Trump’s rivals are not trying to compete for his voters

Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump speaks during a campaign stop Friday, Feb. 19, 2016, in North Charleston, S.C. (Photo: Matt Rourke/AP)

COLUMBIA, S.C. — Donald Trump has won over many working-class Americans with his populist message, reflected in his large and consistent lead in the polls. One might expect his rivals to be targeting this large bloc of voters, but for the most part they aren’t even attempting to compete for them.

Much of Trump’s support comes from men and women who feel left behind, economically and culturally. Economically, they blame trade deals and immigration for the collapse of job markets in manufacturing and industrial towns. Culturally, they feel looked down on by elites, who live vastly different lives.

Trump, with both his policy positions and his attitude, has promised to restore the fortunes of these voters. He has said he would impose tariffs as high as 45 percent on Chinese goods that undercut U.S. manufacturers — though he’s recently tried to back away from that position — and has famously promised to deport all of the 12 million or so undocumented immigrants in the country.

It’s widely agreed upon that tariffs would eliminate American jobs of companies that export goods to China and would drive up the cost of goods for low- and middle-income Americans who shop at Walmart, Target or Amazon — major retailers that are stocked with a steady flow of cheap imports from other countries like China, where labor costs are far less for manufacturers. And in fact, manufacturing job losses over the last decade or so are due more to efficiency gains from increased use of robots than cheaper labor overseas.

Yet none of Trump’s rivals are emphasizing that point. Occasionally, one of them has said, as former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush did at a debate in mid-January, that a massive tariff would result in “higher prices for consumers” and would be “devastating for the economy.” Rubio said in that same debate, in Charleston, that “if you send a tie or a shirt made in China into the United States and an American goes to buy it at the store and there’s a tariff on it, it gets passed on in the price to the consumer.”

However, no one is focusing on this argument, either with paid ads or repeated emphasis on the campaign trail.

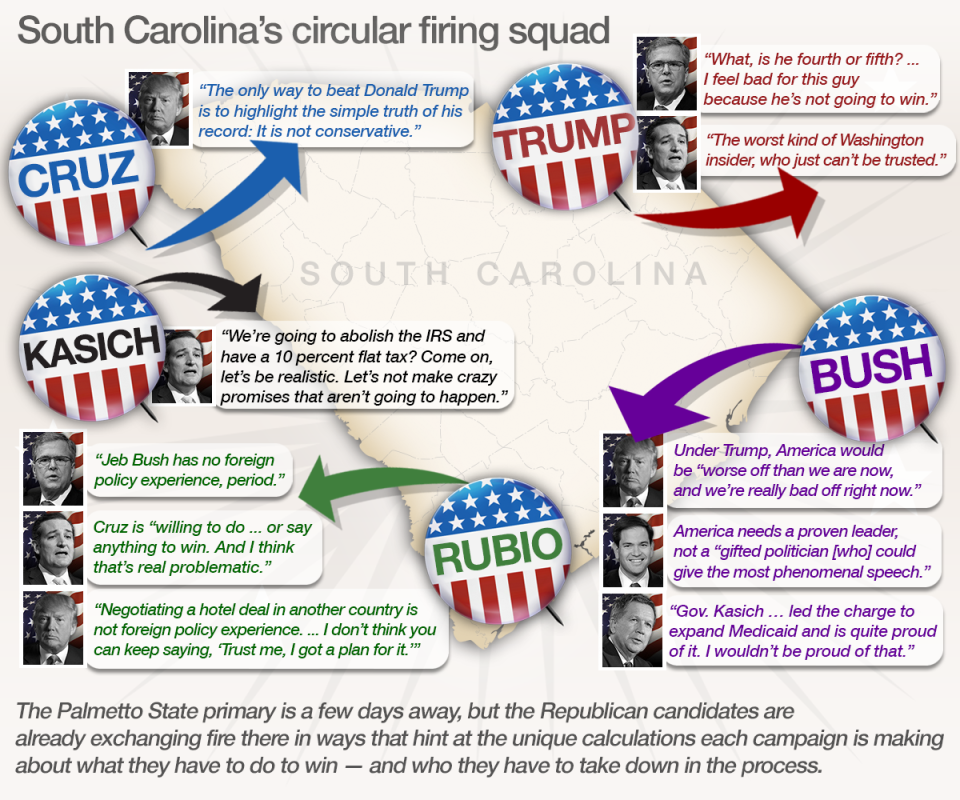

Slideshow: Republican candidates duke it out in South Carolina

Neither are they hammering Trump for saying he will make no changes to Medicare, Medicaid and Social Security, which are the biggest long-term drivers of the U.S. government’s $19 trillion national debt. If the debt continues to grow unchecked, it will hurt economic growth as well as eat up more and more of the federal budget, leaving less money for other spending.

Trade is a thorny issue. Although U.S. participation in the global economy has clearly benefitted the country as a whole over the past few decades, it has also been a period of deep disruption and loss for many Americans, whether or not it’s due to robots or cheap Chinese labor. Any argument for trade must acknowledge this, and that’s an uncomfortable proposition for a politician under the white hot lights of the presidential primary.

In addition, while Marco Rubio, Ted Cruz, Jeb Bush and John Kasich are all politicians and thus not above pandering, the idea of promising the return of manufacturing jobs en masse is too far fetched for them to promise. And so they are left with the prospect of telling bewildered blue-collar workers that the government can help them transition into a new economy.

But by ignoring the issue, they are ceding the argument to Trump. And while each of them talks with some frequency about the struggles of everyday Americans, none of them are going out of their way stylistically at events to speak directly to working-class voters and to promise dramatic action to help blue-collar and working-class Americans.

“We need to take our message to people who are living paycheck to paycheck,” Rubio said Friday at a rally in Columbia.

Presidential candidate Marco Rubio and South Carolina Gov. Nikki Haley, U.S. Rep. Trey Gowdy and U.S. Sen. Tim Scott wave as they arrive on stage during a campaign event in Columbia, S.C. (Photo: Chris Keane/Reuters)

But Rubio’s personal story — which involves his parents emigrating from Cuba — complicates any effort to reach out to voters who to some degree blame immigration for their woes. And Rubio and Cruz have been so preoccupied with selling themselves as the most dogmatically conservative that they have neglected Trump’s less ideological voters.

Avik Roy, an informal policy adviser to Rubio, said that Rubio “has spent a ton of intellectual capital on the question of how we address the problem of how the 21st century economy isn’t working for those in the lower middle class.” Roy pointed to Rubio’s “luring manufacturers back to the U.S.” and his “making vocational and higher education more affordable.”

Yet Trump’s more powerful appeal to his unique constituency may be more visceral than any policy position. Trump is someone who has lived among elites but has been laughed at by them as well, most famously at the White House Correspondents’ Association dinner in 2011, when President Obama mercilessly mocked Trump, who had been spreading doubt about Obama’s birthplace.

Trump is now running as “a traitor to his class.” He offers less-well-off Americans a chance to get back at those who they perceive to have benefitted from the same policies — free trade, open borders — that they blame for their economic plight. Working-class Americans by and large now live radically different lives than those in the upper class. Elites increasingly eat different foods than the rest of the country, have vastly different cultural tastes and have more stable families and communities.

“Another characteristic of the new upper class — and something new under the American sun — is their easy acceptance of being members of an upper class and their condescension toward ordinary Americans,” conservative scholar Charles Murray wrote recently. “Mainstream America is fully aware of this condescension and contempt and is understandably irritated by it.”

Trump, who has mastered the process of manipulating the entertainment- and outrage-obsessed worlds of TV and social media, is acting out his own revenge on those who have scorned and mocked him.

“A lot of people have laughed at me over the years,” Trump said last month. “But they’re not laughing at me anymore.”

Tech entrepreneur and marketing genius Seth Godin inadvertently explained the way that Trump supporters can live vicariously through their hero. In a recent interview, Godin explained the difference between companies like Suzuki and Harley Davidson.

Suzuki makes cars for people to buy “if all you want is transport,” Godin said. But “no one gets a Suzuki tattoo.” By contrast, motorcycle maker Harley Davidson is a tattooworthy brand, because it does something more than just sell a product.

Harley Davidson, Godin said, “changed disrespected, disconnected outsiders into respected family members, insiders.” It is a company started by people who said, “The purpose of my business is to change people, to change them from something into something else.”

“That’s what you get when you pay $12,000 for a motorcycle,” Godin said.

Translated into this year’s presidential race, Harley Davidson represents Trump. Suzuki, run by people who apply “systems thinking to an existing clear need,” is a symbol for a candidate like Bush.

Bush, the former Florida governor, is a “systems thinker.” During a recent town hall meeting in New Hampshire, Bush had several chances to connect on a personal level with people in the audience who asked questions: a student, a woman with a sick father and a blue-collar man who asked about jobs lost to outsourcing.

In each case, Bush missed his window to make a personal connection and retreated into talking about wonkish policy details and big picture analysis of the problem. Though Bush did show some emotion when he began to talk about his daughter’s struggles with drug addiction, even then he quickly suppressed his feelings and moved quickly to a discussion of how to best help addicts.

The man who asked Bush about jobs lost to other countries looked more blue collar than most every other person inside the packed school cafeteria, who by and large looked like the well-to-do voters who usually attended 2012 Republican nominee Mitt Romney’s events. His head was shaved bald and he had a handlebar mustache that prompted Bush to call him “the man with the cool mustache.”

The man asked Bush: “What’s your plan for bringing jobs back that have left: Ford, GM, other companies, manufacturing. What’s your plan to get those companies back here to create a better job base?”

Bush could have noted that many blue-collar Americans feel that the political elite have sold them out through free trade deals and badly enforced borders and thanked the man for coming. He could have asked him about his personal experience and drawn out his feelings about Trump.

Instead, Bush went straight to tax policy, arguing for a change in how the U.S. government taxes companies who bring profits back home from plants or offices overseas.

Bush could sense that his talk of a “territorial tax system” was not connecting. “Capital investing may sound like an abstract idea,” he said.

Yet he persisted with the clinical argument. “It’s how you create higher wages,” he said.

That may be, but voters want more than dry theory or even facts. They want a human, emotional appeal as well. And on both counts, Trump’s rivals are surrendering a large swatch of the electorate to the current frontrunner.