There's bad news in good news about education | George Korda

“Good-news” stories spotlighting public school academic improvements may have effects that are both good and bad.

On the positive side, it’s good news when results show improvement in what locally, statewide and nationally has been a sub-par achievement record for many years. On the negative side, good-news stories may cause people to conclude that everything, including the kids, is all right.

But everything isn’t, and they’re not.

Teachers must be among the most frustrated people alive. They’ve gone into teaching because they want to help propel kids into personally rewarding futures. But teachers are continually dealing with a never-ending chain of new programs, policies and practices meant to improve educational outcomes. However, for educators in the trenches, the more things change, the more they pretty much stay the same.

TCAP results for Knox County students have improved, but just a little

The Tennessee Comprehensive Assessment Program is a primary state education evaluation measurement. A Knox News story from July 19, 2023, headlined “Knox County Schools students, overall, outperform their peers statewide on TCAP tests,” contained this data: “About 41% of Knox County students across all grades met or exceeded expectations in the reading portion of the annual TCAP test compared to 38% statewide. In math, 33.8% Knox County students across all grades met or exceeded expectations, just above statewide percentage at 33.7%.

“For both reading and math, the results inched up a little from last year. Science and social studies also showed small improvements.”

Such percentages wouldn’t be cited as a significant achievement in most areas of life. Imagine a hospital advertising that its diagnostic tests are correct 41% of the time, or a police department announcing that it solved only 33% of its cases. However, such education news isn’t new news in Knox County, the state of Tennessee or across the country.

The Nation’s Report Card is a component of the National Assessment of Educational Progress. In 2022, Tennessee eighth-graders’ reading scores showed not much difference over decades: “The percentage of students in Tennessee who performed at or above the NAEP Proficient level was 28 percent in 2022. This percentage was not significantly different from that in 2019 (32 percent) and in 1998 (27 percent).”

Nationally, the historical vs. present-day data isn’t encouraging: “The average reading score for 13-year-old students in 2023 was not statistically significantly different from the average score in 1971, the first LTT (long-term trend) reading assessment year.”

In Knox County, standards have been set higher, which makes meeting them harder

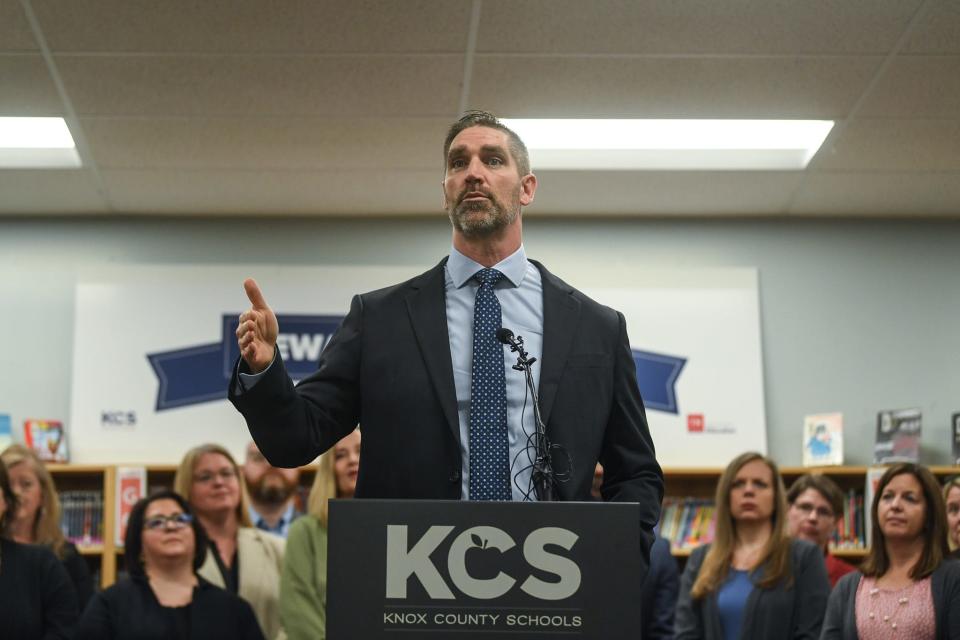

In 2022, after Dr. Jon Rysewyk became Knox County Schools superintendent, he began making a number of changes. There is evidence of academic progress. At the same time, there have been shortfalls in self-imposed goals. It means the system is setting higher standards, and that’s a good thing. Meeting the standards is harder.

There’s plenty of blame to go around for weak performance, and, as discussed in an earlier column, many Americans go around blaming everyone (else) they think is responsible. But all the data in all the reports by all the educational authorities cries out that honest-to-goodness, results-changing progress will come when parents or guardians fully insert themselves into their children’s educational lives.

Practical ways parents can support their children's education

Inserting themselves doesn’t mean only showing up at Board of Education meetings to complain that schools aren’t doing the job of teaching their kids. It means monitoring what their kids are reading – to make sure they’re reading – and reading with them. It means helping them set high personal goals, encouraging them to reach those goals and not relenting when the kids complain and buck like rodeo broncos. It means taking phones and video games away from kids until or unless they show they’ve mastered what they’re supposed to be learning in school. It means working with teachers, not expecting teachers to do all the work.

The benefit? Bolstering a child’s ability to think and to compete in a 21st-century economy. The cost of failure? It’s all around us, in children quitting school, chronic absenteeism or graduating from high school functionally incapable of being of value to an employer. They’re sentencing themselves to failure.

Of course, many parents struggle with a variety of life problems: they’re too tired, too stressed, and it’s too hard to try to corral their kids into improving their academic skills. Too many kids seem to think that someone else will provide for them throughout their lives. Young people exposed to a popular culture that glamorizes being cool over being intelligent may resist and fight to maintain their mediocrity.

When parents see or hear that schools are “making progress,” it’s natural to want to think, or hope against hope, that the job is getting done. But, in large measure, it’s not. That’s why though good-news stories ought to be told about public school academic improvements, they can mask serious problems.

In the end, the stories don’t change student outcomes. The shortest, least expensive and most effective way to achieve higher outcomes for kids is for the adults responsible for them to get on the schooling bus and not just ride, but help drive. That would be good news.

George Korda is a political analyst for WATE-TV, hosts “State Your Case” from noon to 2 p.m. Sundays on WOKI-FM Newstalk 98.7 and is president of Korda Communications, a public relations and communications consulting firm.

This article originally appeared on Knoxville News Sentinel: George Korda: There's bad news in good news about education