Trump Defenses of Georgia Phone Call Are Strong Arguments Against Trump 2024 Campaign

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

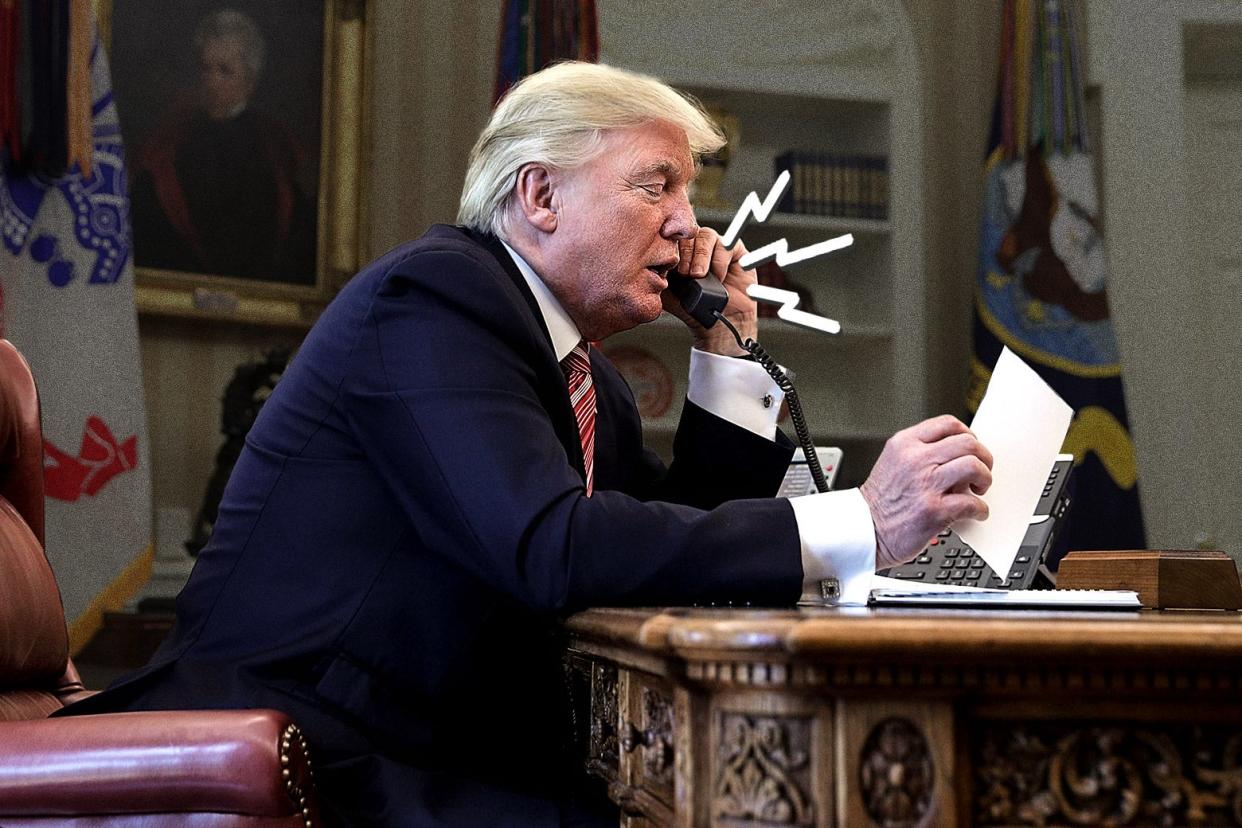

A recording of the Jan. 2, 2021, phone call during which Donald Trump asked Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger to help him “find 11,780 votes” became public almost immediately—and was just as quickly compared to the “smoking gun” tapes that helped bring down the Nixon presidency. Fair enough! With all due respect to storing classified documents in a resort bathroom, telling a local official to invalidate the precise number of votes that would be required to change the outcome of the election is the thing Trump has done with the most pronounced “I don’t think you can do that” feel.

The call is back in the news this week thanks to former White House chief of staff Mark Meadows, who testified Monday in a Georgia hearing related to the Fulton County district attorney’s allegations that he was part of Trump’s criminal conspiracy to overturn the 2020 election. Meadows is seeking to have his case moved from state court to federal court on the grounds that he is being prosecuted for activities that he undertook in his official capacity. He’s hoping that claim could secure him a more favorable jury pool (it’d be drawn from the more conservative northern district of Georgia as a whole, rather than just Democratic-leaning Fulton County) or, if the judge in his case is sufficiently convinced that Meadows was legally fulfilling executive-branch duties, an outright dismissal of charges.

According to Vox, the judge who listened to Meadows’ argument on Monday “appeared skeptical.” There are many problems with the case, but part of the gist is that White House employees are prohibited by law from attempting to influence the outcome of elections, and Meadows can be shown to have known that. As such, one of the things the former chief of staff argued in court on Monday was that he didn’t realize his late 2020 activities were related to partisan campaign efforts to overturn the election—i.e., that he didn’t understand the connection between President Donald Trump’s interest in vote-counting procedures in Georgia (and Michigan) and candidate Donald Trump’s ongoing efforts to reverse the results of voting in those states. From the Washington Post:

On several occasions, Mark Meadows claimed to have no knowledge of the Trump campaign’s efforts to contest the election results. On Donald Trump’s phone call with Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger, on Jan. 2, 2021, which Meadows participated in, he said he did not know that three lawyers on the call—Cleta Mitchell, Kurt Hilbert and Alex Kaufman—had participated in a campaign lawsuit against Raffensperger.

(Meadows said he didn’t remember how Mitchell, a prominent voter-fraud conspiracy theorist with whom he’d previously been in contact, had ended up on the Georgia call.)

In addition, when questioned about an Oval Office meeting he attended with Trump and Michigan state lawmakers, Meadows said he didn’t know that the campaign was contesting the results in that state.

According to Meadows’ testimony, he believed at the time that he was advancing the executive branch’s interest in “accurate and fair elections” and helping resolve Trump’s concerns about voter fraud in order to eliminate a “roadblock” to the “transfer of power”—in other words, that he did not understand, in January 2021, that Donald Trump was involved in election litigation for selfish reasons. (A recent New York Times piece that documents Meadows’ history of vacantly telling whomever he was talking to exactly what they wanted to hear suggests, troublingly, that this might actually be true.)

Meadows’ claims are similar to the one that Trump has made about his own behavior in 2020—that he believed the election was “rigged” against him as a matter of objective fact, meaning that his actions were reasonable attempts to secure the correct outcome. In his telling, the smoking gun was in fact a “perfect phone call.”

This line of reasoning was reintroduced to circulation by right-wing law professor Jonathan Turley on Fox News after the Fulton County indictments were announced:

You know, it makes perfect sense when you’re challenging an election to say, “You know, I only need around 11,000 votes.” So if you do a statewide review, that’s not a lot in a state like Georgia. That’s not criminal. That’s making a case for a recount.

Georgia, however, had already completed two recounts—one by hand and one by machine—by the time that Trump and Meadows spoke with Raffensperger. The fraud allegations the president was pursuing, moreover, were largely if not entirely sourced from random social media accounts and online message boards, and had already been dismissed by his own administration’s Department of Justice.

As a legal matter, Trump’s contention he truly believed that voting results were “rigged” has problems. Among them are the concept of willful blindness and Trump’s alleged statement that Vice President Mike Pence was being “too honest” in his response to the election, which would seem to imply an awareness that his own conduct was not honest.

Recall, too, that this trial may be taking place during the presidential campaign. Trump will be “defending” himself against a smoking gun by arguing, while his closest advisers testify that they could not possibly handle a gun without shooting themselves in the leg, that he believes guns are made out of cheese. And should he convince 12 jurors in Georgia and the District of Columbia that he is an insane person with low-IQ support staff, and secure a not-guilty verdict on the basis of such a triumph, he will then be asking the rest of his fellow citizens to reinstall him as president. It seems like a tall task, but if you think that it’s impossible, you’re probably the kind of person who is still 100 percent sure that the moon is made of rocks.