Trump calls for changing, or killing, Iran nuclear deal. What’s next?

WASHINGTON — President Trump threatened Friday to walk away from the Iran nuclear deal unless Congress and the United States’ partners in the deal agree to a package of changes to ramp up pressure on the Islamic republic. Trump’s dramatic ultimatum did not by itself kill the accord but kicked its uncertain fate to Capitol Hill and six world capitals, including Tehran.

“In the event we are not able to reach a solution, working with Congress and our allies, then the agreement will be terminated,” Trump said in a speech from the White House’s Diplomatic Reception Room.

The 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), backed by then-President Barack Obama, imposed a series of internationally enforced safeguards on Iran’s nuclear activities — inspections, monitoring, dismantling of some facilities — meant to prevent Tehran from developing the world’s most devastating weapons. In return, the United States, Britain, China, France, Germany and Russia eased economic sanctions that had been imposed on Iran over its alleged pursuit of nuclear arms.

Trump acted under a 2015 law requiring him to declare every 90 days whether Iran is complying with the agreement and to certify — or not — that the suspension of the nuclear-related sanctions is in America’s national interest as well as “appropriate and proportionate” to Tehran’s compliance. The next deadline would have been on Sunday.

On Friday, the president said Iran had violated the “spirit” of the agreement but listed several breaches that Iran, as is allowed under the JCPOA, remedied. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson told reporters late Thursday that “we don’t dispute” that Iran is technically complying with the accord. And Defense Secretary James Mattis recently testified to Congress that the agreement is in the national security interest of the United States.

Trump did not call on Congress to reimpose nuclear-related sanctions, which would almost certainly kill the agreement and potentially put the United States on a path to war with Iran.

But the president, who vowed during his 2016 presidential campaign to tear up the deal in its current form, listed a series of complaints about the accord: It does not cover Iran’s intercontinental ballistic missile programs or what Washington denounces as Tehran’s support for terrorists, and some of its key restrictions “sunset” (a legislative term for “expire”) in five, eight, 15, 20 or 25 years.

“Congress has already begun the work to address these problems,” Trump said, describing nascent legislation that would toughen enforcement of the JCPOA, stymie Iran’s development of intercontinental ballistic missiles “and make all restrictions on Iran’s nuclear activity permanent under U.S. law.”

Trump’s speech drew a rebuke from the European Union’s foreign policy chief, Federica Mogherini, who declared that “we cannot afford as the international community to dismantle a nuclear agreement that is working,” and that Trump by himself did not have the authority to terminate the agreement. Russia called Trump’s remarks “extremely troubling.” Iran said it would “stick to” the deal for now and in fact has recently suggested that it could stay in even if Washington quits the agreement.

In a joint statement, Britain, France and Germany recommitted themselves to preserving the deal, calling it “the culmination of 13 years of diplomacy” and saying that saving it “is in our shared national security interest.”

But London, Paris and Berlin signaled an openness “to take further appropriate measures” to tackle Iran’s missile programs and regional activities “in close cooperation with the U.S. and all relevant partners,” while urging Iran “to engage in constructive dialogue.”

There are several potential paths from Trump’s demands, each with dramatically different ramifications for the future of the agreement and U.S. national security.

While Trump’s speech technically started a 60-day clock for Congress to decide whether to reimpose nuclear-related sanctions, no one seriously believes that lawmakers will restore those punitive measures. Even diehard Iran hawks on Capitol Hill have said that now is not the time to do so, and Trump did not make that request in his speech.

Instead, lawmakers have until the next certification — roughly 90 days from now — to modify the 2015 law. One very real possibility is that they will fail to rally the 60 votes needed to overcome a potential Democratic filibuster in the Senate.

“I don’t want to suggest to you this is a slam-dunk up there on the Hill. We know it’s not,” Tillerson said late Thursday.

Congressional inaction would leave matters up to Trump, who could withdraw from the accord or, more dramatically, refuse to waive economic sanctions that affect not only Iran but European firms and American companies hoping to do business with the Islamic republic.

Either way, Iran and U.S. partners in the agreement would need to decide whether to preserve the accord without the United States. Iran recently suggested it would stay in the JCPOA, but if it renounced the deal and cast off its limits on nuclear work, that could set the stage for a military confrontation.

Another possibility is that Congress would successfully modify the 2015 Iran Nuclear Agreement Review Act (INARA) to say that Washington will reimpose nuclear-related sanctions if Iran proceeds with intercontinental ballistic missile development or takes advantage of the “sunset” provisions to resume nuclear work that puts it closer to developing a bomb.

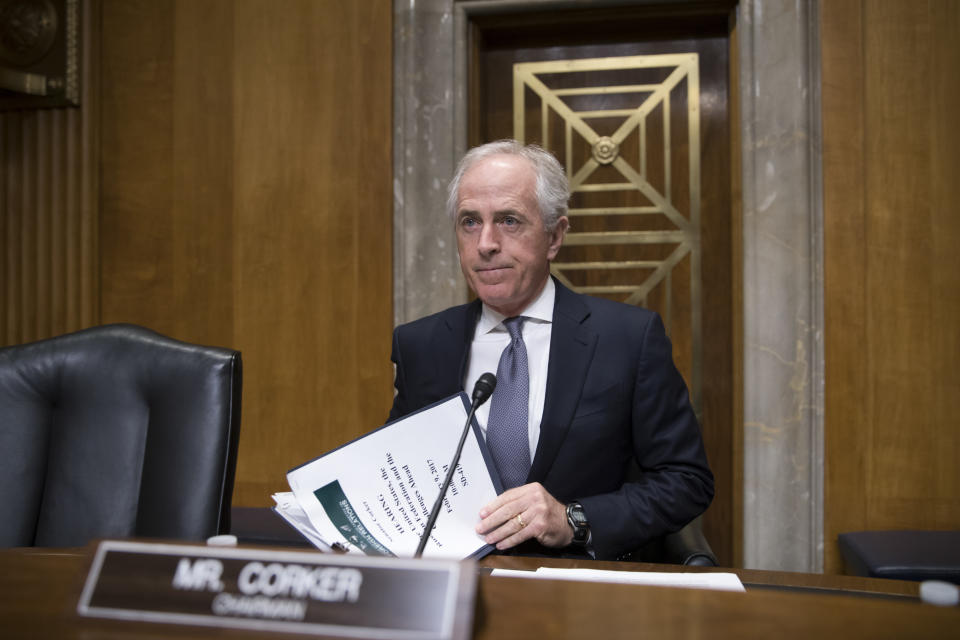

“We’re going to abide by the agreement, but we also are going to freeze in place the limitations that are there” with the threat of “unilaterally” reimposing sanctions, Senate Foreign Relations Committee Chairman Bob Corker, a Republican who is drafting such legislation, told reporters Friday.

Corker said the trigger would be if Iranian nuclear activities shorten Iran’s “breakout” time — the time it would take the regime to build a nuclear bomb if it decided to do so — from the current estimate of one year. And the senator denied that a unilateral U.S. declaration that the “sunsets” don’t apply to U.S. sanctions would violate the agreement.

“That’s not in violation of the JCPOA anyway from our standpoint. This has been run through the White House legal counsel and the State Department’s legal counsel,” he said on a conference call with reporters.

But a top U.S. official who worked on the deal for Obama said that Corker’s sunset provision would violate the agreement. “What’s wrong with it is that it constitutes a unilateral renegotiation of the deal by the United States Congress,” former deputy national security adviser Ben Rhodes told reporters.

If Congress successfully amended the INARA, the U.S. law, Tillerson said, that would put pressure on allies and Iran.

It’s “unlikely” that Iran would accept amending the JCPOA, the international agreement, Tillerson acknowledged. “It more likely means that we would undertake an initiative to have a new agreement that doesn’t replace the JCPOA but addresses these two issues and lays along beside the JCPOA.”

Lurking in the backdrop of all these laborious efforts is the possibility of U.S. military action against Iran.

Asked about that possibility shortly after his speech, Trump replied, “We will see what happens with Iran. We’re very unhappy with Iran. They have not treated us with the kind of respect that they should be.”

Read more from Yahoo News: