Told her baby was dead, then alive, a Charlotte mother was thrust into a nightmare

LaChunda Hunter was sitting at her dining room table one February morning when her phone rang. It was the hospital.

The doctor on the phone told Hunter that things were looking up for Legacy, the tiny, premature girl Hunter had delivered at Novant Presbyterian nine days earlier.

Hunter said she distinctly remembers what the neonatal specialist told her that morning in 2022: Legacy’s jaundice, breathing and white blood cell count all had improved, and he was “very optimistic” about her condition.

Hunter screamed with joy. Yet her mind could not make sense of it: Three days earlier, a hospital doctor brought her devastating news that Legacy had died.

Hunter’s elation was short-lived. Another doctor called later that day to say that the encouraging test results she’d been provided were for a different baby.

The hospital refused to meet with Hunter or fully explain what happened, she said. And the ordeal has haunted her for more than two years.

In a new lawsuit, she says Novant Health and two doctors were “grossly negligent” in their communications to her — and that she has suffered severe emotional distress as a consequence.

“For the first time in my life, I feel broken,” Hunter said. “I wasn’t raised to be broken.”

Now, she said, she owes it to Legacy to push for an explanation about what happened — and why.

“I’m still being her Mom by fighting for answers,” she said.

Novant didn’t address The Charlotte Observer’s questions about Hunter’s complaints.

Kristin King, Hunter’s attorney, gave Novant written permission to discuss her case with a Charlotte Observer reporter. But Novant said that it would not discuss the case unless Hunter signed a consent form that would allow the hospital to share her private health information with others. King objected to that, calling the release “inappropriate and overreaching for the circumstances involved.”

A written statement from Novant says the hospital system’s neonatal intensive care unit teams develop strong relationships with families.

“From physicians, to nurses, to social workers and child life specialists, open, consistent communication with families is a vital aspect of the care that we provide,” the statement reads. ”While we’re focused on helping our youngest patients grow and thrive, we’re also prepared to help families navigate loss with the utmost compassion and dignity.”

A happy pregnancy

When you enter Hunter’s bright and orderly home in northwest Charlotte, it’s hard to miss the large framed photo of Legacy in the foyer. It was taken days after her birth. At the time it was taken, she weighed just 12 ounces. Her dark eyes are open.

“When you walk in, I feel a part of her is here,” Hunter said.

In 2008, Hunter moved from Virginia to Charlotte and, in time, began working for a family-owned trucking company. She’s preparing to graduate this May from Johnson C. Smith University, and hopes to begin studying family law at Elon University later this year.

She shares her three-bedroom house in Charlotte’s Oakdale North neighborhood with her two adopted children, ages four and 16. Hunter always loved children, she said, and she had long wanted to give birth to a child of her own. But that was a struggle.

After becoming pregnant in 1999, Hunter carried to 32 weeks, but her baby girl was stillborn. She repeatedly tried to conceive after that but her attempts to have a baby weren’t successful.

“I’d given up on having kids,” said Hunter, now 46. “I just thought that it wasn’t in the cards for me.”

But in September 2021, Hunter and her partner, Thomas Gray, were shocked and overjoyed to discover that she was pregnant. She was 43 at the time, but had reason to believe her baby would be OK. Her mother was the same age when she gave birth to her, she recalled.

For more than five months, Hunter’s pregnancy went smoothly, with very little morning sickness. In December, Hunter’s friends and family hosted a gender reveal party at Maggiano’s restaurant at SouthPark Mall.

Hunter had given a close friend permission to learn the baby’s gender before her. And her friend teased her without mercy, saying the color of the dress she wore to the party would reveal the baby’s gender. Then the friend wore a dress that had both pink and blue, forcing Hunter to wait about an hour before the big reveal.

“My family was so happy,” Hunter said. “My church was happy. This baby was a community baby. It wasn’t just my baby.”

By February, Hunter’s hands and feet had begun to swell — a sign of high blood pressure. She was admitted for evaluation at Novant Presbyterian Medical Center on Feb. 11. On Feb. 13, doctors performed an emergency C-section.

At 8:23 am that day, Legacy Darmika-Grace Gray was delivered. Born premature at about 23 weeks, she weighed 12 ounces and was just a little larger than Hunter’s hand. But the toes on her pink feet were always moving.

Hunter was immediately struck by her eyes — ovals topped by arch-shaped eyebrows. They were a miniature version of her father’s.

“She was perfect to me,” Hunter recalled.

Six days of life

The parents named Legacy in honor of Gray’s sister, Darmika Gray, who was shot to death in Charlotte years earlier.

While hospitalized, Hunter visited Legacy frequently at the neonatal intensive care unit, where the baby was connected to a respirator. Legacy would kick her tiny legs when her parents talked to her. The sight of her made Hunter beam.

“She looked amazing,” Hunter recalled. “I just saw a baby who needed assistance breathing.”

On the Friday that Hunter was discharged from the hospital, one of the NICU doctors, Dr. Jay Kothadia, told her he thought Legacy might have a hole in her intestine — a dangerous condition that affects some premature infants. A surgeon said she was too small to be a candidate for surgery, Hunter said, but the baby was given antibiotics.

The following day, Feb. 19, Hunter got an early-morning text from a hospital nurse who said that Legacy was “looking beautiful.” She drove to the hospital with her aunt and uncle that morning to see the baby. Legacy’s eyes were open and she was reported to be responding to antibiotics.

“She didn’t look like she was gravely ill to me,” Hunter recalled. “I mean, she looked like my baby girl.”

From the hospital, Hunter called her pastor, Bishop Kevin Long of Temple Church International.

“I put the phone over the incubator. And he prayed over her,” Hunter remembered. “After that, I was like, ‘She’s covered. We’re good.’ ”

Then, Hunter said, she remembers giving Legacy a message of her own: You’ve been blessed by a bishop. So I know you’re going to fight.

Devastating news

But at 10:38 pm that night, Hunter got a call at home from a NICU doctor who brought gut-wrenching news: Legacy had died.

In disbelief, Hunter immediately checked Legacy’s MyChart account on her phone to find out what happened. That screen previously had been full of information about Legacy’s treatment and condition. But it was empty.

The NICU doctor had invited Hunter to say goodbye to Legacy. So early the next morning, Hunter and two close friends drove to uptown Charlotte. On a hallway inside the NICU, a nurse ushered them into a small dark room without windows, she and one of the friends said. It appeared to be a walk-in closet, they said. It had two chairs and shelves that held baby supplies.

A nurse handed Hunter the body of a tiny baby, wrapped tightly in blankets, with the head and face only partly visible.

In shock, Hunter only remembers crying.

“I was devastated,” she said. “I kept saying to myself, ‘This wasn’t supposed to happen.’ ”

Over the next two days, Hunter grieved as she made arrangements for Legacy’s funeral service and burial.

Two phone calls leave mother in turmoil

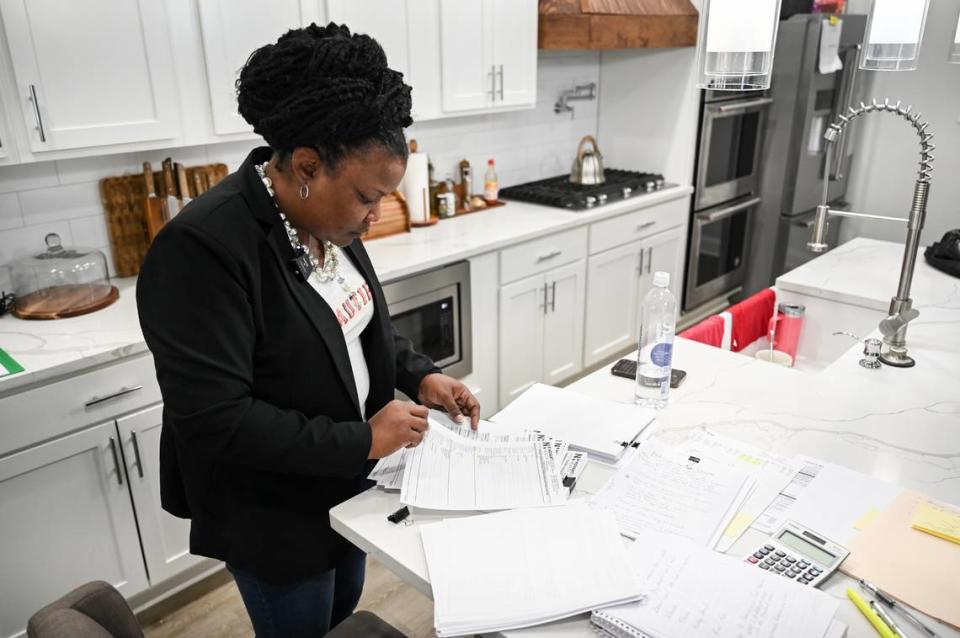

On Feb. 22, three days after being told Legacy had died, Hunter met with a work assistant at home to tell her how to carry on her duties at the Charlotte trucking company while she took time off work.

She was sitting at her dining room table with her assistant that morning when she got a call from the hospital. It was 10:46 am.

Hunter answered the call and put it on speakerphone. It was Dr. Kothadia. He asked if he was speaking to Ms. Hunter, Legacy’s mother.

Then, Hunter’s lawsuit says, Kothadia said something astonishing: He was very excited to share that the baby’s jaundice, white blood cell count and breathing all had improved. Things had really turned around for Legacy, Hunter recalled him saying, and he was “very optimistic” about her condition.

Hunter jumped from the dining room table and screamed. Her assistant, listening by speaker phone, exclaimed: “You told her that her baby was dead!” according to the lawsuit, which was filed on March 5.

Dr. Kothadia immediately hung up, the lawsuit says.

As she recounted this part of her story during an interview at her home, Hunter paused. She placed her hand over her brow. Her eyes began to water.

She remembers the precise words that raced through her mind after that call: “Thank you God! Thank you God!”

Hunter repeatedly tried to call the hospital NICU but no one answered, she said. She eventually reached a nurse. Hunter remembers telling the nurse what had happened — that she’d gotten contradictory messages about whether Legacy was alive or dead, and that she needed to know what was going on. The nurse put her on hold, she said. Then the call disconnected.

Several hours later, she got a call from a different doctor at the hospital — Dr. Preethi Srinivasakumar, Hunter said. The doctor said she was calling to apologize because “the wrong telephone number had been placed on the chart,” and that the test results that had mistakenly been provided to Hunter earlier that day were for a different baby, the lawsuit says.

Shocked, Hunter told the doctor that she needed more information and wanted to see the baby whose test results had been reported, according to the lawsuit.

The doctor told Hunter that if she came to the hospital, she’d be arrested, the lawsuit says. Srinivasakumar became defensive, Hunter recalled, and told Hunter she needed to get a lawyer.

Hunter sat on her living room couch after that call, sobbing and feeling nauseous.

“You told me that she was alive. And now I have to grieve her all over again?” she asked during the interview. “Where’s the compassion?”

Both Kothadia and Srinivasakumar are named as defendants in Hunter’s lawsuit, but neither responded to requests for comment.

Fighting for an explanation

Soon after receiving Srinivasakumar’s call, Hunter hired Charlotte lawyer Kristin King, who said she repeatedly reached out to Novant and its attorney to ask for a meeting to discuss what happened. No one responded, King said.

Instead, a lawyer for Novant promised to have the matter investigated.

“We will review this matter and the allegations of your client’s claim including getting the case reviewed by a relevant expert witness,” Leigh Ann Smith, a Raleigh lawyer hired by Novant, wrote in a March 8, 2022 letter. “This can take some time, sometimes three or more months.”

But Novant never provided further explanation, the results of any investigation “or proof that an investigation had even taken place,” the lawsuit says.

“I feel like they completely overlooked me,” Hunter said. “I might not be prominent in Charlotte but I’m still human.”

In the months that followed, questions about whether Legacy was alive or dead would not leave Hunter alone.

She had so many doubts that she delayed the burial and arranged for DNA testing to confirm that the dead baby was hers. The initial DNA test failed because of problems with the sample. A subsequent DNA test found the sample to be a match.

But time and again, Hunter examined a photo of the dead baby’s body that had been taken at the funeral home. That baby didn’t resemble Legacy, Hunter concluded.

In December 2022, 10 months after Legacy’s reported death, Hunter received what she considers another insult: a bill from Novant for $86,000 for her daughter’s medical care. Hunter had medical coverage through Medicare and Medicaid, but Novant neglected to bill those insurance plans, the lawsuit says.

“You want me to pay you for this?” Hunter asked in an interview. “You want me to pay you for torturing me?”

The hospital also did little to help Hunter obtain Legacy’s medical records, she said.

She had to stand in line and pay for the records, the lawsuit says. The records she initially received in 2023 were incomplete, she said. It took two return trips and multiple calls to Novant’s record-keeping department to obtain the documents.

Living with trauma, unanswered questions

The ordeal continues to torment Hunter, who says she suffers from anxiety and depression and rarely sleeps more than three hours a night. In May 2023, she said, she was diagnosed with PTSD.

Hunter tried to return to her job at the trucking company in late 2022, but found the experience with her baby left her without drive and unable to focus.

Legacy sometimes appears in Hunter’s dreams. In one, a man drove to Hunter’s house in a powder-blue car, opened the back door and let out a toddler with eyes that Hunter would recognize anywhere: It was Legacy.

She and the man walked to Hunter’s front door.

“Why did this happen?” Hunter asked the man in her dream.

“I don’t know,” the man replied.

Hunter and her four-year-old daughter, Eryah, then sat on her living room couch with Legacy. Eryah looked at Legacy with a smile.

“My little sister,” she said.

When one ‘I’m sorry’ isn’t enough

Legacy’s medical records did nothing to clear up Hunter’s uncertainties. The hospital continued to chart information about the baby six days after she had reportedly died, a Novant record reviewed by The Observer shows. The record stated that Legacy’s feeding tube was removed on Feb. 25, 2022 — six days after Hunter was first told that she’d died and five days after she held the infant’s body.

In May 2022, the baby was buried alongside other infants at York Memorial Cemetery. Still wrestling with doubt, Hunter has yet to put a headstone over the spot.

“If she’s still out there, we’ve just missed two years of that beginning,” Hunter said. “And if she’s not out there, my kids just missed two years of me.”

Hunter and her attorney say they hope the lawsuit will spur Novant to improve its policies and practices.

“It’s not enough just to say ‘We’re sorry,’ ” said King, the attorney. “They need to say, ‘This is what happened. This is what we’re doing to try to ensure it doesn’t happen again.’”

Novant Health's statement

Novant Health did not answer The Charlotte Observer's questions about LaChunda Hunter's complaints. On March 7, Novant did send this written statement:

Although patient privacy laws prevent us from speaking to the details of a specific patient’s experience, we extend our deepest condolences to anyone experiencing the loss of a child. Neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) are places of both hope and, unfortunately, sometimes grief as we care for patients facing critical illness and complications from prematurity. Our NICU teams develop strong relationships with patient families and guide them through what is an understandably stressful time. From physicians, to nurses, to social workers and child life specialists, open, consistent communication with families is a vital aspect of the care that we provide.

While we’re focused on helping our youngest patients grow and thrive, we’re also prepared to help families navigate loss with the utmost compassion and dignity. We have a dedicated parents’ space that allows families to stay overnight, and it also serves as a private bereavement room. Helping families honor the memory of their babies is an important part of what we do, and our teams provide commemorative keepsakes in addition to other grief resources. We understand that each family’s grieving process is unique, and we highly recommend KinderMourn as an additional resource to help families find peace and healing.

How lack of transparency at hospitals does ‘more harm than good’ for grieving families