TLH 200: Yellow Jack, the scourge of Tallahassee in 1841

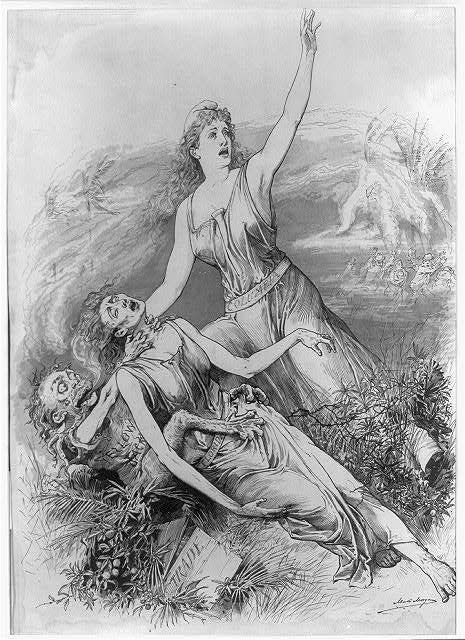

In 1841,Tallahassee faced the scourge of Yellow Jack.

Yellow Jack, commonly known as yellow fever, attacked Tallahassee and the surrounding areas, even making headlines in other states, said Holly Kilgore, a graduate student who studies yellow fever in the history department at Florida State University.

The Bangor Daily Whig and Courier newspaper from Bangor, Maine, states on Oct. 28, 1841: "The Fever has been very severe this season in Florida. At Tallahassee there were forty-five deaths in forty days (from Sept. 3d to Oct. 13th) in a population which can hardly exceed 1,000. The family of Mr. Welford, consisting of a father, mother and three sons, were borne to the grave within a week."

The Welford family's tombstone marker at Old City Cemetery offers a grim confirmation of the report.

Carried by a specific species of mosquito known as Aedes aegypti, yellow fever is believed to have originated in West Africa. The mosquito, and subsequently yellow fever, was carried over to the Americas by the slave trade and has caused between 100,000 and 150,000 deaths over a series of epidemics.

It spread to cities as north as Boston, but after 1822, stayed in the South.

"The environment here is perfect for mosquitoes... very humid, very hot. There's a lot of pooling water, that's important too," Kilgore said.

In North Florida, yellow fever killed thousands of people, including the Territorial Gov. Robert Reid, his daughter and granddaughter, who all died in the Tallahassee epidemic of 1841.

Even the editor of one of Tallahassee’s newspapers, the Tallahassee Floridian, died from yellow fever that year.

In May 1841, Yellow Jack traveled from either Port St. Joe or Port Leon (accounts differ), causing mayhem in Tallahassee by June.

One visitor at the time remarked that the scourge sweeping the still young Florida capital city had "reduced people to walking corpses on the street."

Half of the Tallahassee population had contracted the disease and so many were dying that the city's first cemetery — the still extant City Cemetery near FSU — was established, wrote Democrat writer Gerald Ensley in 1999.

Estimates on the number of fatalities vary from 80 to 400 — either one a significant number in a town whose population varied from 800 to 1,600 depending on the season.

“It was a summer that put a major dent in Tallahassee's image of good times,” Ensley wrote.

From jaundice to delirium to death

Yellow fever isn’t contagious, but it can spread from person to person through the bite of an infected mosquito.

There are three stages to yellow fever. The disease first causes a fever with aches and pains and jaundice.

The second stage, the remission stage, is when the person either gets better or gets worse. If worse, the tell-tale symptoms of yellow fever show up: bleeding from the nose, eyes, gums and mouth; delirium; black vomit and excrement.

"There's no recovery after this. If you hit that third stage and all these symptoms show up, you're not getting better," Kilgore.

If someone survives, they gain immunity for the rest of their lives, a process known in some regions as "seasoning" or "acclimatizing,” Kilgore said.

Thankfully, a vaccine has been available for more than 80 years. Today, people traveling to or living in areas of South America and Africa are recommended to get vaccinated.

How Tallahassee responded to the yellow fever scourge

Yellow fever also dealt a blow to the city's economy.

"Our country has been and still is in a dreadful situation from sickness. You can't imagine our distress," a Tallahassee resident wrote to a friend in Savannah, Ga., in July 1814. "Some of our planters will lose their crops from the sickness of their hands. One of my nephews, working thirty hands, has not one at work."

Francis Eppes was the mayor at the time, and he along with eight councilmen, enacted health regulations to try to prevent the spread of the disease. Germ theory didn't exist yet, so the prevailing thought was that the yellow fever was caused by miasma, or bad air.

Local doctors ordered the city to cut down the weeds in vacant lots. Some residents burned barrels of tar in front of their houses, believing the smoke would ward off the infection.

Eppes and the council required all graves be dug at least 6 feet deep, and all victims needed to be buried within two hours of their death.

"It's a very traumatic moment, emotionally and physically, for the nurses and the family members that witnessed it and then have to take care of the body itself," Kilgore said. "When you have these new restrictions and new guidelines for how to bury your loved one... it's devastating."

Those who survived sought greener pastures lest the yellow fever scourge return. Landowners and those who could afford it moved outside of the city limits and created a community called Bel Air (literally meaning beautiful air). It was two miles south of downtown, near where Monroe Street and Capital Circle meet. The community was abandoned after the Civil War.

“Tallahassee had always escaped epidemics, but there were few places to hide in 1841,” author Julianne Hare wrote in “Tallahassee: A Capital City History.”

In Tallahassee, those who died from yellow fever are buried in several cemeteries in the area.

In downtown, people who succumbed to Yellow Jack lie in graves at St. John’s Historic Cemetery or Old City Cemetery.

On the northeast side of town, there are people buried at Pisgah United Methodist Church. In one part of the cemetery there’s a section of unmarked graves.

An epitaph reads: "In the open area before you are the unmarked graves of approximately thirty former residents of the Centerville community. During the spring and summer of 1841 a yellow fever epidemic raged across northern Leon County. Pisgah church had the only cemetery in the area and was used as a common burial site. Sleep With The Angels."

This story is part of TLH 200: the Gerald Ensley Bicentennial Memorial Project. Throughout our city's 200th birthday, we'll be drawing on the Tallahassee Democrat columnist and historian's research as we re-examine Tallahassee history. Read more at tallahassee.com/tlh200. Ana Goñi-Lessan can be reached at agonilessan@gannett.com.

This article originally appeared on Tallahassee Democrat: TLH 200: Yellow Jack, the scourge of Tallahassee in 1841