Training schemes give new hope to refugees in France

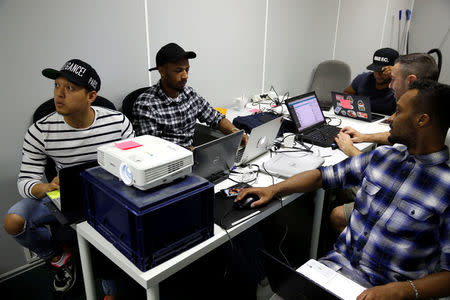

By Gilbert Reilhac and Caroline Pailliez SAINT-AVOLD/MONTREUIL, France (Reuters) - Sudanese refugee Nasser Mudwey has no regrets about giving up his dream to reach Britain, opting instead for a training scheme at a Peugeot gearbox factory in eastern France. Julian Durdur, 23, who fled from persecution against Christian minorities in Iraq, is learning code at a center where low-skilled workers are trained in digital technology, outside Paris. They are part of a 15 billion euro ($18 billion) push by President Emmanuel Macron to make France's training programs more relevant for businesses and lower an unemployment rate that hovers near 10 percent. Hoping to cross to England, Mudwey was holed up in the squalid "Jungle" migrant camp outside the northern port of Calais before it was razed by the government. On the condition that he was literate, he was offered vocational training as part of his rehousing. He chose mechanics. Learning French? Assembling gearboxes? "Nothing is difficult," the former driver who fled war in Sudan told Reuters at the training center near the German border. The HOPE program he is on trains refugees for jobs that companies struggle to fill, as a massive skills mismatch, especially in manufacturing, creates bottlenecks in the recovering economy. HOPE was launched in 2016 and now involves 1,000 refugees. France last year granted asylum to 43,000 people. Refugees have the right to work and claim social benefits, but often struggle to find employment. "CONTAGIOUS SPIRIT" How European Union states share the burden of migrants fleeing war and poverty has divided the bloc. Rights groups have criticized Macron over an immigration bill that tightens asylum rules. Early results suggest HOPE is more successful than previous attempts at integrating low-skilled workers. Only 2 percent of contracts are terminated prematurely, compared with 20-25 percent for traditional training schemes, organizers say. "It was tailored for companies' needs," said Pascale Gerard of national training organization AFPA. "That's the key for success." The program's cost, at 20,000 euros per head, includes housing and food, as well as language classes and counseling. Most of that is financed by the employers. Nearly two out of three trainees have school-grade qualifications or lower. In the Paris suburb of Montreuil, Durdur hunches over a keyboard writing code for a weather forecasting program. "My goal was to come to France to live a life without war, go to school and learn a new culture, get a job," said Durdur, who hopes to follow his eight-month training program with an apprenticeship in web development. Durdur already has a business idea: an app teaching the Aramaic language, his mother tongue. "It's the language of Jesus," he said. "Not many people speak it." The refugees' motivation and work ethic have surprised many of the employers and training officials. "Their positive spirit is contagious," said Smaranda Adina, a manager at a supermarket chain. "Even if these people went through hard times, they have a willingness to succeed." (Writing by Michel Rose; editing by Richard Lough and Robin Pomeroy)