Is it time for new railroad rules? Critics say U.S. train industry is in crisis

Just before he retired, Matthew Rose offered a warning to his peers running the nation’s large freight railroads.

Rose, then the CEO of BNSF, one of the largest American railroads, told an industry conference in early 2019 that railroads were shirking their responsibilities to serve all customers by adopting new business models that focused on only the commodities and routes that delivered the most profits.

Recent industry trends — aimed at pleasing Wall Street investors — would invite more scrutiny from government regulators, Rose warned.

“I really do believe we’re going to get in a lot of trouble by doing that,” Rose said, according to an account in the trade publication Trains.com.

It was a prophetic message.

The business transformation of freight railroads in the last few years has raised the ire of top government leaders who have grown frustrated over the industry’s growing focus on short-term profits.

New business tactics have pushed railroads to build longer trains, which can now block off emergency responders’ access to entire communities. They’ve also slashed work forces, leading to mounting frustration among workers, who narrowly averted a national strike earlier this month.

Industry changes have also led to widespread complaints about poor service from the myriad businesses that rely on rail to move supplies across the country.

U.S. Rep. Peter DeFazio, a Democrat from Oregon, characterized the freight railroads as being at a “point of crisis” during congressional hearings in May.

DeFazio, who chairs the House Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure, said railroad executives had grown addicted to “watching the ticker on Wall Street.” Poor railroad service has caused factories to close, customers to move commodities to less efficient trucks and pushed up costs for consumers, he said.

“The facts are undeniable,” he said. “Freight service in the United States of America — we used to have the best freight rail in the world — is abysmal.”

DeFazio, a frequent critic of the industry, raised his voice several times in an impassioned tirade during a hearing this spring. At one point, he directed his anger toward one of the industry’s top regulators, Martin Oberman, who leads the Surface Transportation Board.

“We’ve got to act more decisively and more quickly and you need to do that,” the congressman said. “You have to protect the railroad network in this country.”

While Oberman strikes a more moderate tone, the STB chairman shares growing concerns about the rising influence Wall Street wields over the nation’s large railroads. He worries what their current performance means for the long-term success of the railroads themselves.

“I do have a sense that the railroads just are pushing the envelope much farther than the long run is in their own self interest,” Oberman told The Star. “This is a bipartisan concern…There is a growing concern in the Congress that things need to shape up.”

The nation’s rail infrastructure is widely viewed as crucial to national security and economic prosperity. That’s why federal law states that railroads “may not refuse to provide service merely because to do so would be inconvenient or unprofitable.”

But, as the former BNSF chief executive noted, railroads have been cutting back service in recent years as they’ve adopted Precision Scheduled Railroading, a business model that seeks to cut expenses and run only the most profitable and efficient trains possible. In effect, railroads are now offering poorer service, critics contend, while raising prices on their customers.

“Monopolists typically cut their output and raise their prices…That’s the easiest way for them to get rich rather than growing output,” Oberman said. “And so that’s what they do. And the pressure to do that comes from Wall Street investors who control the boards.”

Oberman said rail executives should take heed of warnings from experts like Rose.

“The railroads have not listened to that and they’ve kept going. So it’s not unreasonable to see this as, if we’re not at a watershed moment, as approaching such a moment if things keep going the way they are.”

He would prefer railroads fix themselves without government intervention. “I don’t know how to run a railroad. I know what’s not happening, but I don’t know how to go in and run the railroad,” he said.

“But at some point, we exist to protect the public interest. We can’t just sit back and watch these trends go unabated.”

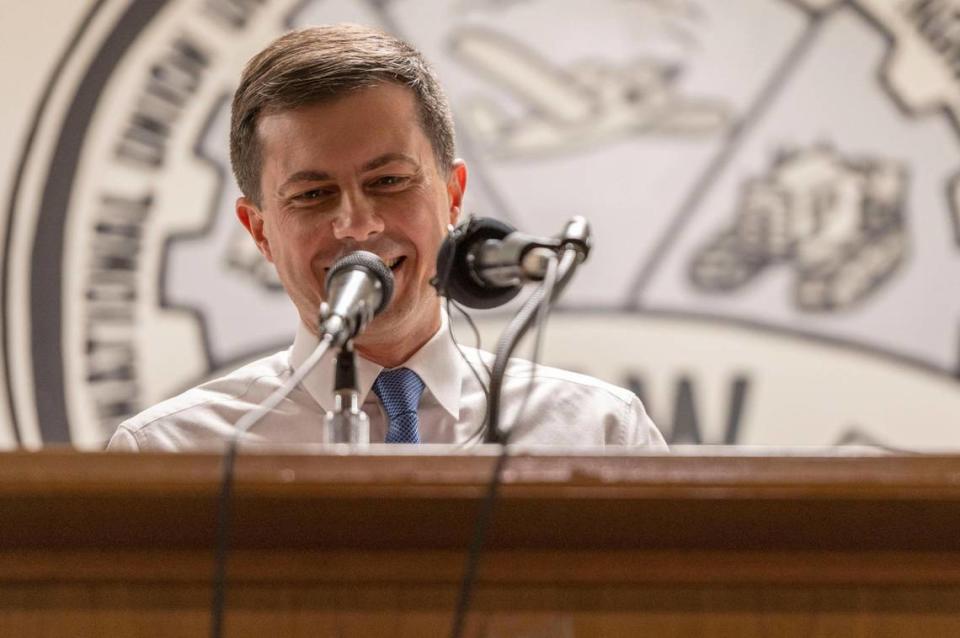

Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg, whose department oversees the Federal Railroad Administration, said he shares Oberman’s concerns. He said the administration must be “very attentive and very hands on” to improve cargo rail.

“And that’s true on everything from making sure that it’s safe, which is of course our primary responsibility, to making sure that freight rail can be compatible with high quality of life in communities that it passes through,” he said Friday in Washington.

The transportation secretary noted that the administration is partnering with railroads to do things like build new grade separations — which separate train traffic from roads and pedestrians. But he said the industry may also need more regulation.

“I think we can include good outcomes for shareholders but what we can’t go on with is shareholders versus the world in terms of who’s benefiting from this business model,” he said.

At stake is not only the longevity of America’s railroads, but the American economy itself. Trains remain the cheapest and greenest way of moving freight. And 30% to 40% of the American economy relies on rail freight, Oberman said.

Major railroads have seen huge losses in one of their mainstays, the shipment of coal to feed electrical power plants and haven’t found new customers to fill those gaps. Instead, they’ve mothballed locomotives and cut routes and staff. That’s concerning for the environment and the economy, particularly at a time when many manufacturers are looking to bring production back to the United States from overseas following the supply chain crisis of the coronavirus pandemic.

“I would say it is a long-term crisis,” Oberman said. “It’s hampering the U.S.’ ability to be successful at home and to compete on the world market. It’s not good and we should not settle for it.”

But the congressional delegation from Kansas and Missouri seemed cautious about proposing new regulations on the industry.

Rep. Sharice Davids, a Kansas Democrat on the House transportation committee, said she’s open to studying problems in rail freight, but would be cautious about adding new rules.

“I’m always wary of us trying to make changes that might have unintended consequences down the line,” she told The Star.

But for some rail issues to finally be addressed, those agencies say it will take congressional legislation. For example, longer and longer trains that idle at public crossings have caused entire communities to become separated from lifesaving first responders. But the agencies in charge of the railroads say they’ll need a new law to regulate how long trains can block crossings.

On worsening railroad service, Sen. Roger Marshall, a Kansas Republican, said he has heard complaints from customers, but he would not commit to any action.

“I’ve had lots and lots of complaints from the ag (agriculture) world the last two years, that we have grain sitting on the ground that need to be taken off to the ports in California, the ports in Texas, Louisiana as well,” he said. “So yes, I think it needs to be examined.”

In the absence of congressional action, the Surface Transportation Board has pushed railroads to improve service problems. It has forced the four largest railroads to report weekly performance metrics to the government to keep closer tabs on how they are serving customers.

In April, the board held hearings over “urgent issues in freight rail service” in which it ordered executives of four of the big seven railroads to attend. In June, the board ordered Union Pacific to deliver corn to poultry farms in the West after its customers complained

”The point has been reached when millions of chickens will be killed and other livestock will suffer because of UP’s service failures,” Foster Farms wrote to the board.

The Association of American Railroads, which includes North America’s seven Class I freight lines, says that new regulation is not needed.

In a statement to The Star, a spokesperson said the industry understands that service is “not at the level customers expect or deserve.” But the association says its members have already undertaken “aggressive measures” to improve service and reliability.

“Current service challenges in no way justify abandoning the proven economic principles that enable the industry to spend more than $20 billion annually in capital investments and maintenance that have helped build the world’s safest, most efficient freight rail service,” the association said.