the near future as well.

Make no mistake: Under Armour isn’t fudging the numbers. These companies are required by the SEC to report product sales in a two-system manner. But the 36% growth number is still misleading. It suggests Under Armour’s footwear business is healthy, when it isn’t.

Retail is the simple, straightforward metric most consumers care about and think about. It answers the question: How many shoes did Under Armour sell to shoppers? And retail sales are what most of the industry cares about too, as opposed to shareholders, who just see that footwear grew, which looks positive. NPD Group analyst Matt Powell explains, “I think you can look at retail as a bellwether for whether or not a brand is doing great.”

In a converse example, Adidas retail sales nearly doubled in the second half 2016, but its wholesale numbers will not be up for the year, Powell says. That’s because their shoes are selling out at retail. As Powell says, “You sell in in pallets, and you sell out in pairs.”

It’s worth mentioning that Under Armour’s own retail business (official brand stores) has done well despite the slowdown of the past year. But Under Armour sold too much product to retailers going into the holidays, and that product did not sell out at stores as expected.

The liquidation of major sports retail brick-and-mortar chains in 2016 killed Under Armour—especially that of Vestis Group, which owned Sports Authority and Sports Chalet.

Those stores represented 20 million square feet of retail that closed in one fell swoop. That was 10% of all the sporting goods retail space in the US. “We’ve never had such a dramatic decline in square footage so quickly,” says Powell.

That hurt brands that over-indexed at Sports Authority, like Under Armour and Nike. Adidas, as it happens, did not have a large business at Sports Authority. Under Armour CEO Kevin Plank called out the brick-and-mortar death march on the earnings call: “While it’s certainly not news,” he said, the bankruptcies “disrupted the North American retail landscape.”

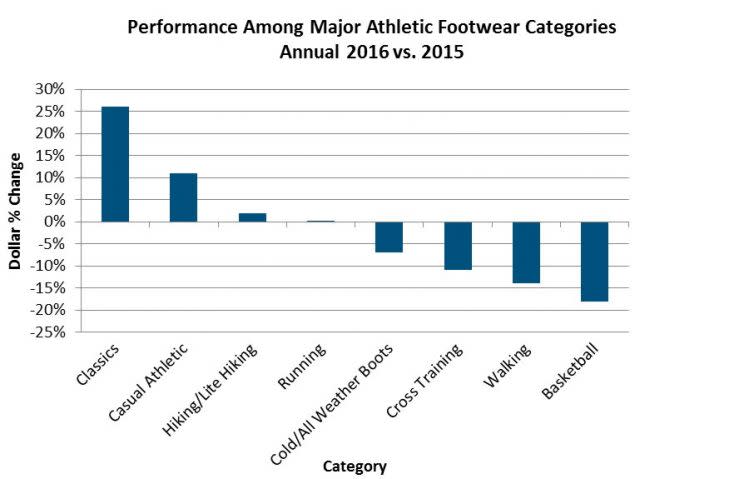

In addition, overall sales of “performance” basketball shoes (that is, basketball shoes made for playing basketball, as opposed to fashionable, so-called inspired-by basketball shoes) fell nearly 20% in 2016. (See the above chart from NPD Group.) That particularly hurt Under Armour and Nike.

Under Armour has placed great emphasis on its line of Stephen Curry signature basketball shoes—last April, on its 2016 first-quarter earnings call, Plank could not stop praising Curry—and now those shoes have cooled off.

@siredwardnigma see–Curry sold great until the fashion shift caught up

— Matt Powell (@NPDMattPowell) January 31, 2017

Across the board in sports retail, fashion has become a focus. The so-called “classics” category was the No. 1 driver of athletic footwear sales last year, NPD Group says.

That’s why Adidas, with its Originals segment, thrived. Nike and Puma can also “leverage that trend well,” says Powell. Under Armour, which has only been around 20 years, “doesn’t have a retro business to resurrect and bring back. So they can’t play there.”

—

Daniel Roberts is a writer at Yahoo Finance, covering sports business, media and technology. Follow him on Twitter at @readDanwrite.

Read more:

Under Armour: We have to be a premium full-price brand

Under Armour is on an athlete endorsement deal hot-streak

Adidas calls Under Armour’s athletes ‘milquetoast’

Under Armour CEO Kevin Plank gets into the ‘sippin’ whiskey’ business