How tiny houses built with dirt ‘Legos’ hope to help narrow KC’s home ownership gap

Godfrey Riddle is about to see his vision rise up out of the earth: The first of 44 tiny houses, 600 square feet each, built to give more people a chance to become homeowners. It’s an idea as old as the Egyptian pyramids.

After a year of planning, research, fundraising and development, Riddle is set to build his first tiny house near Montgall Park, on the East Side of Kansas City, this spring. The prototype is planned to be a 600-square-foot house made of compressed earth blocks (CEBs), an environmentally friendly material that will aid in Riddle’s mission of creating sustainable and affordable housing.

Riddle, through the non-profit he founded, Civic Saint, is close to constructing his first tiny house after reaching his financial goal of $100,000 following a recent victory at the National Gay and Lesbian Chamber of Commerce Business and Leadership Conference pitch competition. He walked away with $55,000 in prize money.

“The future of affordable housing is underneath our feet,” says Riddle. “This isn’t really anything new and you see it with the pyramids and the Southwest adobe structures. These houses are likely to stand for hundreds of years.”

According to Riddle, the ecologically friendly earthen blocks are composed of 90% soil, mixed with water and cement. Using these instead of traditional cement blocks or clay bricks cuts costs and is safer for our environment.

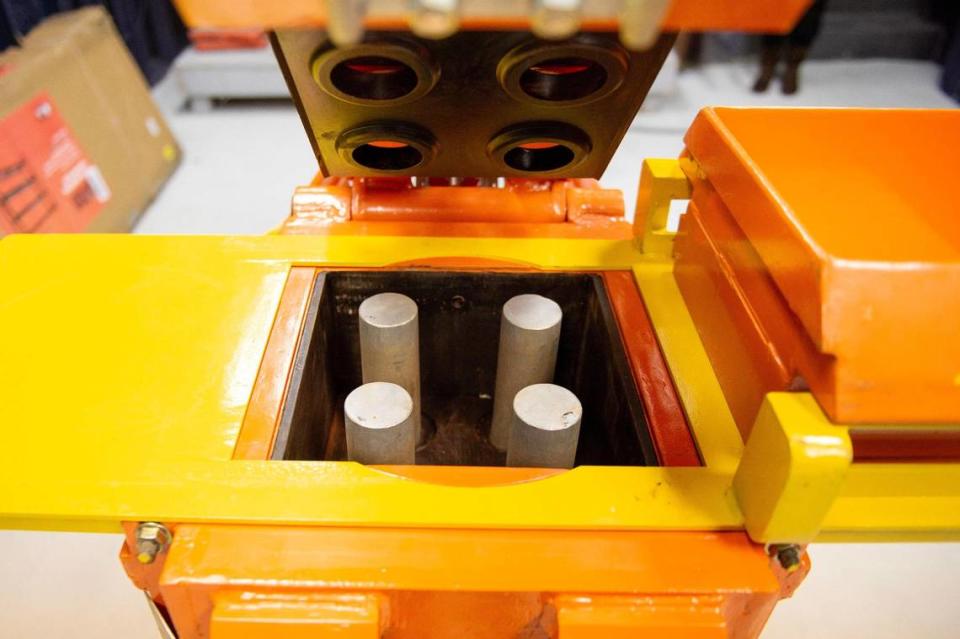

Soil goes into a machine that compresses it into a brick that resembles a Lego block, with holes for stacking and fitting pieces into place. According to Riddle, his blocks have twice the durability of cement or clay with none of the carbon dioxide emissions created by traditional brick manufacturing.

He estimates he can manufacture over 10,000 earthen blocks at his work area in eight hours and erect a tiny house within a week with a team of eight to 10 workers.

Michael Gibson, an associate professor in the architecture department at Kansas State University, thinks that earth bricks are a step in the right direction toward creating more affordable housing options for residents in the metro.

“I think earth bricks are an interesting product and idea,” says Gibson. “I think there is a shift happening in the field of design, that we are realizing scaling back on size will definitely help home ownership and make it more available to people.”

According to Gibson, the production of most compressed earth bricks are a great option for developers who are looking to cut costs on materials while also looking for an environmentally friendly standard for building.

“A material like compressed earth bricks uses very little energy to produce and you are basically just taking soil that comes right from the site unlike with traditional bricks where you have to extract certain clay that are filled with certain characteristics, then you transport that material to where the bricks are fired then those bricks have to be moved on trucks to the construction site, so it takes way more to make a traditional clay brick,” he says.

Gibson said he believes that the biggest hurdle the tiny house initiative will face is changing the mind set of both buyers and builders who believe bigger means better.

“I always say we live in an HDTV world with people who build their aspirations of what their dream home is based on what they see on TV and we need to change the concept,” says the professor who has taught at K-State for 13 years. “I have also found smaller homes are not as profitable for builders to build so we are seeing a lot more luxury homes and apartments that most people are unable to afford.”

Riddle thinks tiny houses could help bridge the racial wealth gap by making home ownership possible for many families who can’t otherwise afford it.

Riddle, 34, studied city planning at the University of Kansas. After graduation he moved to Kansas City from Olathe with hopes of improving housing. Riddle has been acquiring land in areas where rising rents are pricing out current residents.

A Mid-America Regional Council article last year, on housing discrimination using U.S. Census data from the 2020 and 2021 American Community Survey, stated: “In the Kansas City region, Black residents have one-third the housing wealth of white households, lower rates of homeownership and lower home values.”

According to Census Data, in 2021 Black residents, who make up 26% of the population in Kansas City, only accounted for 7.2% of home-owning households.

While Riddle wants to use these homes to impact Black home ownership, he also wants to work in conjunction with local nonprofits to help other groups who may lack the means to become homeowners. Riddle hopes to also help members of LGBTQIA, Hispanic and women’s groups who struggle to find housing they can afford.

“It makes it difficult to rebuild 18th and Vine when developers are buying up all the land to build multi-tiered levels of density and we need single family homes, not just apartments,” he says. “Our units are non-toxic, fireproof, bulletproof, noise resistant and structurally sound so they will definitely be built to last.”

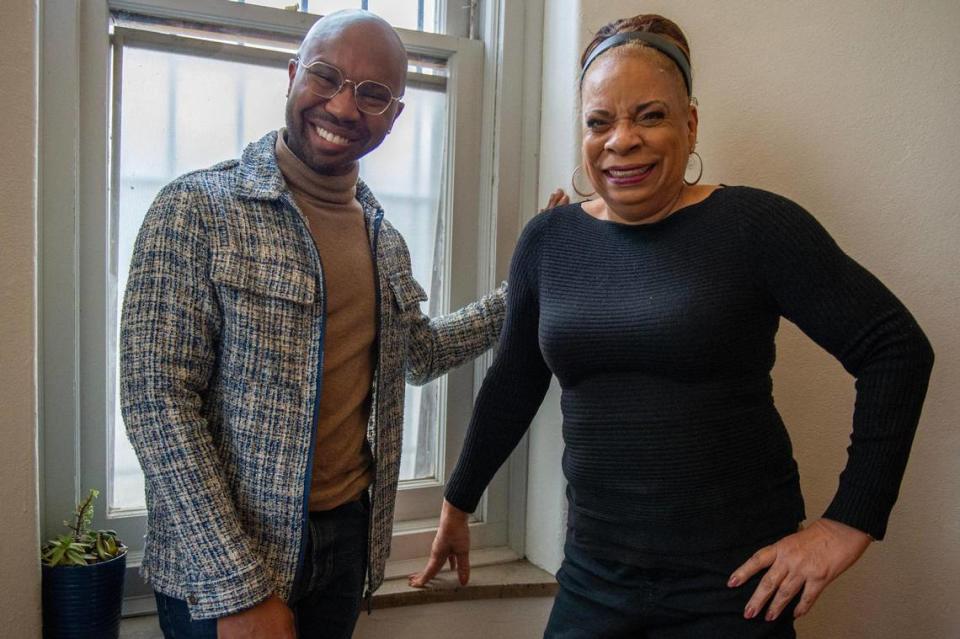

Pat Jordan, founder of iSTEAMkc, a workforce and real world learning organization, has been working with Riddle to get his project off the ground, providing a work area at her offices at 2033 Vine St.

“I have watched over the years as home ownership in the Black community has dropped drastically,” says Jordan. “This area is filled with so many vacant lots that can be used for these developments because most people in the community aren’t going to be able to swing $250,000 to $300,000 they need to buy a newly built home in the area.”

Jordan, who has worked in the Vine Street community for years combating housing inequities, sees Civic Saint’s plan to create housing options as a much-needed resource for residents who may not get a chance to own a home.

“I am all for business integration, but I am not for gentrification,” she says.

Riddle is set to unveil the prototype home during the annual KC Design Week in April, followed by a panel discussion on the housing crisis for Black residents. That event is being held at 2000 Vine St.

With plans to construct 44 tiny houses in his inaugural year, Riddle hopes that Civic Saint’s tiny houses will expand throughout the metro.

“The main idea of what we are doing is to create something that is not only obtainable but sustainable,” says Riddle. “We want to not only make something that will be a steppingstone for Black families becoming homeowners but also create something that will last and is a quality-made structure that a person can call home.”