It’s time to free Black revolutionaries from US prisons

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

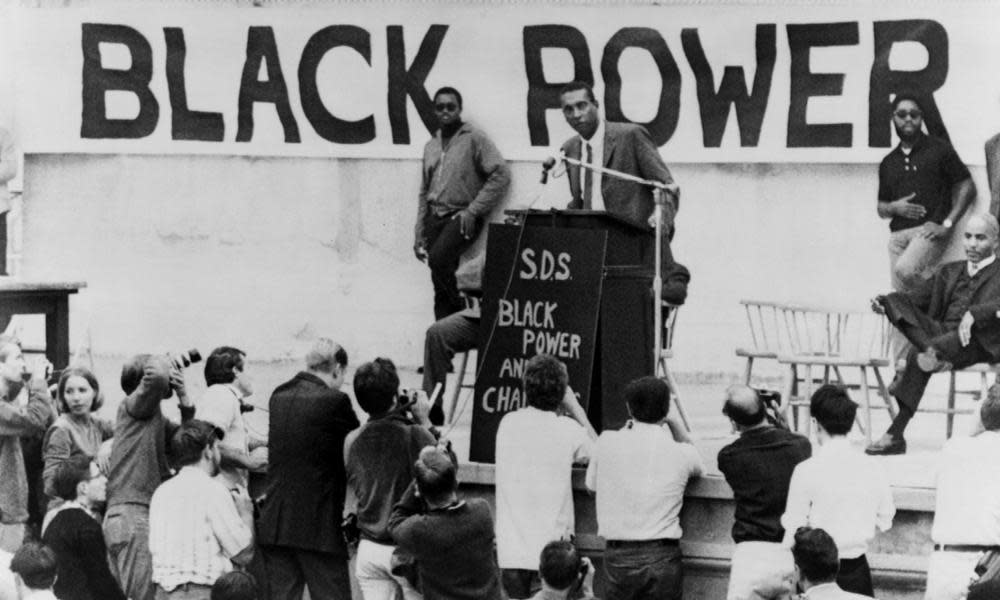

While the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement has increased the profile of holidays like Juneteenth and Black History Month, there is one important Black celebration that remains at the margins of American popular consciousness. Black August is a month-long commemoration dedicated to freedom fighters lost in the struggle for Black liberation, particularly those who were killed by US authorities or who perished behind bars.

Celebrants of Black August view crimes committed by some of these revolutionaries as acts of war against a system already at war with them. With the release of movies like Shaka King’s biopic of the assassinated Black Panther Party leader Fred Hampton and data showing that a large number of Americans now see individual acts of police violence as part of a larger racist system, the politics and culture behind Black August are becoming increasingly mainstream. If new generations of Americans can understand the war that was waged against Black radicals, and against Black Americans as a whole, they should honor Black August by demanding the release of the radicals still incarcerated in a racist system.

Black radicals within the California prison system created Black August in 1979. While it partly commemorates events like Nat Turner’s 1831 rebellion against slavery and the beginning of the Haitian Revolution, it primarily honors the legacies of Black freedom fighters who were imprisoned or killed in the 20th century while working toward revolution in the United States.

On 1 August 1978, Jeffrey Khatari Gaulden, a Black radical imprisoned since 1967 for assault with a deadly weapon, was seriously injured during a football game at San Quentin state prison. The prison staff did not provide fast enough emergency care, and Gaulden died what witnesses considered a preventable death. His death was the immediate impetus for the creation of Black August, but the tradition was also created to celebrate other 1970s Black radicals such as the Jackson brothers.

The elder Jackson brother, George Jackson, was a Marxist-Leninist theorist and organizer who was killed by guards while leading a prison uprising. The younger Jackson, Jonathan Jackson, was shot and killed while trying to kidnap a judge and prosecutor from a California courthouse. Other revolutionaries that Black August sought to honor included WL Nolen, a comrade of George Jackson who was killed by guards after getting caught in a prison fight between Black leftists and neo-Nazis. Two other Black men were also shot and killed in the same incident.

Mama Ayanna Mashama, a founding member of the Black August Organizing Committee, explained how participants observed the first Black August:

… the brothers did not listen to the radio or watch television, additionally, they didn’t eat or drink anything from sun-up to sundown; and loud and boastful behavior was not allowed …

Today the tradition – spread by one of Mashama’s other organizations, the Malcolm X Grassroots Movement – is celebrated inside and outside prisons. Observants engage in reflection, political education, physical exercise and other means of sharpening their bodies and minds to honor the work done by those who came before them. But Black August is also a time to escalate the fight to release inmates who many activists and organizers consider political prisoners.

Mumia Abu Jamal, often just called Mumia, is one of the best-known Black political prisoners in the United States, but far from the last still behind bars. Mumia is a journalist and former Black Panther convicted of the murder of a Philadelphia police officer in 1981. The evidence and witness testimonies against him have long been disputed, and an international movement has sprung up in his defense. The movement challenged his initial death sentence and continues to fight for an end to his current life sentence. Many organizations, like the Coalition to Abolish Death by Incarceration, view the life sentences of Mumia and other imprisoned radicals as long, drawn-out, deliberately cruel de facto death sentences.

Russell “Maroon” Shoatz, another former Black Panther, was sentenced to life imprisonment in 1972 after being convicted of murdering a police officer. He spent 22 years of his imprisonment in solitary confinement, sitting in a small cell for 23 hours a day, with lights shining above him at all times.

A third former Panther, Albert Woodfox, was released in 2016 from a Louisiana prison after spending 43 years in solitary confinement. While these punishments may seem just for the alleged crimes, casting judgment on them without reflecting on the context in which the prisoners were incarcerated would do a disservice to reality itself.

It is easy for Americans to understand and support Black revolutionaries in other contexts, whether foreign or cinematic. Nelson Mandela, for example, is revered by many Americans. Yet Mandela was hardly different from his American counterparts. He co-founded uMkhonto we Sizwe (Spear of the Nation), an armed group that engaged in bombing campaigns and targeted attacks across South Africa, killing dozens of police, soldiers and civilians in the process. Despite the efforts of the US government, which tried to prop up the apartheid government of South Africa for much of its history, most Americans now understand that the regime was indefensibly premised on segregation and racial violence.

How difficult is it to understand the same for the US for most if not all of the 20th century? George Jackson witnessed the murder of his friend by prison guards for the crime of fighting white supremacists. Mumia had long been targeted by Philadelphia police for his reporting on Move, a Black leftist organization with a compound in the city. A few years after Mumia’s arrest the Philadelphia police dropped explosives on the Move home, killing 11 people, five of them children. The Black Panther Party was harassed, infiltrated and attacked, and law enforcement agents murdered an early Panther leader, 19-year-old Fred Hampton, as he slept in his bed.

A new generation of Black political prisoners languish in prison cells for the crime of engaging in resistance against mass incarceration and police violence

These imprisoned leaders were striving to build a better society for their people at a time when their friends and compatriots were being murdered in their homes. And it is inhuman to let former radicals who are now elderly and sick die behind bars so many decades after they were initially convicted.

Yet this is not an issue solely for Black elders; a new generation of Black political prisoners, such as Joshua Williams, languish in prison cells for the crime of engaging in resistance against the modern state of mass incarceration and police violence, a system that allowed police officers to evade responsibility for killing 12-year-old Tamir Rice in a park, and seven-year-old Aiyana Stanley-Jones while she slept in bed. Williams, arrested at 18, received an eight-year prison sentence for setting fires in and around a convenience store while protesting against the death of Antonio Martin, an armed 18-year-old Black man killed by a Missouri police officer a few months after Williams protested against the killing of Mike Brown by another Missouri police officer.

In the same way mainstream America has tended to embrace Black art while rejecting Black people, mainstream American culture has belatedly embraced the iconography and achievements of Black radicals while leaving them to die. As Levi’s celebrates Black Power with a line of jean jackets, Democrats mimic a style popularized by Black radicals, and Beyoncé’s Black Panther-themed Super Bowl still lingers in the public imagination, we must face the truth.

Black radicals have helped clarify the reality of the systemic and direct violence of the American state, and for that clarity, the nation owes the likes of Sundiata Acoli, Joseph Brown, Veronza Bowers, Mutulu Shakur, Imam Jamil Abdullah Al-Amin, Ed Poindexter, Fred Burton and many others their freedom.

Akin Olla is a contributing opinion writer at the Guardian