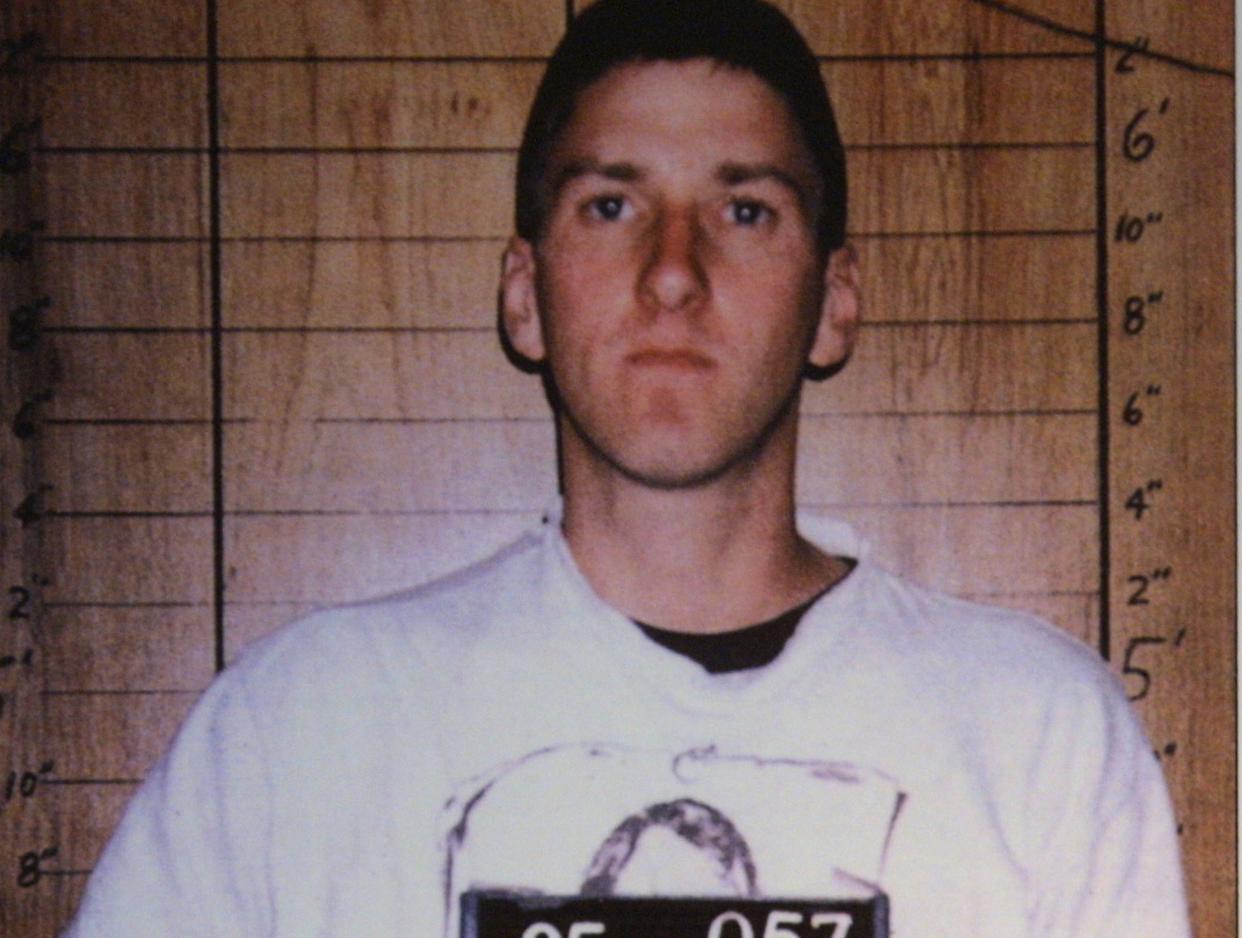

Timothy McVeigh execution: Covering the death of the Oklahoma City bomber

The Independent’s Andrew Buncombe covered the execution of Timothy McVeigh in Terre Haute, Indiana, in April 2001 in a report headlined ‘US executes its Public Enemy No1’

Timothy McVeigh died with his eyes open.

Strapped on to a plastic gurney, his body covered by a sheet, he strained his head to look in turn at the witnesses sitting behind tinted glass, waiting to watch him die. He seemed to nod towards the room where his lawyers sat, apparently at ease.

Then, without saying a word, he lay back his shaven head, settled himself and stared straight towards the ceiling where a CCTV camera was beaming this most public of private executions 620 miles away to Oklahoma City. With all America seemingly paused, McVeigh, corralled behind razor wire and redbrick walls barely blinked as the lethal chemicals were pumped into his body.

Timothy McVeigh, icon of hate and anger, Public Enemy Number One, was executed here early yesterday morning in what was, in effect, a ritual ceremony the US hopes will purge its collective outrage over the worst act of terrorism on American soil. Six years after McVeigh destroyed a federal building in Oklahoma City, killing 168 people, America finally fulfilled a pledge first made by President Bill Clinton.

McVeigh, 33, was pronounced dead at 7.14am local time, just as the sun was warming up and burning off the moisture from the closely mown grounds of the prison where the execution took place. Harley Lappin, warden of the federal penitentiary, broke the news in a simple and formal manner.

“The court order to execute Timothy McVeigh has been fulfilled,” he said, his face grey and drawn. “Pursuant to the sentence of the US district court, Timothy James McVeigh has been executed by lethal injection.” He added, “Inmate McVeigh did not make any final statement.” Instead, in the hours before his death, he had sat in his cell copying out in a neat but rather child-like hand, the words of William Ernest Henley’s 1875 poem Invictus.

The last lines say: “I am the master of my fate, I am the captain of my soul.” Was McVeigh the master of his fate? Those hoping that the “soldier” who talked of “collateral damage”, would finally show remorse, would have been disappointed. Aware that more than 200 bomb survivors and victims’ relatives were watching the CCTV in Oklahoma City, McVeigh tried to “take charge of the room and understand his circumstances”, according to one witness.

McVeigh was brought in shackles into the green-tiled death chamber at 7am, compliant and co-operative. He made no fuss as he was strapped into the plastic-covered adapted dentists’ chair, his body covered in a sheet that came halfway up his chest.

There was one hitch. Ironically in this age of instant-hit technology, the CCTV feed was not working properly. A couple of minutes later, the problem sorted, Mr Lappin announced: “We are ready.” The curtains were drawn back and McVeigh raised his head, strained his neck and tried to look at those who were in the witness rooms.

Mr Lappin turned to Fred Anderson, a US Marshal and the only other person in the death chamber, and said: “Marshal, we are ready. May we proceed?” Mr Anderson called the operations room of the Justice Department, then put down the receiver and replied: “Warden, we may proceed with the execution.” The first of the three drugs was administered through an IV inserted into his right leg at 7.10. The line, coming from another room, jerked slightly as the sodium pentothal started to flow. The other two drugs followed in quick succession. Witnesses said McVeigh’s eyes went glassy, his skin a shade of pale yellow.

And then at about 7.15am, Mr Lappin announced over the loudspeakers, “Inmate McVeigh died at 7.14am.” In Oklahoma City, 232 bomb survivors and victims’ relatives had watched as a wide-screen TV relayed the CCTV feed. “I think I did see the face of evil today,” Kathy Wilburn, whose two grandsons were killed, said afterwards.

It is difficult to know what to make of all this, this surreal conclusion to a process designed to deal with a criminal that America had would have so much preferred to have been a fervent Islamic terrorist rather than a white Roman Catholic from the US heartlands.

What should one think of the manner in which McVeigh was destined to die? Outside the prison, Harold Smith, an anti-death penalty campaigner from Albany, New York, who had been at the same spot for three days, had this view: “It makes a mockery of the words ‘civilised nation’.”