U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Alabama redistricting case could affect Florida’s map

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

A U.S. Supreme Court decision striking down Alabama’s congressional districts map could have implications for Florida’s ongoing battle over Gov. Ron DeSantis’ 2022 redistricting plan.

The court’s 5-4 decision, which was released Thursday, affirmed a lower court’s ruling that Alabama violated the federal Voting Rights Act in drawing a map that had only one majority Black district in a state where more than 1 in 4 residents are Black. The ruling confirmed that race could be used when looking at redistricting.

Thursday’s decision could impact ongoing redistricting challenges under the Voting Rights Act in states like Louisiana and Georgia, experts say.

The legal situation with Florida’s congressional map is slightly different. The Supreme Court ruling isn’t a clear win for voting rights advocates challenging the Sunshine State’s map, say people who study redistricting, but is still likely unwelcome news for DeSantis as he pushes the idea that Florida maps should be drawn in a race-neutral way.

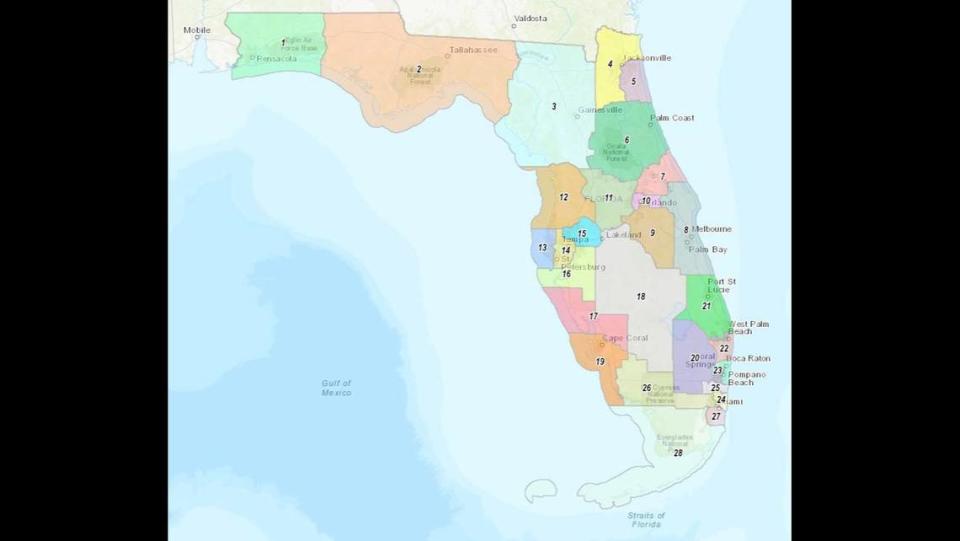

After DeSantis vetoed state legislators’ original map of congressional districts, the Legislature in 2022 approved a map proposed by the governor that more heavily favored Republicans and dismantled a North Florida congressional district previously held by a Black Democrat, Al Lawson.

Florida voting advocates said the state’s maps unfairly put Black voters and their candidates at a disadvantage. But unlike in Alabama, where plaintiffs said the maps violated the federal Voting Rights Act, a state lawsuit in Florida focuses on whether the maps violate the state Constitution’s Fair Districts Amendment. (A separate lawsuit brought by other voting rights groups challenging Florida’s maps in federal court also does not focus on the Voting Rights Act.)

The Fair Districts amendment was adopted by voters in 2010. It says that districts should not be drawn with the intent or result of denying racial minorities the ability to elect candidates of their choice. But DeSantis said he wanted to design the congressional map in a “race neutral” way, saying he believes the Fair Districts requirements are unconstitutional.

(On Monday, a judge ruled that DeSantis’ administration is allowed to argue in trial that the Fair Districts requirements violate the equal protection clause of the U.S. Constitution.)

Matthew Isbell, a Democratic data consultant and redistricting expert, said the U.S Supreme Court’s ruling isn’t a “magic bullet” for the ongoing challenge in Florida but said it “definitely isn’t what the DeSantis side would want to see.”

“What it’s signaling to the courts, the Florida courts that are going to be hearing this case, is that race is still a legitimate factor to be considered in redistricting,” Isbell said.

In the Supreme Court case, Alabama’s attorneys argued that the court should adopt a “colorblind” interpretation and avoid taking race into account. The court rejected that.

Michael McDonald, a University of Florida professor who studies redistricting, said if the Supreme Court had weakened the Voting Rights Act in its ruling as many anticipated, it would have given the state a stronger leg to stand on when arguing that Fair Districts requirements violate federal law.

McDonald said the arguments Alabama was making about the Voting Rights Act parallel the arguments DeSantis has made against Fair Districts.

Though McDonald said the Supreme Court’s ruling weakens the state’s argument, he said “it may be yet that the Florida Supreme Court will find other reasons and rationales” to side with the state. He said Thursday’s ruling doesn’t grant Florida voting advocates an automatic win “by any stretch of the imagination.”

The North Florida district previously held by Lawson stretched from Gadsden County to Jacksonville. About 46% of the voters in the previous district were Black. Had it been 50% or more, it would have met the starting criteria for a Voting Rights Act challenge, McDonald said.

Kareem Crayton, the senior director of voting rights and representation at the Brennan Center for Justice, said it’s hard to apply the ruling on one law to another law. Typically the state Supreme Court would be final arbiter on state law.

But, he said, even though Florida’s challenge isn’t under the Voting Rights Act, the plaintiffs could still pull from applicable parts of the ruling to highlight the importance of race in redistricting.

“The statement from the court is this remains good law and it is an obligation to take account of it,” Crayton said. “And yes, sometimes that means being attentive to the likely racial effects of a map.”