The true story of how American landowners overthrew the Hawaiian monarchy and forced US annexation

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Though many Americans think of a vacation in a tropical paradise when imagining Hawaii, how the 50th state came to be a part of the U.S. is actually a much darker story, generations in the making.

From its indigenous Polynesian population to its role in World War II and contemporary global influences, the archipelago and its history are a legacy worth celebrating.

Still, to honor and truly appreciate the significance of the state’s role in a country that prides itself as being “The Land of Liberty,” it’s important to go back and understand its origins. Before it became branded as the country’s destination for leisure and relaxation, Hawaii was a monarchy. Illegally overthrown in 1893, the former sovereign state was overrun by American and European businessmen whose racial attitudes and political interests heavily influenced the course of history and the experiences of the land’s indigenous people.

Read on for a timeline of how the illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian monarchy unfolded in a gradual and parasitic way.

Late 18th Century to early 19th Century — the arrival of James Cook

Roughly 1000 to 1500 years after Polynesians used stars to make their way across the ocean and settle on the Hawaiian Islands, British cartographer Captain James Cook landed on the island of Kaua'i in 1778.

He became the first European to touch the ground there, and his journey chartered a path for subsequent Western explorers, missionaries and more to come to the island with new ideas, technologies and concepts that quickly began to reshape Hawaiian society.

1810 — More settlers, more problems

King Kamehameha I began as the ruler of the island of Hawaii, often referred to as the Big Island. He eventually unified the islands of Hawai'i, Maui, Moloka'i, O'ahu, and Kauai for various purposes, including political stability and defense against the increasing arrival of Europeans.

After Cook’s landing, the increasing interaction with the wider world brought outside diseases to the island nation, Noah Hanohano Dolim, an assistant professor of history at the University of Hawaii Manoa, tells TODAY.com.

"From the time of Captain Cook to the late 1800s, Hawaii was looking at about, 90 to 95% population loss," he says of the native population. "(They) had a number of different epidemics... syphilis outbreaks, cholera, measles, whooping cough."

He notes that many of the Native Hawaiian royals also died in the various epidemics. "So you also have not only commoners dying but also a lot of other chiefs had died," he explains, "which really narrowed the monarchy down a lot."

1826 to 1848 — Land struggles

By 1826, the tension between the Hawaiian people and Westerners had gravely escalated, and Kamehameha III — the son of King Kamehameha I — had come into power.

Kamehameha II — the eldest son of Kamehameha I — ruled only for five short years before dying from measles in 1824.

His brother, Kamehameha III, changed the island’s ruling system to a constitutional monarchy during his reign, according to The Archival Collections at the University of Hawaii School of Law Library. With this, he granted land ownership rights to Native Hawaiians and foreigners.

"He saw the opportunity to protect his people, but then, in the long run, it backfired because it eventually allowed for foreigners or non-Hawaiians to purchase lands in Hawaii," Dolim tells TODAY.com.

Mid-19th Century — The arrival of indentured servants

According to “Sugar & the Rise of the Plantation System” by James Hancock, sugar was a key component of the colonization of the New World by Europeans. In the mid-19th century, as the United States became swept up in the storm of the Civil War (which lasted from 1861 to 1865), sugar supplies from Louisiana ceased, and sugar cultivators set their sights on Hawaii.

By 1852, exporters began to bring Chinese indentured servants to work on sugar plantations. Soon, other ethnic groups started to arrive, including Portuguese, Japanese, Koreans, Filipinos, Spaniards, Russians, and Norwegians. The result was the multiculturalism of Hawaii and a wedge for Americans and Europeans to use in order to exert economic and political influence over Hawaii.

Late 19th Century: Sugar success sets up a bitter fate

By the late 19th century, sugar exports had thrust Hawaii into the global economy, and American businessmen were taking full advantage of the land’s economic promise.

Kamehameha III’s granting of land ownership rights contributed to Americans’ increasing ability to snap up land holdings and gain political influence. According to “Preparing to Be Colonized: Land Tenure and Legal Strategy in Nineteenth-Century Hawaii,” in making direct purchases and garnering land leases from Native Hawaiians, foreigners began to gain exclusive rights to the land.

The success of the plantation owners meant Hawaii would become essentially an oligarchy, with a wealthy class ruling the rest of the island chain's population, Dolim says.

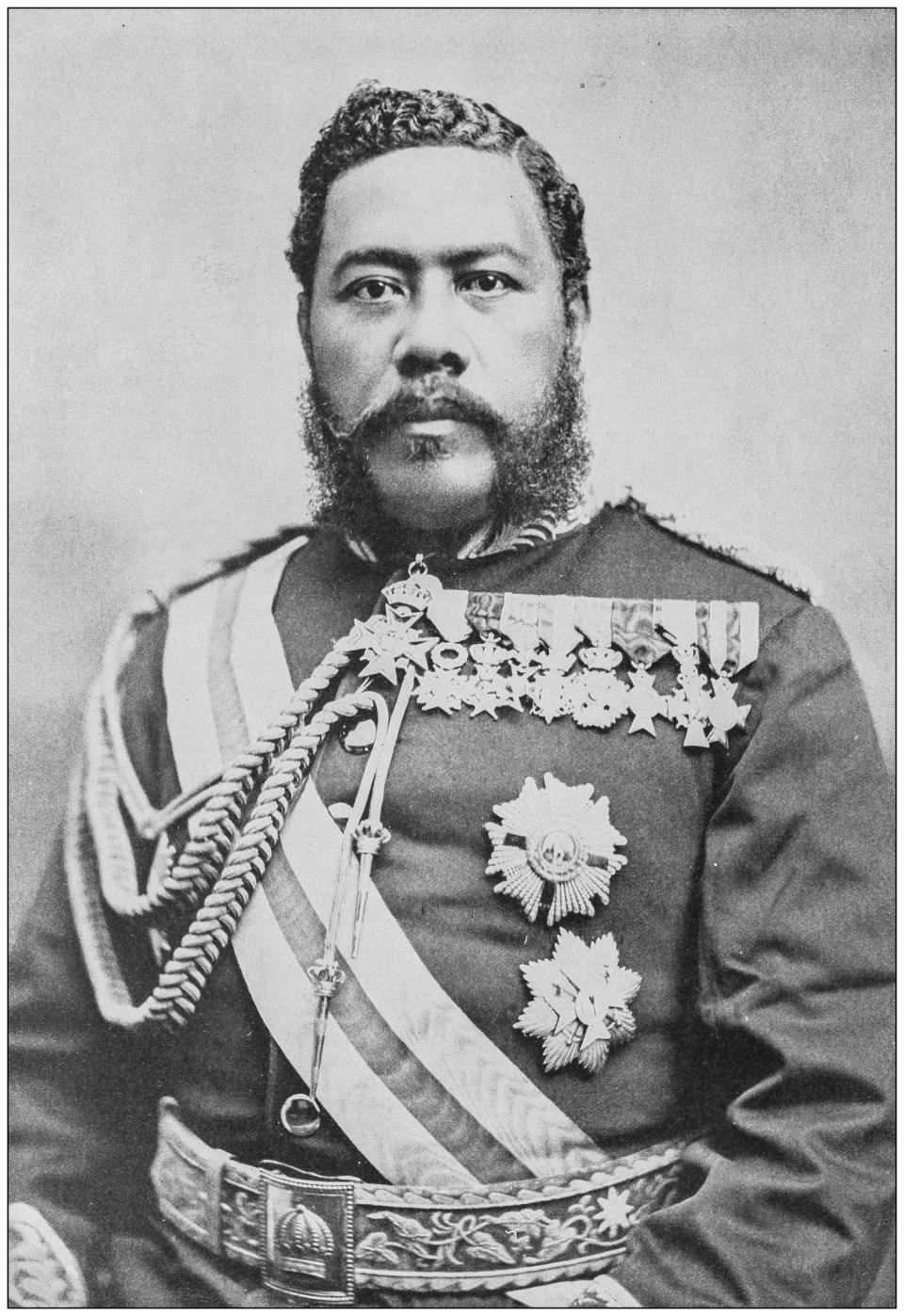

February 12, 1874: King Kalākaua takes the throne

Twenty years after Kamehameha III’s reign ended in 1854, King Kalākaua was elected to the throne in 1874. He would become the last king of Hawaii, ruling from 1874 to 1891.

He was known as the “Merrie Monarch” for his love of the arts and cheerful disposition. Kalakaua is also known for celebrating the traditional Native Hawaiian dance, the hula.

1875 — The Reciprocity Treaty between the Kingdom of Hawaii and the US

While king, Kalākaua negotiated the Reciprocity Treaty of 1875, which allowed sugar and other products to be exported to the U.S. duty-free.

His kingdom saw tons of growth as a result.

According to "The Hawaiian Kingdom, Vol. 3," by Ralph S. Kuykendall, the year Kalakaua ascended the throne, the island nation exported $1.84 million in products. By 1890, the last full year of his reign, Hawaii exported $13.3 million in goods — an increase of more than 720%.

July 6, 1887: The Bayonet Constitution

In 1887, the king was forced to sign a new constitution stripping him of his power and many native Hawaiians of their rights.

A militia affiliated with the Hawaiian League — a non-native political party mostly made up of U.S. businessmen — threatened the king and forced him to sign the constitution. It became known as the Bayonet Constitution because Kalākaua signed it under duress.

In her memoir, Kalākaua's sister Lili'uokalani, who would later become queen, wrote that the king signed the new constitution because he was afraid of being assassinated if he refused.

"It may be asked, 'Why did the king give them his signature?'" she wrote of the incident in her 1898 book, "Hawaii’s Story by Hawaii’s Queen." "I answer without hesitation, because he had discovered traitors among his most trusted friends, and knew not in whom he could trust; and because he had every assurance, short of actual demonstration, that the conspirators were ripe for revolution, and had taken measures to have him assassinated if he refused."

Dolim, in speaking to TODAY.com, confirms that it was likely the king felt pressured to sign the constitution, even though "we don't know exactly" what Kalākaua was threatened with.

"He definitely knew they had the means to enact violence," Dolim says. He adds that the military of Hawaii at the time wouldn't have been much protection from a threatened American invasion.

"I don’t know how (Hawaii) would have fared if they actually resorted to violence," he says. Dolim adds that Kalākaua's 1887 signature on the new constitution was arguably, the legal end of the king's reign.

"Because Kalākaua didn’t really have sovereignty over the kingdom anymore," Dolim says. "I think at that point, the writing was kind of on the wall."

1891 — The last Hawaiian monarch

Kalākaua, already ill, went to California in late 1890. In his absence, his sister Lili'uokalani was named regent. While abroad, Kalākaua fell into a coma and died on Jan. 20, 1891.

Upon his death, his sister, now Queen Liliʻuokalani, ascended to the throne.

1893 — Overthrow of the monarchy

Two years after she became the monarch, Queen Lili'uokalani faced a coup planned by businessmen from the United States and Europe as well as some native Hawaiian allies. Among the men were prominent figures like Sanford B. Dole, who founded the Hawaiian Pineapple Company, which later became Dole plc, best known today for its banana and pineapple products. The organizers of the coup justified their actions by forming the Committee of Safety, citing Queen Liliʻuokalani’s attempts to strengthen the monarchy’s power as a threat.

The coup went forward with the support of John L. Stevens, the United States Minister to Hawaii, and US Marines from the USS Boston.

By January 17, 1893, the overthrow of the monarchy was complete.

1894 — Hawaii becomes a republic

The Republic of Hawaii is established, with Sanford Dole as its president. During this time, Queen Liliʻuokalani was arrested and imprisoned at her home, Iolani Palace.

1898 — The annexation and end of a kingdom

Despite opposition from many native Hawaiians, Hawaii was annexed by the United States in 1898.

Though Dole had sent a delegation to Washington D.C. four years earlier seeking annexation, a special investigation ordered by President Grover Cleveland had found that Queen Liliʻuokalani had been overthrown illegally and ordered the American flag be lowered from Hawaiian government buildings.

Dole never turned over power, however, and argued the U.S. couldn't interfere in the internal affairs of the island nation.

Liliʻuokalani and a delegation of fellow native Hawaiians organized a mass petition to avoid annexation but failed. In a congressional move known as the "Newlands Resolution," the Hawaiian Islands were officially annexed by the United States and Sanford Dole became the first governor of the territory.

Speaking to TODAY.com, Dolim notes that the joint resolution passed was "actually just a domestic bill" and not a traditional treaty of any kind between two nations.

"Because they knew that if it was put to a vote in Hawaii, that that vote wouldn’t have passed," he says.

The annexation of Hawaii as a U.S. territory was finalized by August 12, 1898, and marked the end of the island nation's independence. Hawaii would not become an official U.S. state until 1959.

This article was originally published on TODAY.com