True Grit: Abilene aviatrix flew with grace

Who was Vera Dawn Walker? Bird Thomas knows.

“She was a pistol,” she said.

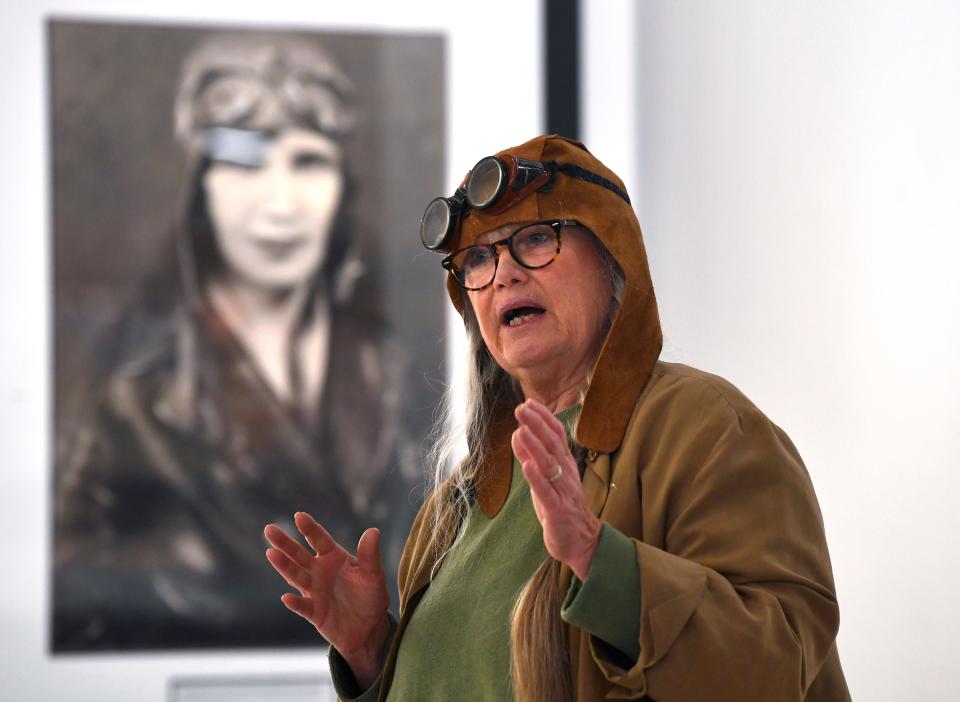

Burgess “Bird” Thomas has been the tip of the spear in recognizing Walker, whose career as a nationally known aviatrix from 1929 to 1931 is now on display in the terminal at Abilene Regional Airport.

Walker died June 18, 1978. She was 81, and by that time her career in aviation was a distant, if not treasured, memory. Walker might be the most famous pilot you’ve never heard of.

“She had so many fun nicknames,” Thomas said. “They called her the Daring Damsel, the Flying Flapper, the Tiny Texan and even Lady Bird, which I kind of liked.”

At 4 feet, 11 inches and 95 pounds soaking wet, Walker was often labeled by the press of the day as the World’s Smallest Pilot. Raised in the Abilene area, even if you’d never met her, you’ve met her type.

“You know, she was described by her peers as petite, big blue eyes, easy to smile,” said Traci Sterling, whose mother’s first marriage had been to Walker’s nephew, Kerry. “In another article, Vera Dawn was gritty and in-your-face, fearless.”

The mystery begins

The unraveling of Walker’s story began with the discovery of her grave in south Taylor County and the discovery of a battered suitcase in Kerry’s home after his death. The suitcase contained answers to many of the questions surrounding Walker’s life.

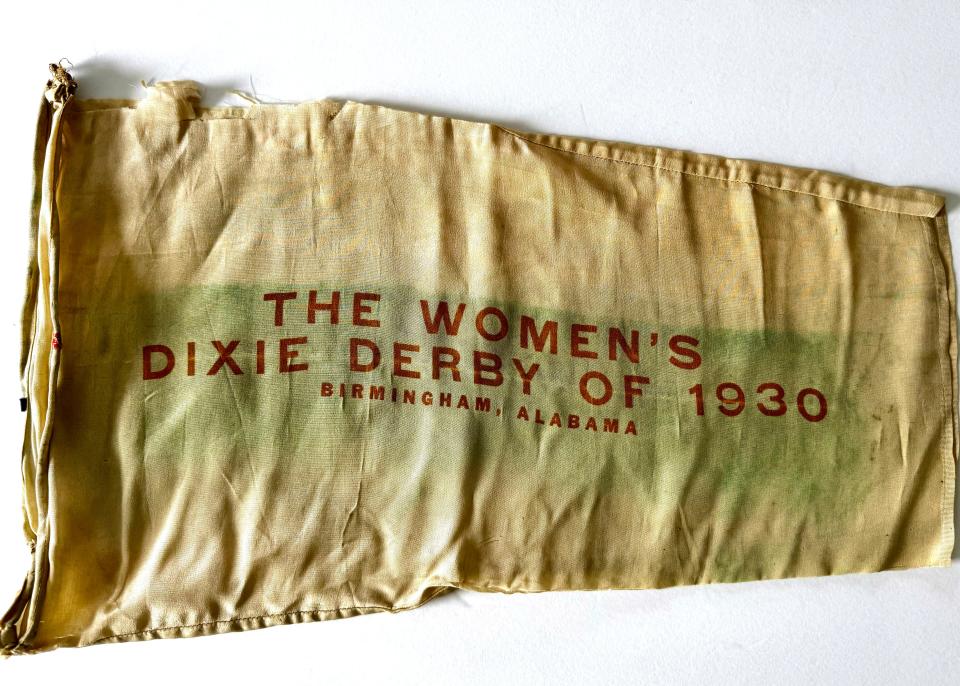

She was a charter member of the Ninety-Nines, a group of 99 women pilots formed in the successful wake of the 1929 Women’s Air Derby, a race that included her friend Amelia Earhart.

Everyone has heard of Earhart but why not Walker? In a word, publicity.

“Amelia Earhart deserves everything she got,” Thomas said. “But it’s all hype.”

George Putnam was Earhart’s publicist. His family publishing business had led him to author a successful account of Charles Lindbergh’s flight across the Atlantic.

According to the Purdue University Archives, Putnam sought out Earhart after being urged by a wealthy London socialite to find a woman pilot and give her story the same treatment.

Putnam found the hitherto unknown Earhart and employed the same formula as he did for Lindbergh. A few years later, the two were married.

But when it comes to Walker’s story, the details aren’t as clear as Earhart’s. Even her grave in Cope Cemetery near Lawn was unmarked until a tombstone was placed there six years ago by the Ninety-Nines. Loretta Fulton highlighted the placement of the marker in the June 16, 2018, Abilene Reporter-News.

After Kerry Walker died in 2019, Sterling’s mother Amelia Jane Sharp assisted her grandsons with sorting his belongings, discovering a suitcase containing souvenirs and memorabilia belonging to the aviatrix.

Sharp remembered meeting Walker when she was 19.

“She was very energetic, and she commanded everybody's attention when she was around,” Sharp recalled. “She told her stories, and everybody had to listen.

“She was just an interesting person.”

For her brothers

No one was sure what to do with the material. Sterling, Sharp’s daughter from her second marriage, had a background in marketing. The family agreed that she seemed the logical choice in bringing the story of Vera Dawn Walker to light.

Sterling had grown up with her now-deceased brothers, Tim and Tate Walker. More than anything, researching Vera Dawn Walker was her way of honoring her late siblings.

“I took it home with me to Virginia, with the full intention of just donating it to the Air and Space Museum in D.C.,” Sterling said by phone. “Which just made perfect sense to me, to be there with all her peers.”

The museum was interested, but nobody there could guarantee Walker’s material wouldn’t just go into storage. That wasn’t good enough.

“You know growing up in Texas, I know better than a lot of people that Texas pride runs deep, and it is real,” she said. “Texans need to know about her. So, I started with Abilene and here we are.”

'Airplanes don't know if you're a boy or a girl'

Nancy Robinson Masters was one of the over two dozen aviation history enthusiasts who gathered March 15 to dedicate Walker’s exhibit at Abilene Regional. A longtime pilot, she is also a member of the Ninety-Nines Abilene chapter.

“When I learned how to fly in 1967, there was still a law under the Federal Aviation Administration that for a woman to take flying lessons, she had to have written permission from her husband, father or male significant other,” she recalled.

Her late husband Bill was a flight instructor with a simple guiding principle.

“Airplanes don't know if you're a boy or a girl. It's, Can you follow the directions? Can you read the instructions? Can you handle the requirements? That's all that matters,” Masters said.

Grit with grace

There wasn’t a Federal Aviation Administration when the flying bug first bit Walker. The suitcase in Sterling’s home provided evidence of the future-flyer’s move from the Big Country to Los Angeles, and its booming silent movie industry.

“I have some images of her, like one where she's kind of dressed in a little cowgirl outfit, and some that are a little bit more demure with a soft focus,” Sterling said. “Clearly not flying photographs.”

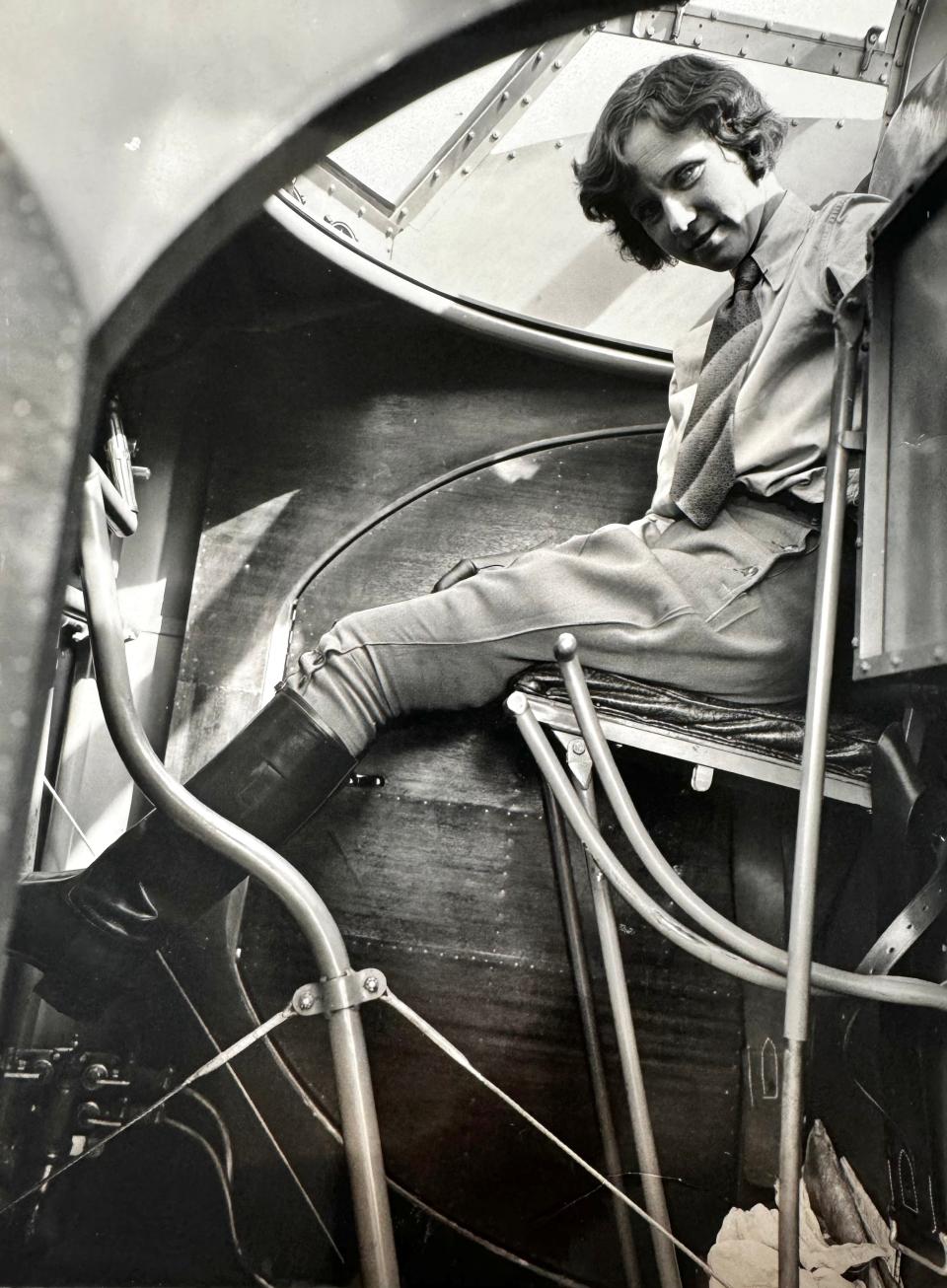

It was when Walker was an extra on Tom Mix’s 1925 silent feature, "Riders of the Purple Sage," where that flying bug came home to roost. In a 1972 interview in the Arizona Republic, Mix and Walker were the only two who took a pilot up on his offer for an aerial tour of the Hollywood hills.

“Before we touched the ground, I knew that I had to learn how to fly,” Walker said.

Still, it would be three years before she finally received her pilot’s license. She parlayed those skills into her career as a film industry stunt double and pilot.

“I've learned a lot of tidbits about Vera Dawn, but what I've come to realize is that she was fearless. She was a daredevil. She had grit,” Sterling said. “Grit with grace, she parachuted out of airplanes!”

But that didn’t mean she didn’t want to look good, too.

“In some of these pictures, quite frequently she is the only female pilot that's still in a dress,” Sterling added. “The rest of them are wearing their flying pants and their jackets and that sort of thing.”

A tragic turn

But adventure wasn’t her only incentive for learning to fly.

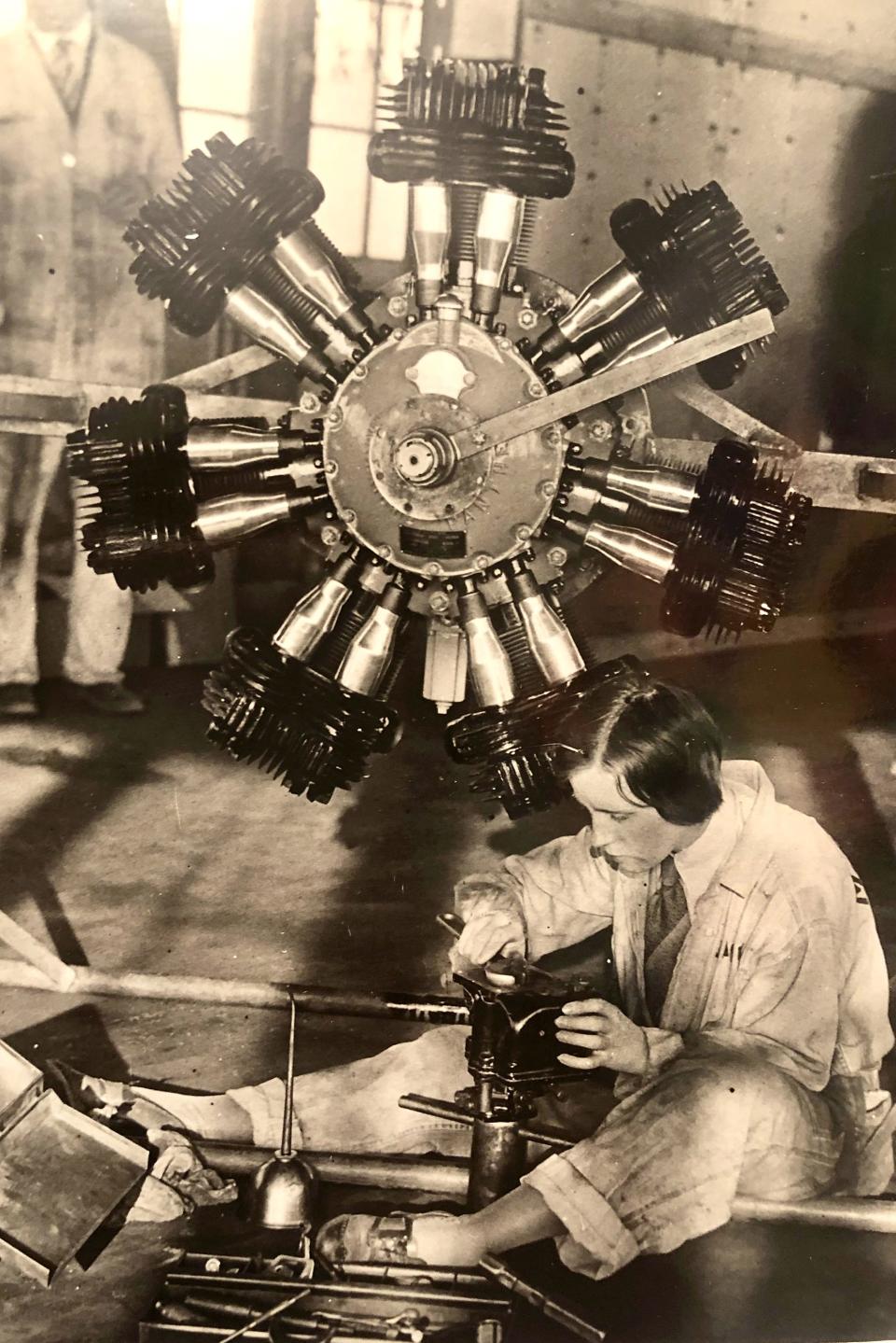

Raymond “Chub” Compton was one of her flight instructors at The Aero Corporation of Los Angeles. Walker’s skills as a pilot and her relationship with Chub took off at the same time.

“She really became engrossed with learning to fly when she met this guy,” Sterling said. “Which isn't that the common girl-meets-boy story?”

And yet, it was not to be.

Compton’s plane crashed on June 1, 1929, during a lesson with an 18 year-old student. At his funeral, Walker flew over the memorial, dropping flowers as she passed.

“She was quoted as saying she fell in love with flying because she fell in love with a pilot,” Sterling said. “He died three weeks before their wedding date.”

Still a sensation

After the race, Walker picked up what in later years might be considered endorsement deals.

“Vera Dawn was promoted as a demonstration pilot for the Panther Motor Company,” Sterling said. “She was also hired by Pickwick Airways, which, if I understand it correctly, was the first airline that would fly from Los Angeles to San Francisco.”

Pickwick didn’t last beyond 1930, however. After that company foundered, Walker created a sensation with Denver newspapers when she moved to the Mile High City.

That coverage only heightened when on Christmas Eve 1931, Walker was mugged on a city street. Sterling found the account of the robbery in both the Rocky Mountain News and the Denver Post.

“A young man stepped from behind a clump of shrubbery and grabbed for my purse. I held to it and he placed a hand over my mouth to keep me from screaming and I tried to fight him off as he struck me on the head. That's all I remember,” said Walker two days later.

In her bag was $25 and her pilot’s license. She was found by two brothers driving by who saw her feet sticking out from the curb.

The money wasn’t the most valuable thing in her bag, however. Walker was scheduled to fly the following week.

“The thug who slugged me can keep my purse and my money, I'll even forgive him for knocking me unconscious if he will just send back my license,” Walker added.

Unfortunately, the license never reappeared, and she was forced to wait on a new one from Washington before she could resume flying.

Walker’s flying career began to fade after that. After a flight to Guatemala, she was diagnosed with tuberculosis. Moving to Arizona, she bought a copper and turquoise mine, married again briefly and then just lived her life.

The legacy of Vera Dawn Walker

What would that be?

“For me, and for Abilene, it's that she persevered against the odds to prove that ordinary women from ordinary circumstances could achieve great things,” said Robinson Masters.

Sure, she added, Walker did stunt piloting but was likely assisted in that endeavor by her diminutive stature.

“She could hide down in the airplane, and they could stick a male head on the picture and make it look like a man (was flying),” she said, laughing. “I mean, it was hysterical.”

But that still doesn’t encompass the broad strokes of Walker’s example to not only women but to anyone from a small town with the courage to leave their rural home for the wider, more exciting — and more dangerous — wide open world.

“Her legacy is to ordinary people with a dream, she achieved it,” Robinson Masters said. “And then once she achieved it she moved on, and she didn't give up.”

Sterling described how Walker’s story seems to create its own magnetism the deeper one looks into it.

“Who was this person that had so many different facets to her?” Sterling said. “That you can easily find something to kind of sink your teeth into and go, 'Wait, she was a stunt double in the movies?

“And, ‘Oh, wait, she flew airplanes in this historical all women's derby and knew Amelia Earhart?’

“And, ‘Oh, wait, she mined turquoise and copper?' It’s like there were so many different elements of her life that were just captivating.”

I.B. Walker, the aviatrix’s father, summed up his daughter best in an interview before the arrival of the racers to Abilene. He told the Abilene Daily Reporter how he had worried often about his daughter growing up.

“She could out-ride any man I ever saw,” he said. “I am sure she will come through if knowledge of flying and pure grit count for anything."

This article originally appeared on Abilene Reporter-News: True Grit: Abilene aviatrix flew with grace