Why Donald Trump would be at a disadvantage in a brokered convention

Donald Trump at a rally at Macomb Community College in Warren, Mich., on Friday. (Photo: Carlos Osorio/AP)

A brokered national political convention has for decades been something of a political unicorn — much discussed, but never actually materializing. But with more than half the Republican Party opposed to frontrunner Donald Trump, yet also split between his three major remaining opponents, the conditions are as ripe as they have ever been for a showdown on the floor of a Republican National Convention this summer.

That possibility has Trump supporters already hurling accusations that Republicans plan to “steal” the GOP nomination from their candidate. In a brokered or contested convention, a nominee is chosen through multiple rounds of voting by delegates from all 50 states and six U.S. territories.

Marco Rubio’s campaign is looking ahead at that possibility and hopes that by openly discussing the arcane mechanics of how voting delegates are selected to the convention, it can defang the Trump-backers’ argument to some degree.

Trump supporters will be enraged if Trump wins the most states and delegates but falls short of the 1,237-delegate threshold needed to secure the nomination, and then loses during balloting at a contested convention.

But Rubio’s campaign is already stressing that if such an outcome occurs, it will be the result of a multistep process that is not a secret to anyone. But the state-by-state system of selecting delegates does showcase the fact that to the extent that any real GOP establishment exists in the modern era, it’s at the less-high-profile state and county levels. A brokered convention would come down to the votes of thousands of little-known local party officials with a deep commitment to the well-being of the Republican Party.

“If Donald Trump can get to 1,237 delegates, he’ll be the nominee and we’ll shut up,” said a Rubio ally helping to plan for the convention but not authorized by the campaign to talk openly about the process.

But if Trump cannot get that number and has to face a brokered convention, the reply to Trump’s supporters will be: “Them’s the rules.”

Of course, the more that Trump’s rivals can actually win states rather than come in second or third in them, the less they will need to rely on an argument about the rules in July at the convention in Cleveland.

But if Rubio, a U.S. senator from Florida, Texas Sen. Ted Cruz, or Ohio Gov. John Kasich all stay in and do well enough to amass a substantial number of delegates of their own and Trump cannot reach the 1,237-delegate threshold, then the convention will be deadlocked and will have to go to multiple ballots, or votes.

“It’s going to be the most exciting time,” said Kasich Thursday, noting that if he wins Ohio there likely will have to be a brokered convention.

Mitt Romney, the GOP’s 2012 nominee, advocated Thursday that the Republican candidates adopt an explicit strategy of splitting the vote between Rubio, Cruz and Kasich in order to block Trump from winning the nomination before the convention.

“Given the current delegate selection process, that means that I’d vote for Marco Rubio in Florida and for John Kasich in Ohio and for Ted Cruz or whichever one of the other two contenders has the best chance of beating Mr. Trump in a given state,” Romney said in a high profile speech at the University of Utah in which he flayed Trump as a “phony” and a “fraud.”

Former Republican presidential nominee Mitt Romney speaking out against the candidacy of Donald Trump on Thursday. (Photo: Jim Urquhart/Reuters)

Some news organizations reported an effort by Romney lieutenants to organize an anti-Trump effort at the convention. But an attempt to mastermind some kind of overarching convention plot underestimates the complexity of each state’s process of selecting delegates — and how much national organizational work it would take to influence it.

On the first ballot at a brokered convention, delegates from all states and territories except Colorado, Wyoming, North Dakota, Virgin Islands, American Samoa, Guam and a few from Louisiana must vote for the candidate who won their support on the day of their state’s primary or caucus.

But on the second ballot, “That’s when the action gets really interesting,” the Rubio supporter said. That’s when 55 percent of a state’s delegates will be free to vote for whomever they want.

By the third ballot, 85 percent of all the delegates will be free agents.

At that point, the 2,472 delegates on the floor of the convention would become major political players whose loyalties would decide the nomination. And the process by which those delegates were chosen will come under a microscope.

Each state is different. Take Iowa for example, the first state to vote in the primary cycle. On Feb. 1, Iowa held caucuses in which Republican voters wrote down the name of their choice for president on pieces of paper. But that night each precinct also chose delegates to a convention for their local county.

A week from Saturday, on March 12, each of Iowa’s 99 counties will hold conventions, where they will elect delegates to two more conventions. First, the counties will vote on delegates who will attend a congressional district convention. There are four districts in the Hawkeye State, and on April 9 each will hold a convention to elect three delegates to the national convention.

The county conventions also elect delegates to a statewide convention, to be held on May 21. At that convention, delegates will vote again, to elect 15 more delegates to the national convention.

Iowa sends 30 delegates to the national convention in all: 12 from the congressional district conventions, 15 from the state convention, and then the three last slots are filled by the state’s GOP party chairman and its two members of the Republican National Committee.

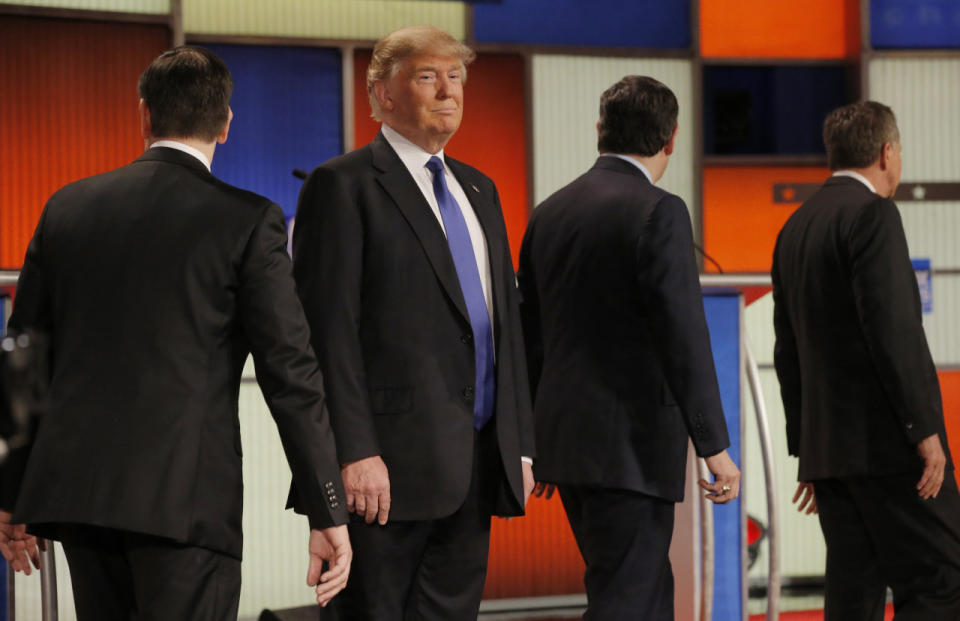

Donald Trump and rivals, from left, Marco Rubio, Ted Cruz and John Kasich head to their podiums at the start of the Republican candidates’ debate in Detroit on Thursday. (Photo: Jim Young/Reuters)

Now take the complexity and the unique local flavor of that process and multiply it by 56.

The result is that convention delegates are people who are deeply plugged into small relational networks in their communities and states. The time and effort they put into doing the work of running their local party year in and year out is rewarded by a trip to the national convention every four years.

“I don’t think Trump is that well situated to participate in this process,” said the Rubio ally. “These are people who have done this for many years, oftentimes under the direction of their Republican governor.”

“Of course, there may be others who are trying to wrestle away control of the state party,” he added.

Ben Ginsberg, a veteran Republican lawyer who is an expert on the nominating rules, said that Trump’s campaign is certain to organize its own slates of delegates in as many states as possible.

“I also think the Trump people understand the state-by-state need to organize the state conventions and the state executive committees,” Ginsberg said Thursday on MSNBC.

Up until the 1960s, delegates were largely controlled by party bosses from the major cities and from Washington, who gathered at the convention to decide the nominee. But in the decades since the nominating process was changed in the 1970s, handing power over to voters more directly through the primaries and caucuses, delegates have been little more than props, stage actors in a nationally televised four-day infomercial for their party’s nominee.

But now that system, relatively stable for decades, could be shaken up and transformed again — perhaps more by the little-known men and women who have worked their way up the party machinery in every state than by any group of Washington insiders.

And the hope of Trump’s opponents is that they will be open to an alternative in July. “Generally speaking, the people who participate in this process are pretty friendly to our candidate,” said the Rubio supporter.