This is what I want my friends to do if they have COVID-19 symptoms and are asked to go to the ER

Ashita S. Batavia, MD, MSc, is a board-certified infectious diseases specialist and public health expert with extensive experience in treating epidemics. She works at Lawrence Hospital NYPH-Columbia. (Instagram: @ashita_batavia)

_____

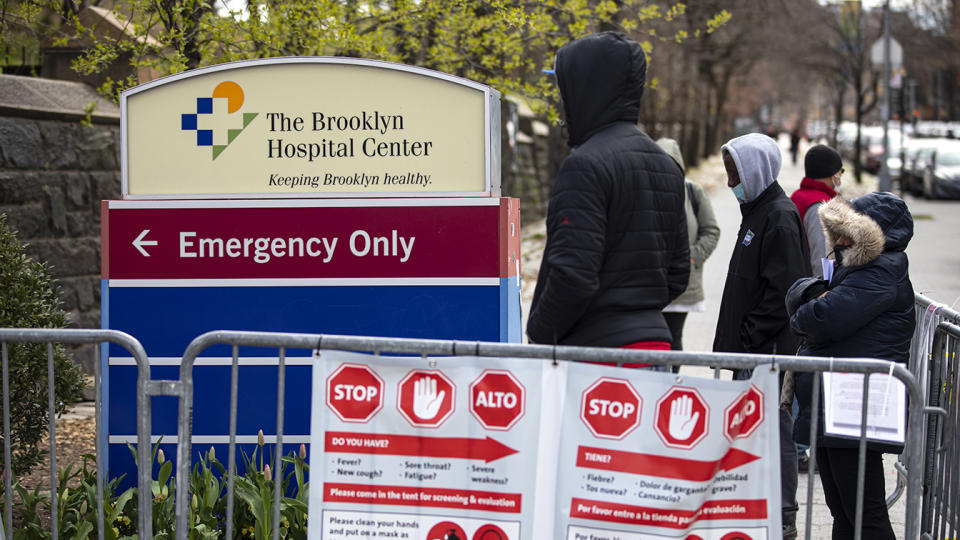

Nearly 400,000 Americans have been diagnosed with COVID-19. In my state, New York, our hospital systems are being strained in unprecedented ways. As a frontline infectious diseases doctor, this is what I want my friends and neighbors to do if they have COVID-19 symptoms and are asked to go to the emergency room.

If you think you have COVID-19, please call your primary care doctor. If you are having trouble breathing, call 911 or go to the nearest emergency room.

1. Bring more than one hard copy of your current medications

Bring a list of all the medications that you routinely take, including the dose and the number of times you take it each day. Let us know if any of these medications were started in the last three months or if your dose was recently changed by your doctor. Unfortunately, we cannot quickly or easily access records from different hospital systems. Having this information on hand can save us valuable time.

Also, if you recently went to urgent care or another ER, please bring any records you were given. If you were prescribed medications, such as a Z-pack (azithromycin, an antibiotic), your doctor will ask how many pills you were able to take.

If a doctor or nurse takes your medication list, please remember his or her name. Unfortunately, in a busy ER your list could be misplaced or forgotten in the pocket of someone’s white coat if they are pulled into an emergency.

2. List your allergies on your medication list

In addition to the name of the medication, it is important to know the reaction. For example, if you take drug X, do you get a rash or have difficulty breathing?

Some side effects, such as vomiting or loose stools, may be mistaken for an allergic reaction. If a drug that causes side effects could help you, the benefits may outweigh the risks. Your doctor will discuss this with you, and you should feel comfortable asking lots of questions.

3. Write down the phone number for your emergency contact

In New York, two major hospital systems have barred visitors unless a patient is giving birth. Being in a hospital can be unsettling, especially if you are alone.

On my last shift, my patient, an elderly gentleman with COVID-19, wanted to tell his daughter that he was feeling better after getting oxygen and medications. He couldn’t call her because his phone battery died and he didn’t know her number. Locating a charger in a busy emergency room isn’t easy. Now more than ever, we want you to be able to reach your loved ones.

Not to mention, your doctors need to know who they should call with updates on your condition or in the event of an emergency.

4. Tell us what you want in an emergency. This is also called your code status.

I have seen that COVID-19 is an unpredictable and dangerous disease. In the hospital, patients who are doing well can suddenly deteriorate. It is important that we understand your wishes in the event of an emergency.

Do you want to be resuscitated if your heart stops? If you can’t breathe on your own, do you want to be intubated — put on a ventilator that will pump air into your lungs? This requires inserting a tube into your trachea, through your mouth. You will require sedation and will be unable to speak, and may be semiconscious for the duration of the procedure, which in the case of COVID-19 may be several days or even weeks. We advise patients to say either yes or no to both questions.

If you choose to have everything done, you are “full code.” The alternatives are “do not resuscitate” (DNR) and “do not intubate” (DNI).

5. Extra credit — disease-specific information that is helpful for treating COVID-19

Every person is different, and medicine is not one-size-fits-all. Your primary care doctor knows valuable information about your health. If your doctor asks you to go to the ER and you have one of these diseases, you can ask them for this information and provide it to the doctors at the hospital.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): Your baseline oxygen level, also called your O2 saturation.

Hypertension: Your blood pressure on your medications. Or, if for whatever reason you do not take medications, your average blood pressure.

Kidney disease: On routine blood tests, your doctor checks your creatinine level to see how well your kidneys are functioning. If you get dialysis, it is important for us to know when you were last dialyzed.

Heart disease: Ideally, we would like a copy of your last ECG or echocardiogram report. Whether or not you have kidney disease, it helps us to know the creatinine level from your last blood test.

_____

Click here for the latest coronavirus news and updates. According to experts, people over 60 and those who are immunocompromised continue to be the most at risk. If you have questions, please refer to the CDC’s and WHO’s resource guides.

Read more: