Trump-Care Would Leave Millions Uninsured While Somehow Costing More

Hillary Clinton’s plan for health care can best be summed up as Obamacare Plus: If elected, she would push to preserve the Affordable Care Act as-is, but she would add financial protections for struggling consumers.

Donald Trump’s health-care ideas, meanwhile, mirror his image as a renegade who will smash the system and rebuild it from scratch. He would annihilate the Affordable Care Act and replace it with an assortment of half-measures, most of which would benefit only people who are healthy and well-off, if anyone.

If enacted, Clinton’s health-care proposals would likely insure several million more people by making insurance cheaper for people in most income categories, according to a new analysis by the Rand Corporation and the Commonwealth Fund. Trump’s plan, meanwhile, would strip insurance coverage from 16 million people while raising out-of-pocket expenses for most people who aren’t insured through their employers, the report authors found. Both plans would increase the deficit.

“Mr. Trump does not understand health care.”

Though both candidates have mentioned a wide variety of health-care issues in their speeches and appearances, Rand economists focused on four of each candidate’s proposals for the analysis. The comparison is somewhat hindered by the lack of detail in many of Trump’s policy proposals. In some areas where Clinton put forth a comprehensive plan, such as long-term care and substance abuse, Trump provides vague ideas or none at all.

Clinton’s proposals are aimed at addressing many of the most common gripes about Obamacare: That insurance is still too expensive or that insurers are abandoning the Obamacare marketplaces and leaving people in some areas with few options.

Recommended: What It's Like to Have Irritable Bowel Syndrome

First, Clinton would add a tax credit of up to $2,500 for individuals whose out-of-pocket medical spending exceeds 5 percent of their income. She would also lower the maximum amount that people would have to pay toward insurance plans bought on the Obamacare marketplaces, from 9.7 percent of income to 8.5 percent of income for individuals who earn about $47,000 or less. She would also address the so-called “family glitch,” essentially fixing a problem where some families were wrongly deemed ineligible for Obamacare tax credits. Finally, she would add a public insurance plan to the Obamacare marketplaces—reviving an idea that was written into an early version of the Affordable Care Act, then taken out before the law was passed, and more recently suggested again as a possible solution for states where not enough insurers are participating in the Obamacare marketplaces.

“Clinton’s proposals are squarely aimed at consumer pocket issues, building on the ACA and in many ways trying to move beyond it,” said Larry Levitt, a senior vice president at the Kaiser Family Foundation. “The RAND numbers, while they don’t analyze all of Clinton’s proposals, show that Clinton’s policies would help move the country closer to universal coverage.”

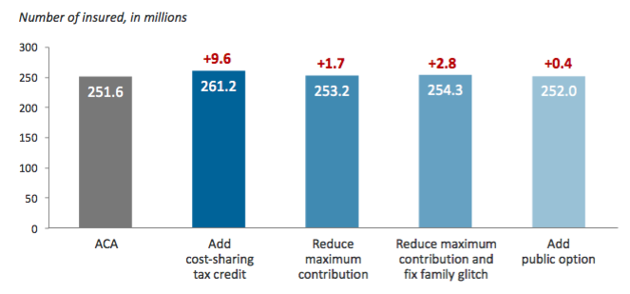

The report found that each of Clinton’s proposals would increase the number of insured people, with the tax credit having the largest effect. (That idea would also have the largest impact on the deficit, adding about $90.4 billion.)

Recommended: Finance Is Ruining America

Impact of Clinton’s Proposed Reforms on the Number of People with Insurance Coverage, U.S. Population Under Age 65, 2018

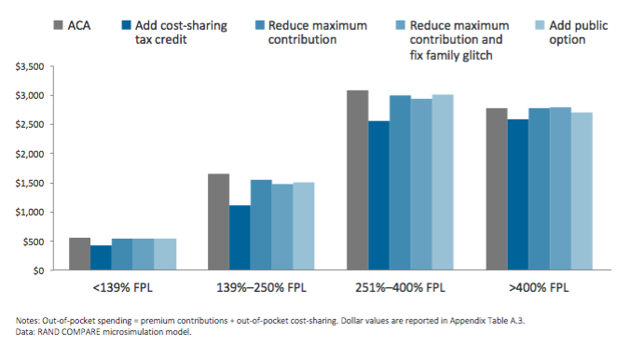

All of her proposals would also reduce the cost of health care for consumers, the report authors predict. With Clinton’s tax credit, individuals making between about $16,000 and $30,000 would see the biggest savings on insurance, about 33 percent less than what they spend now:

Impact of Clinton’s Proposed Reforms on Total Out-of-Pocket Health Care Spending of Insured People, by Income, 2018

The public option could insure an additional 400,000 people who have been left out of Obamacare, according to estimates from the report. But health-policy experts question its practicality.

Recommended: Is Ted Cruz About to Endorse Donald Trump?

Levitt, with the Kaiser Family Foundation, said it’s still not clear whether doctors would be willing to participate in a public-option plan or how it would entice more healthy people to buy insurance. “A public option plan would essentially be in the same boat as private insurers, with not enough healthy people to balance out the sick people who have signed up,” he said via email.

John E. McDonough, a professor at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health who worked on the Affordable Care Act, put it more bluntly: “I have a hard time thinking of a governor in his or her right mind who would want to set up one of these things.” Many red states are already hostile to Obamacare, and many have refused to expand Medicaid under the law. It’s not likely they’d be willing to swallow yet another reform that’s reminiscent of socialized medicine.

* * *

For Trump, Rand analyzed his plan to fully repeal the Affordable Care Act, including its more-popular reforms, such as prohibiting insurers from denying coverage to people with pre-existing conditions. Trump has also said he would allow individuals to deduct health-insurance premiums from their tax returns. He would fund Medicaid through block grants, in which the federal government would give states a fixed amount to spend on Medicaid enrollees, replacing the existing, more flexible spending scheme. Finally, he would promote the sale of health insurance across state lines.

There are a few other health-care policies listed on Trump’s site, but it’s not clear how they would affect enrollment levels. (For example, he wants to “Allow individuals to use Health Savings Accounts,” but HSAs already exist.)

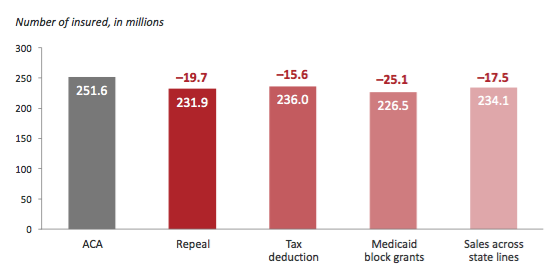

If the ACA was repealed, about 20 million people would lose their insurance coverage, and Trump’s other policies would not help the majority of them get insured again:

Impact of Trump’s Proposed Reforms on the Number of People with Insurance Coverage, 2018

Trump’s plans would lead to even greater numbers of poor people left uninsured. However, individuals who earn at least $30,000 and aren’t covered by an employer are slightly more likely to buy insurance coverage under his tax-deduction proposal than under Obamacare. “We estimate that 2.7 million more people with incomes over 250 percent of poverty would be insured with the tax deduction,” the report authors write:

Impact of Trump’s Proposed Reforms on Income Distribution of the Uninsured, 2018

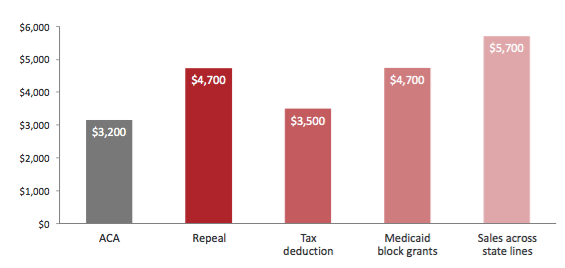

All of his proposals would also make health care more expensive for people buying insurance on the individual market, with the exception of high-income people, who would benefit from Trump’s proposed tax deductions:

Impact of Trump’s Proposed Reforms on Average Annual Out-of-Pocket Expenses for Individual Market Enrollees, 2018

“Without subsidies, middle income and lower income folks can’t afford to buy coverage,” McDonough said. “It’s only going to benefit higher-income people who are already buying coverage. [Trump’s plan] won’t expand coverage at all, and it will hurt the federal debt.”

Trump’s Medicaid block-grant idea has been put forward by other Republican policymakers, including the House Speaker Paul Ryan. Medicaid block grants won’t necessarily boot people from Medicaid rolls—the federal government could, after all, make the grants very generous—but past block-grant proposals have been stingier than the existing Medicaid system.

Selling insurance across state lines has been proposed by every Republican presidential nominee since 2005, as The New York Times’ Margot Sanger-Katz reported. The idea, built on the promise of competition in the free market, seems appropriate for a businessman like Trump. But it’s already been tried in some states, and it failed to catch on with insurers, who struggled to build up networks of doctors in other states.

Sara R. Collins, vice president of health-care coverage at the Commonwealth Fund, pointed out that if interstate insurance sales did pick up, insurers might flock to states with the weakest consumer protections.

“Across-state sales does have the potential to be a race to the bottom,” said G. William Hoagland, a senior vice president with the Bipartisan Policy Center who was previously a vice president of public policy for Cigna and a staffer for Republican senators. “I’m sure you could find companies that would sell much cheaper insurance policies, but the question is, what are you getting for that price?”

* * *

Rand’s projections should be interpreted with caution. Hoagland said that “at least they can give us the direction,” but that when it comes to health care, “I would not put a great deal of faith in the preciseness of the estimates that are produced.”

It’s worth remembering that the candidates’ health-care proposals are just that. All of these measures would have to go through Congress, which makes it unlikely that any of them will happen for a while.

“It doesn’t seem like the country is ready for another big health care debate,” Levitt said, “either to repeal the ACA or build on it.”

Though some of Trump’s ideas sound like conservative boilerplate, he doesn’t always hew to Republican orthodoxy. He surprised Democrats and Republicans alike, for example, when he suggested that Medicare should be able to negotiate drug prices, something that was also promoted by ultra-liberal Sen. Bernie Sanders.

But Trump also doesn’t stick to his own message when pontificating on health care. The drug-price negotiation idea, for instance, doesn’t appear on his campaign’s current health-care policy page. And though he advocates repealing Obamacare, he has also said he plans to cover the poor through Medicaid—and Medicaid expansion was one of Obamacare’s key pillars.

Clinton, of course, has her own critics. Merrill Matthews, a resident scholar at the Institute for Policy Innovation, said her measures would do nothing to address what he sees as the core problems with the Affordable Care Act, like rising premiums and deserting insurers. “All Clinton does is try to mask the problem by hiding the costs through subsidies,” he said.

But even critics of Obamacare have denounced Trump’s proposals as “a jumbled hodgepodge of old Republican ideas” that resemble “the efforts of a foreign student trying to learn health policy as a second language.”

Journalists from Politico and elsewhere were have been unable to identify where, exactly, Trump gets his advice on health care. Trump’s seeming allergy to choosing specific policies and sticking with them makes it hard to know what he would do in office.

Hoagland—who again, worked for Republicans for decades—put it most plainly, and terrifyingly:

“Mr. Trump does not understand health care.”

Read more from The Atlantic:

This article was originally published on The Atlantic.