I Tried A Supposedly Miraculous Weight Loss Treatment. It Ruined My Life.

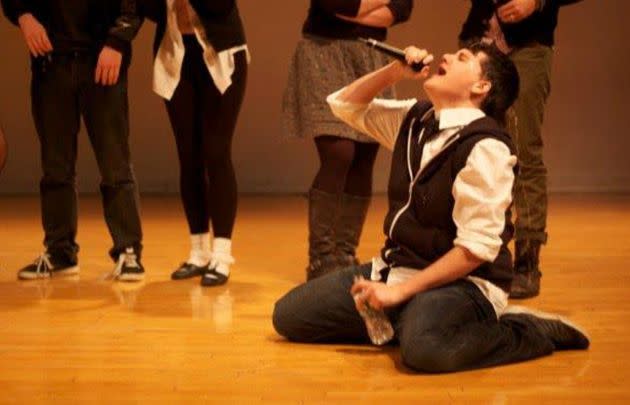

The author before his surgery. "This is when I was at my heaviest," he writes.

The needle the doctor was holding was about the length of my forearm. He was right, I shouldn’t have looked down. I was standing in his office in Glendale, California, my shirt off and my pants pulled down to my ankles. My belly was on full display to every doctor, nurse, assistant and attending that came by and peered in to see the procedure up close. It was 2010 and the lap band was still considered an exciting “miracle cure” for obesity running rampant around Los Angeles. You couldn’t drive down any highway and not catch sight of the “1-800-GET-THIN” billboards.

Gastric band surgery is like putting a rubber band around your stomach. There’s no internal cutting (a big pro), and your stomach remains intact, unlike in a gastric bypass, where the stomach is cut, and intestines rerouted. The lap band sits snugly in the upper curve of your stomach and creates a small upper pouch. Basically, it tricks your body into thinking you have a stomach the size of a pigeon. You eat a lot less and get fuller faster — all of these were big selling points. Of course, my body would need to be tricked. I knew that by that point in my life it wasn’t going to let a single pound go easy.

I was only 19 when I got the band, but I had been put on diets as early as 7. I was tired of being fat, tired of spending my life trained on one single goal and nothing else, tired of waiting for my life after fat to start. So, I let the doctor push a needle into the port behind my ribcage and inject a full cc of saline solution. I felt the sides of the band swell and close my stomach entirely. Slowly he pulled the plunger back and my stomach opened the smallest bit, enough for water or other liquids. I had already lost 30 pounds ― only 80 more to go. Only 80 more until my life could finally be mine.

I didn’t know then that the lap band would not be a portal to a new life. It was just a trap, sold to me for $6,000 ― an eating disorder I bought and now cannot escape.

I got the lap band because a girl was mean to me. OK, that’s the short version. But it’s not untrue. I moved to Los Angeles at 18 years old and 320 pounds. I fell in love with my roommate, who didn’t mind the attention, but never took me seriously as a dating prospect. She didn’t mince words on the subject either: I was too fat. Not too fat to fool around with, but too fat to be seen with, too fat to fall in love with.

The long version is a lot longer. My mother obsessed about my weight and put me on diets throughout my entire childhood. By the time I was 18, I had been to fat camp three times, was a hardcore Weight Watchers member, and could recite to you the basics of every fad diet that had existed from 1997 onwards. I drank cabbage soup, avoided carbs, cut out lunch, had a liquid breakfast, and had a personal trainer two, three, five days a week. No expense had been spared and still I was fat. (One night, when I was at my thinnest, my dad decided over dinner to calculate how much every pound of my weight loss had cost him. It was meant to be a joke, but I don’t think I laughed much.)

The author three years after his lap-band procedure.

We paid out of pocket for the lap band and I qualified based on the BMI requirement ― I was at the far end of the chart in the “why aren’t you dead yet” section. I didn’t need a letter from a therapist or more than one consultation with the surgeon I chose. One down payment, some blood, piss and a CT scan of my insides and I had a surgery day booked. I drank only liquids for 10 days before surgery. I spent them chain-smoking Marlboro Reds and chugging orange juice. I lost my first 10 pounds.

Under anesthesia, I dreamt I was kissing Catherine Zeta-Jones. When I came around, the pain was thick and undulating, pulling my chest in and collapsing the top half off me. It took weeks to walk fully upright again and days before I slept comfortably. It was worth it to me then. I felt myself shrinking and reveled in the compliments that came thick and fast.

I’ll always remember those first few days post-surgery. I lay in bed eating only handfuls of ice chips, popsicles and thimbles of chicken broth. The world felt empty and strange without the ritual of food ― coffee at breakfast, drinks with friends. But it also felt open, new, possible. I didn’t need food anymore. I had beaten it. I would kill every memory of my fat self and start new, with a svelte shining body that everyone would love.

The first thing I puked was an apple. That’s not on the billboards ― the puking. Neither is the potential hair loss or dental damage or symptoms of general malnutrition. The lap band is an actual physical barrier ― it literally stops food from entering the larger part of your stomach. If you don’t chew slowly enough or often enough? Vomit. Things that are too fibrous? Eating too quickly? Or in bed? All of those are going to make food come right back up. And sometimes it would happen if I drank water too fast or ate things that are too cold or too spicy. Sushi, Pizza, and hot dog buns were all a no-go. I’ve puked in trash cans, out of car windows, mid-stride on a date behind a tree, and on the corner of Notre Dame cathedral when I couldn’t help it. But the very first time was an apple.

After I had my band filled with saline (it’s called an adjustment), I was put on an entirely liquid diet. Adjustments started to happen about two months after surgery, once the band had loosened from the initial implant. Saline was injected through a needle into a port behind my ribcage in a humiliating ritual that I then had to repeat every 30 pounds or so. Adjustments were essentially resets ― they closed my stomach to everything but water and broth.

Weeks of broth and prune juice (to try and keep my bowels working) eventually gave way to a soft-food-only situation. As the saline in the band evaporated, the band became looser, and I could try food that a toddler might be able to handle. The sheets that I was given suggested cottage cheese, a plastic-tasting baby food, and sugar-free pudding that gave me the shits. Some nights I would go to a deli and order a side of hot gravy and sip it slowly with a spoon, careful to work every morsel onto my tongue.

The author in 2023.

I soon ignored the suggestions and devoured anything with flavor, getting creative with the word “soft.”

I decided “soft foods” included Whole Foods homemade pico de gallo with crumbles of fancy blue cheese for punch. I sliced fresh avocados and doused them in sweet soy sauce to stop cravings for sushi, ate smoked salmon with lemon juice and a thin spread of cream cheese when I wanted a bagel. I drank miso soup like it was water and obsessed over young Thai coconuts with their delicate flesh and vitamin-packed juice.

Eating at home wasn’t the problem though ― it was going out. Every social event seemed to suddenly revolve around food. It was everywhere ― everything I couldn’t have. At first, I sipped lattes while friends enjoyed cheeseburgers. I reminded myself I was beyond food now. Above cheeseburgers. Months passed and I was starved (literally) for something with bite, with texture. I was losing weight rapidly, new clothes falling off of me just weeks after purchase. Eventually, I stopped buying new jeans and just got a belt that I punched my own holes in when I ran out. I felt like I was constantly under siege ― everywhere watching people eat and drink and live normal lives while I carried bottles of Pedialyte and protein shakes to school so I wouldn’t pass out. Eventually I figured out I could eat what I wanted and then put it all back in the toilet.

I was starving and vomiting. I got used to the vomiting. I got good at the vomiting. I couldn’t do it before the band ― not by myself. Now I knew exactly what would come back up and how fast. I could cock my head back like a pigeon and let a whole meal go. I started eating things I knew wouldn’t stay down. Why not? What did it matter? I was still losing weight. No one cared how it was coming off as long as it kept coming off.

I lost 100 pounds and then about 20 more. And then I stopped getting adjustments. And then I gained 50 back ― and they won’t budge.

The lap band isn’t as popular as it was. No more billboards. Thegastric sleeve is now the most commonly performed weight-loss surgery in the U.S., (a procedure that just cuts out a large part of the stomach and leaves a smaller stomach intact). Though other people may have had success and be entirely happy with their banding experience, it reportedly results in less weight loss than other bariatric procedures and, as of 2019, it accounted for only 0.9% of all bariatric procedures performed in the U.S. With injectables like Mounjaro and Ozempic flooding the market, weight loss surgery might soon be a thing of the past all together.

I get the appeal of a silver bullet. At my heaviest, I would have given a whole limb to be thin, and I mean that literally. But the miracles aren’t real because humans need food. We have to eat. It’s non-negotiable. When I was my heaviest, I was lonelier than I had ever been or would ever be. Life felt like it was happening around me ― to other people. I was stuck on an island, trying hard not to take up so much space. I want to tell you I wouldn’t get the band again, but I can’t promise that. I was so desperate.

The world wants fat people to be desperate, to be apologetic, to be invisible. The body positivity movement may have changed things a little, but we’re still relentlessly searching for the “cure” to obesity. It took me a long time to understand that I didn’t need to be cured. That my body and my belly were doing what they had evolved over centuries to do — to hold weight and keep me alive. No plastic band was going to change that ― not really.

I don’t judge anyone taking these new “miracle” drugs. I wanted that miracle too. I just know now that miracles aren’t real. Your body is, though. And it’s worthy of love, no matter what.

William Horn is a writer living in Boston. You can find him on Twitter @WillsHorn and read everything he’s ever put on the internet here. He’s currently working on a memoir and a book about being a professional fat guy.

Do you have a compelling personal story you’d like to see published on HuffPost? Find out what we’re looking for here and send us a pitch.