Trump, honoring Holocaust survivors, seems blind to events of today

In the first half of his State of the Union address Tuesday night, President Trump warned of the swarms of “criminal illegal aliens” massing at the southern border, threatening to bring gang warfare and sex trafficking and illegal drugs into the United States.

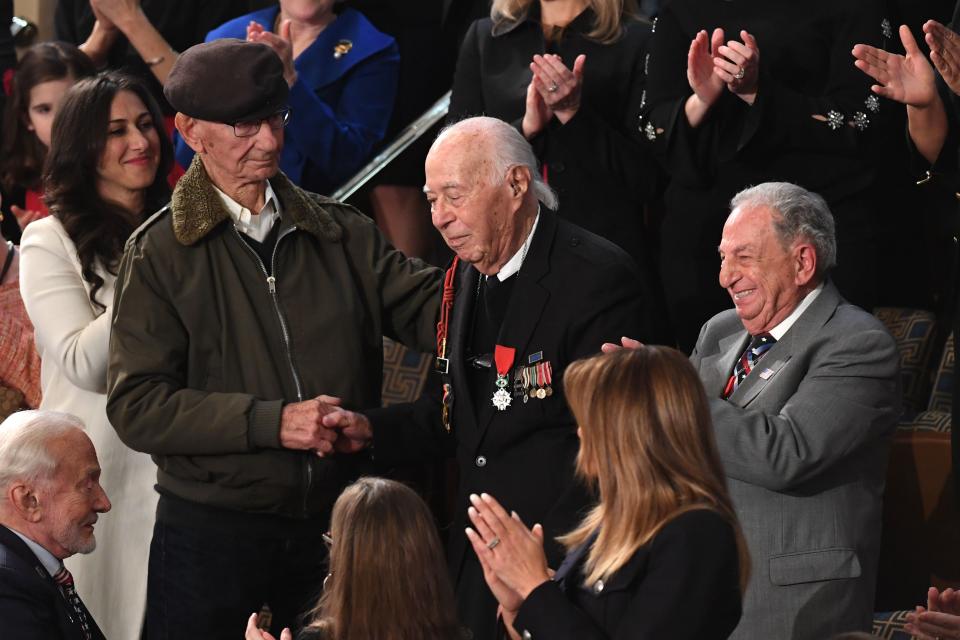

Later in the speech he introduced two Holocaust survivors who had been liberated from Nazi death camps by American soldiers, likening their rescuers to angels coming “down from heaven” and their subsequent life in America as “proof that God exists.”

What he didn’t say is that thousands of Jews who died in the Holocaust could have been saved if an earlier president, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, had allowed them into the country when they tried to flee Germany before World War II. Or that the “criminal illegal aliens” he is demonizing are in a similar situation to those German Jews, seeking refuge from oppression and violence at the hands of gangs that rule many towns in Central America.

“On the one hand he celebrates the liberators, some of whom were immigrants, and the liberated, who became immigrants,” said Deborah Lipstadt, a professor of Jewish history at Emory University and author of “Antisemitism Here and Now,” which was published this week. “On the other hand he vilifies the people today who are here to become immigrants. Those immigrants are the same as these immigrants, but some are terrifying and the others are heroes in the same speech. The mind spins.”

In the decade before Herman Zeitchik (the soldier Trump honored last night) had liberated Dachau, saving Joshua Kaufman (whom Trump also honored), hundreds of thousands of German Jews applied for entry to the United States.

America had no refugee policy at the time. Those fleeing persecution had to apply through the same channels as those immigrating for any other reasons, and had to meet the same rigorous requirements. This included extensive documentation of their identity, finances and medical history.

Moreover, they were subject to tight quotas that had been passed by Congress in 1924, when Americans began to fear that too many Catholics, Jews and dark-skinned non-Anglo Saxons were arriving on their shores. Under that law only 153,774 immigrants were permitted into the country annually, compared with nearly 1.3 million in the peak year of 1907. More than half of those slots were reserved for people from Great Britain and Northern Ireland, based on a formula that attempted to preserve the ethnic balance of the population in the 19th century. During the Great Depression the quotas became stricter still, amid concerns that newcomers would take jobs from those who were already here. This led to a tightening of the enforcement of a prohibition on immigrants “likely to become a public charge,” meaning applicants had to prove they could financially support themselves.

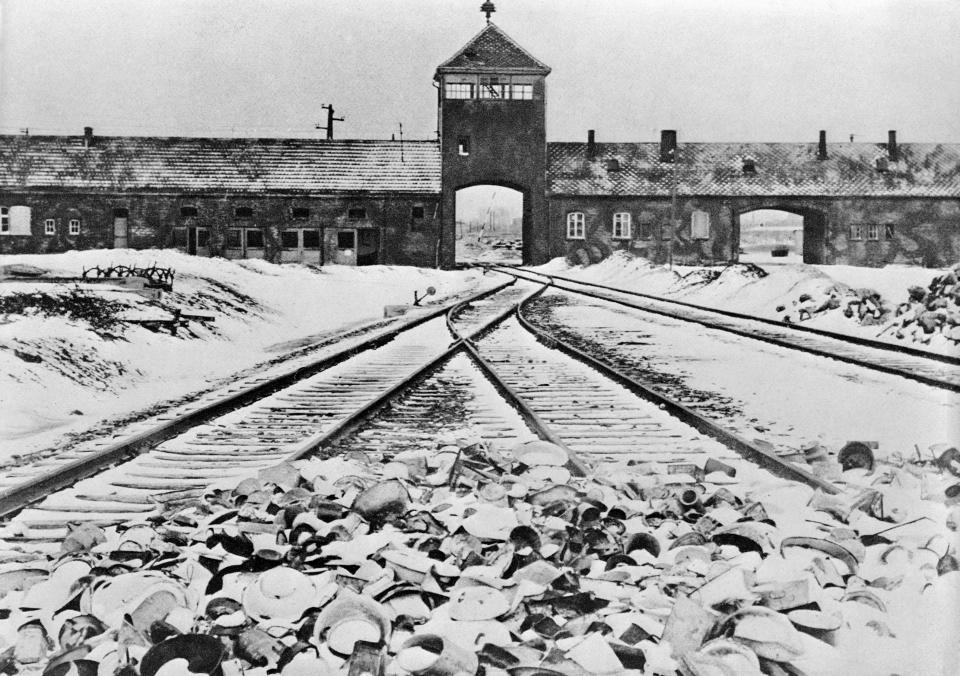

As Hitler seized property and tightened employment prohibitions on German Jews, they were increasingly less able to provide the required proof. Because so many applications were rejected for economic reasons, only 20 percent of the visas theoretically available to Germans under the quota were issued during FDR’s first term — akin to the Titanic lifeboats being lowered less than half full. Wait times for applications to be processed grew to 10 years. By 1938 there were 125,000 applications from Germans and Austrians (by that time Austria was under German occupation), but the combined quota for those countries was 27,000.

That was the year of Kristallnacht, when Nazi mobs attacked German Jews on the streets and in their businesses. The next year, 937 (mostly Jewish) passengers attempted to flee Europe aboard the MS St. Louis, which was bound for Cuba, but was not allowed to land. On Roosevelt’s orders it was also denied permission to dock in the United States. As it sailed in circles in Miami Harbor, hoping for word that quotas had been relaxed, a telegram arrived from the State Department saying “[Passengers must] await their turns on the waiting list and qualify for and obtain immigration visas before they may be admissible into the United States.”

The ship eventually returned to Europe and disembarked the passengers. Historians estimate as many as a quarter of them were eventually killed in Hitler’s extermination camps.

Why did the Roosevelt administration continue to erect barriers even as word of Hitler’s atrocities were becoming known? Historians name many factors, including anti-Semitism by the American public and the fear that the would-be immigrants posed a threat, variously, and incompatibly, described as either communism or fascism.

“The refugee has got to be checked because, unfortunately, among the refugees there are some spies,” FDR said at a press conference.

The episode has gone down in history as one of the great blots (along with the internment of Japanese-Americans) on the memory of one of the most revered American presidents.

Over time researchers would conclude that there were at most a handful of actual spies among the many fleeing Hitler. Trump himself has said there is “no proof” of his assertion that the “caravan” of refugees from Honduras, hoping to cross Mexico to the U.S. border, is filled with Middle Eastern terrorists. Separate studies would cast doubt on other fears about today’s immigrants. One from the Cato Institute last June, for instance, found that undocumented immigrants were half as likely to be incarcerated as native-born Americans.

In 1951, after the Holocaust and the other humanitarian catastrophes of World War II, a United Nations convention created the concept of refugee status, which offers protections to people fleeing persecution. The United States signed that treaty in 1967. The number of refugees granted asylum because they “fear persecution at home on the basis of their race, political opinion, nationality, religion or because they belong to a particular social group” has roughly fluctuated between 50,000 and 80,000 a year, but fell to 30,000 during the first year of the Trump administration.

“What they are trying to dismantle was created in the first place as a reaction to the Holocaust,” said Phil Orchard, associate professor of international relations at the University of Wollongong, who specializes in forced migration and civilian protection. “There is a huge irony here.”

The disconnect between Trump’s honoring Holocaust survivors and liberators, and his contempt for refugees from Central America, does not surprise Vered Vinitzky-Seroussi, a professor of sociology at Hebrew University of Jerusalem who is currently teaching a class in “Collective Memory” at the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York.

By collective memory she means national views of past events by people who were not actually there at the time, “the myths and ethos that (people of a country) believe they share.”

Political leaders tend to shape those narratives to serve them, she said in an interview, and although “the whole point of using past memories is to make sure we remember what happened so we won’t go through that same horrible thing again,” she warned, “if leaders only remember what they want to remember, we are not learning from the past but denying it.”

The phrase that has been adopted to keep alive the memory of the Holocaust is “never again.” The question for Americans today is, should it apply only to Jews?

_____

Read more from Yahoo News: