In Turkey's local elections, all eyes on Erdogan

ISTANBUL (AP) — Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan has been ensnared in a corruption scandal that has toppled four Cabinet ministers. He has provoked outrage at home and abroad with an attempt to block Twitter and YouTube. His incessant us-against-them rhetoric and conspiracy theories have alienated allies. Meanwhile, the Turkish Lira has fallen, interest rates are up and the Turkish economy has fallen off a cliff.

It all might be enough to oust any leader.

But as Turks prepare to vote in local elections Sunday, Erdogan remains at the center of the political scene.

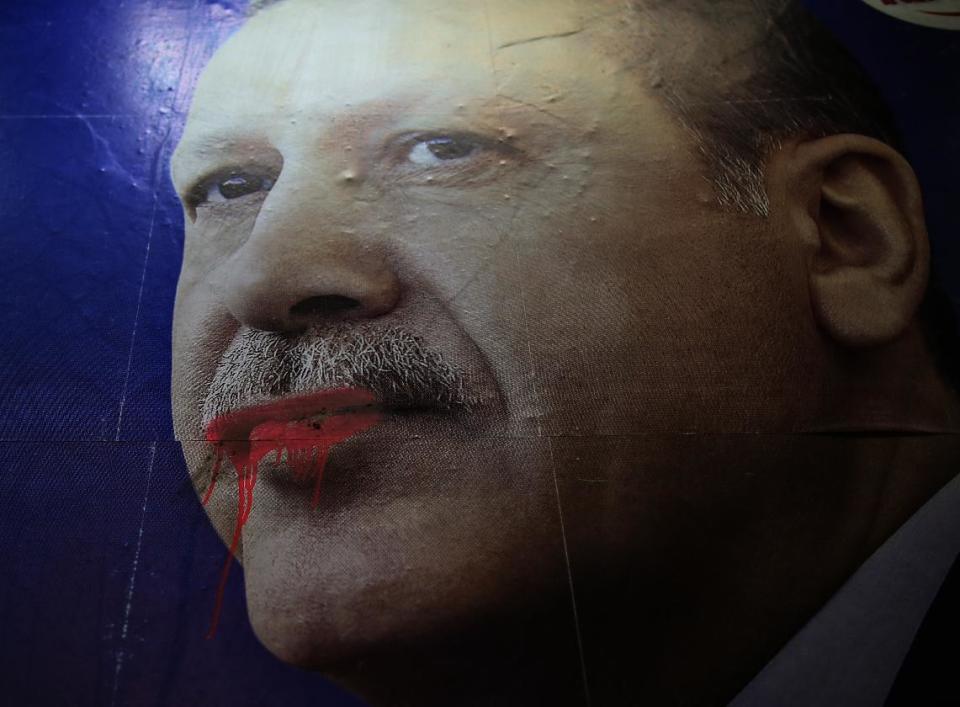

Despite his woes, Erdogan — who has presided over Turkey's astonishing economic ascent as well as its recent troubles — is Turkey's ubiquitous man. His image is everywhere in the streets and on TV. He leads daily campaign rallies, in which the local candidates he is supporting have a decisively secondary role. The size and the fervor of these rallies, which regularly attract hundreds of thousands of supporters, show that nearly 11 years into his tenure as prime minister, Erdogan remains the pre-eminent figure in Turkish politics.

Erdogan is buoyed by a dysfunctional opposition and the adulation of devout Muslim middle-classes in Turkey's heartland, who have seen him as their ticket to prosperity and who are likely to back him through thick and thin.

While there is no doubt that the corruption scandal has damaged him, the questions looming over Sunday's vote are how the results may influence his next big moves and his political options.

It remains unclear whether he'll run for president this summer. Erdogan has harbored ambitions of changing the constitution to strengthen the role of the largely ceremonial presidency — so he can step into the post and rule Turkey with as much authority as he has enjoyed as premier. He is prohibited from running again as prime minister by term limits that he himself instituted.

However, the abrasive tack he has taken since he was re-elected with nearly 50 percent of the vote in June 2011 has cost him the support of a Kurdish party that he needs to pass the constitutional changes. It's also unclear whether he could ever achieve the 50 percent of the vote required to capture the presidency.

Erdogan has signaled that he may choose another option: to backtrack on term-limits and run for a fourth term as prime minister in parliamentary elections. Those elections are slated for next year, but the government could move them up to coincide with the presidential elections, if they see that as an advantage.

Although quality polling is hard to come by in Turkey, it is widely expected that his AK Party will outstrip opposition parties Sunday, winning a plurality of the vote. But how much of a plurality will matter. Erdogan's party has already been trying to lower expectations. His party has pointed to the 39 percent they received in the 2009 local elections as a benchmark.

Races for mayor in Ankara and Istanbul will also be watched for signs that Erdogan's power base is eroding. In both cities, the main-opposition CHP has entered candidates with broader appeal than usual to take on incumbents from Erdogan's party.

Even with all of the corruption revelations, Erdogan's entrenched advantage seems to be a divided and dysfunctional opposition, whose support is spread across a number of parties. Until recently, AKP had cultivated an image of pragmatism and economic stewardship that was bolstered by a booming economy. So far the opposition has not made the case that they can make the trains run on time.

"There is a drop in the support for AKP but it is not at the level one would normally expect. In normal circumstances they would have been bulldozed to the ground," says Ali Tekin, a political analyst and former professor of political science. But he added: "Those who would like to leave the AKP can't find an alternative center-right party to go to."

Erdogan remains beloved among a core of mostly pious-Muslim supporters who praise him for opening up opportunities that they say were walled off under the rule of previous secular governments. Many dismiss the corruption scandal — which has included the leaks of alleged wiretaps of Erdogan and ministers engaged in bribe-taking and trying to cover it up. Erdogan and his allies have rejected the allegations as a plot orchestrated by followers of U.S.-based Muslim cleric Fethullah Gulen, a former Erdogan ally who has split with him.

In the Istanbul district where Erdogan grew up, it's easy to find conspiracy theorists. Yusuf Kut, a knife seller, says he has voted for Erdogan's party in every election since its founding because Erdogan has helped feed the poor.

"It's mostly nonsense," he said. "Tayyip Erdogan doesn't walk around impure, and would never swallow an ill-gotten bite."

But at Erdogan's peak, it would have been hard to find someone in the Kasimpasa district who didn't support him. These days, even his natural supporters are having doubts.

Seyma Karadag, a student who will be voting for the first time, comes from a pious family of AKP supporters in the district. She too is observant and wears a headscarf, but says that unlike her parents, she has seen enough of Erdogan's party.

She says that she finds Erdogan too divisive and is turned off by rhetoric that discriminates against minorities and foreigners.

"I don't pay attention, I don't listen to him, and I don't watch the TV channel he's on," she says.

___

Ayse Wieting contributed to this report

___

Follow Desmond Butler on Twitter at: —www.twitter.com/desmondbutler