When then-Senator Harry Truman tried to find out what was going on in Oak Ridge, Hanford

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The following idea for this "Historically Speaking" column and much of the content comes from C. Mark Smith, a friend in Hanford, Washington. In addition to his information about Hanford, he provided some information I had not previously known regarding precisely how the Manhattan Project got started.

Let me share that with you first:

“The potential for splitting the atom to create unknown amounts of energy had been discovered by European scientists in the years leading up to World War II. Before the start of the war in September 1939, a number of these scientists, many of them Jewish, fled to England and the United States to escape antisemitism in Europe. They carried with them an overriding fear that Nazi Germany would develop an atomic bomb.

“Among those who came were the renowned German physicist Albert Einstein and three Hungarian counterparts, Leo Szilard, Eugene Wigner, and Edward Teller. On August 2, 1939, they drafted a letter, signed by Einstein, and addressed to President Franklin Roosevelt, warning of the potential of atomic bombs and urging the United States, not yet a combatant in the war, to develop the technology before the Nazis. The letter was delivered by Alexander Sachs, a financier, former New Deal administrator, and one of the seemingly endless numbers of unofficial advisors to the President.

“Sachs met with Roosevelt in the later afternoon of October 11, 1939. Rather than reading Einstein’s letter, Sachs delivered a long verbal presentation he had prepared.

“The President, weary after a long day of dealing with the war in Europe and other pressing issues, told Sachs that while he found the information remarkably interesting, government intervention at that point was premature.

“Sachs, calling on his long friendship with the president, invited himself to breakfast the next morning. This time, he told the story of how the American inventor, Robert Fulton, had been rebuffed by Napoleon after offering to build a fleet of steamships that would enable the emperor to invade England. Napoleon had simply been unable to envision ships without sails. British historian Lord Acton later wrote that if Napoleon had shown more imagination, the history of the nineteenth century would have taken a vastly different course.

“After hearing the story and Sachs’ concluding argument, Roosevelt remained silent for a few minutes and then summed up the meeting, Alex, what you are after is to see that the Nazis don’t blow us up?’

“’Precisely,’ Sachs replied.

“Roosevelt called for his military aide, General Edwin ‘Pa’ Watson and, handing him Einstein’s letter, said, ‘Pa, this demands action.’”

The following events occurred as a direct result of this decision summarized from C. Mark Smith’s research paper:

Watson created a small advisory committee that met on Oct. 21, 1939.

$6,000 was authorized to purchase uranium and graphite for experimentation.

Germany invaded France, Belgium, and the Netherlands in May 1940.

Roosevelt replaced the Uranium Committee with the national Defense Research Committee and expanded military research into radar, synthetic materials, and various methods for separating the atom.

Germany attacked Russia in June 1941. On June 28, 1941, Roosevelt issued an executive order that folded the National Defense Research Committee into the newly created Office of Scientific Research and Development. The former Uranium Committee became the Uranium Section and was soon renamed the S-1 Section or Committee.

In July 1941, Great Britain created the MAUD Committee to oversee the British nuclear program.

In August 1941, MAUD Committee member Mark Oliphant, while in the United States, realized the Americans were not aware of the MAUD Committee findings. He briefed the S-1 Section.

On October 9, 1941, Vice President Henry Wallace obtained President Roosevelt’s permission to explore the cost of building facilities to build an atomic bomb.

By Nov. 27, 1941, the S-1 Section told President Roosevelt that fission bombs could be ready in three or four years if all possible effort could be spent.

On Dec. 6, 1941, The S-1 Committee met to begin planning.

On Dec. 7, 1941, Japan attacked Pearl Harbor.

On Dec. 11, 1941, Germany declared war on the United States.

President Roosevelt authorized the development of the atomic bomb on Jan. 19, 1942.

President Roosevelt authorized research on all five technologies at the same time that were thought to be possible to creating an atomic bomb. Those five technologies were, electromagnetic separation gaseous diffusion, thermal diffusion, and creating plutonium by nuclear reactors moderated by heavy water and graphite.

The Manhattan District of the US Army Corps of Engineers was created on Aug. 13, 1942, to oversee the creation of the atomic bomb.

Gen. Leslie R. Groves was named to lead what became known as the Manhattan Project on Sept. 17, 1942.

On Sept. 19, 1942, he issued orders to purchase nearly 60,000 acres in East Tennessee.

On Nov. 25, 1942, he approved purchase of 54,000 acres in Los Alamos County, New Mexico.

By mid-December 1942, the site criteria were established and on Dec. 22, 1942, 670 square miles was selected along the Columbia River in Southeastern Washington state.

Gen. Groves confirmed the decision on January 16, 1943.

On Feb. 9, 1943, Under Secretary of War Robert P. Patterson authorized the purchase of more than 400,000 acres of land in southeastern Washington.

Not even the Joint Chiefs of Staff were informed of the existence of the Manhattan Project. Any newspapers publishers who seemed to be interested were told not to publish anything because of national security. Only the small group of individuals directly involved were aware of it.

Meanwhile, in March 1941, a special bipartisan special committee was created by Congress to investigate problems of waste, inefficiency, and war profiteering during the rapid building up of war production before World War II.

Harry Truman served as a senator from Missouri from 1935 to 1945 and chaired this new committee that came to be best known as “The Truman Committee.” Here is a link to a video describing a new book, "The Watchdog: How the Truman Committee Battled Corruption and Helped Win WWII": https://www.levin-center.org/harry-truman-and-the-investigation-of-waste-fraud-abuse-in-world-war-ii/

Quoting C. Mark Smith again, “in 1940, Missouri Democrat Harry S. Truman was re-elected to the United States Senate. However, he had not been endorsed by, nor did he endorse Franklin Roosevelt,

“A former county judge, Truman soon heard stories of needless waste and profiteering from the recent construction of Ford Leonard Wood in his home state. He was determined to find out for himself what was going on. He travelled approximately 10,000 miles from Florida through the Midwest, visiting military installations and uncovering a litany of fraud, waste and inefficiency in the acquisition and construction of military bases. When he returned to Washington, D.C., Truman met with Roosevelt, who seemed sympathetic, but did not want Truman to reveal the wasteful nature of his administration’s programs.

“Beginning with a shoestring budget, the Truman Committee would become one of the most successful congressional committees in history, ultimately saving an estimated $10-15 billion in military spending and the lives of countless U.S. servicemen.”

It is not surprising that elements of the Manhattan Project and the ever-increasing spending after Gen. Groves was put in charge would come to the attention of such a committee watching for inefficiencies. Initially, the frustration of the people in Hanford who were having their land taken surfaced through congressional representatives and ultimately made its way to the Truman Committee.

By April 1943, it seems the Truman Committee became aware of both the Hanford and Oak Ridge portions of the Manhattan Project. C. Mark Smith details how the Hanford situation of complaints by the landowners caused that, but I have not been able to determine the exact date or method by which the Truman Committee became aware of Oak Ridge.

However, in "The Decision to Drop the Bomb," by Len Giovannitti and Fred Freed, on pages 27 and 28, is found the following section about Oak Ridge and the Truman Committee.

“On one occasion investigators of the Truman committee were stopped at the gates of the Oak Ridge plant, which was producing uranium 235, the fissionable material for the bomb, and a call was put through to General Groves in Washington for instructions. Groves was unavailable and his administrative assistant, Mrs. Jean O’Leary, took the call.

“She said, ‘The security officer at Oak Ridge told me that members of the Truman committee wanted to enter the plant and find out what was going on. The security officer asked for orders from General Groves. I told him the General could not be reached. He said, ‘But, what should I do? They’re waiting at the gate and insisting they have Congressional approval to enter.’ Something had to be done. In the absence of General Groves, I decided to make the decision. There could be only one as far as I was concerned. My instructions had always been that the bomb was of the utmost secrecy. I was to tell no one about it. As far as I was concerned even President Roosevelt would no learn about it from me. So, I said to the security officer, ‘Make up any excuse you want, but don’t let them in.’

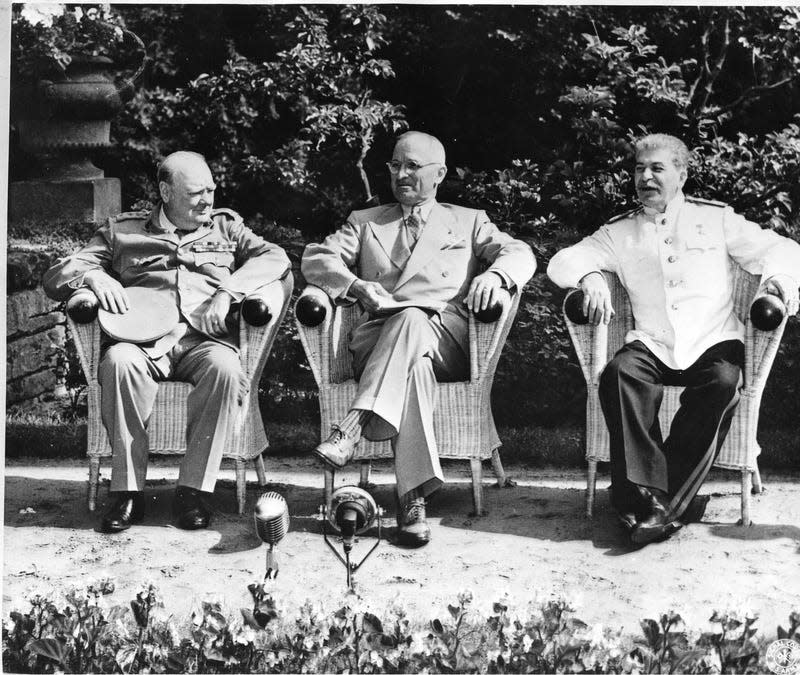

“Truman had then gone to see Stimson (Secretary of War) to protest. On Stimson’s desk was a folder but he did not show it to Truman. Instead, as Truman remembered, he said: ‘I can’t tell you what it is but it is the greatest project in the history of the world. It is most top secret. Many people who are actually engaged in the work have no idea what it is and we would appreciate your not going into those plants.‘”

“Truman agreed to take Stimson’s word that the work going on in the plants at Oak Ridge was of major importance. He did not ask to know more about it, and he called off his investigation.”

Nothing more was done regarding Oak Ridge, but Hanford continued to be troublesome. In December 1943, Truman sent his personal assistant, Fred Canfil to Hanford. He was stopped at the gate on Dec. 7, 1943, and phone calls made to General Groves who insisted that Canfil not be given access. Canfil then sent Senator Truman the following wire, “That no senator, or anyone connected with the Senate was to be given any information about the project.” An interesting side note: It was Senator Truman’s personal friend, Fred Canfil who would later give President Truman the sign that sat on his desk, “The Buck Stops Here.”

While the attempts to investigate Hanford continued, no one was ever allowed past the gates. Even Sen. Compton I. White of Idaho attempted. but was also detained and questioned for about four hours “under bright lights in a windowless room.”

Eventually, a secret background briefing was provided to key leaders of the House of Representatives on Feb. 18, 1944. When Sen. Truman heard about the briefing, he attempted again to open a formal investigation that was quickly rejected citing a mandate from President Roosevelt.

Problems with Hanford continued to surface because of the land acquisition issue until eventually Gen. Groves took action to remove a major troublemaker, Norman Littell, who was the head of the Justice Department’s land division and believed the Army’s appraisal of the land was too low. Ultimately, President Roosevelt fired Littell.

To what extent Sen. Truman learned about the Manhattan Project is not really known. He was not told of it by President Roosevelt when he was vice president, however, James Byrnes did speak to him of an explosive “great enough to destroy the whole world,” while he was vice president.

He did get briefed very soon after becoming president. In his memoirs, he recalled Secretary of War Henry Stimson speaking to him about an urgent matter, “an immense project that was underway – a project looking to the development of a new explosive of almost unbelievable destructive power.” And the next day, James Byrnes gave him all the details of the Manhattan Project that he had known from President Roosevelt.

Of interest is the fact that President Truman never hesitated to use the atomic bombs to help end the war. He never responded to the many questions about that decision except to say it was a military decision to use the most effective weapon available and that it saved many lives by helping to hasten the end of that awful killing war. When asked about his most difficult decision, he replied, “Engaging in the Korean War!”

City of Oak Ridge Historian D. Ray Smith writes "Historically Speaking," which appears in The Oak Ridger weekly.

This article originally appeared on Oakridger: When Harry Truman tried to find out what was going on in Oak Ridge