The Republican Party can’t steal what Trump didn’t earn

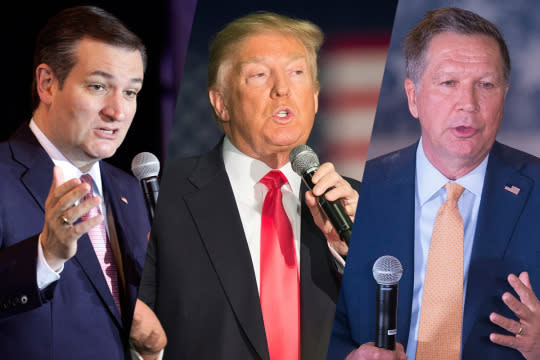

If Donald Trump doesn’t lock down the nomination before the convention, would the party elite plot to install Ted Cruz or John Kasich instead? (Photo: Getty Images)

Finally, it’s here!

Every four years, as predictable as Bill O’Reilly hawking his own books under the guise of viewer mail, the leading prognosticators in my industry dream aloud of a contested convention. It usually goes something like: If Hillary Clinton wins the South and Bernie Sanders wins the Midwest, and then California splits off from the mainland and sinks at sea, and then nine superdelegates have heart attacks and die on the same day … we really could be headed for a second ballot, at least!

We get that you get how pathetic this is, but understand: Orchestrated conventions are like corporate-sponsored gulags. Old-timey straw hats, floor managers barking out urgent orders, giant placards bashing in the heads of rival delegations — this is our desert mirage, the image that sustains us through all the months of drudgery. It’s the only thing we ask of John King and his Magic Wall of Wishes.

And here we are at last. Because after Ted Cruz’s resounding win in Wisconsin Tuesday, it seems that Donald Trump and the leaders of his party — or at least the party he has decided to acquire for purposes of this campaign — are likely headed for a death match in Cleveland in July, from which only one (or neither) can emerge intact.

But wait, you say. What if Trump doesn’t win the necessary delegates but comes within a handful of locking down the nomination, as he very well might? Would the party elite really huddle in some smoke-filled luxury suite, with enraged Trump supporters screaming below them, and plot to install Ted Cruz or John Kasich, or maybe even Paul Ryan, instead?

The answer is no and yes. No because you really can’t smoke in a luxury suite these days, which is just another reason America never wins anymore. And yes because that’s exactly what Republican leaders will try to do, and if you understand the reason political parties were put on earth, then you shouldn’t be surprised.

Or as Kasich put it when we talked about the possibility of a contested convention a few weeks ago: “Why are people hyperventilating about that?”

Some quick history might be useful here. Up until about 40 years ago, voters in both parties had only a limited say in choosing their nominees. That is, a bunch of states held binding primaries and caucuses, but most did not; the main value of the voting process was that it gave powerful convention delegates a good sense of which candidate could get himself elected.

Neither Dwight Eisenhower in 1952 nor Richard Nixon in 1968, the last two Republican presidents nominated under this system, showed up to their respective conventions with the requisite number of delegates in hand. Eisenhower’s nomination was particularly bruising (it involved a fight over the seating of two Southern state delegations that opposed him), and he needed a couple of tries on the convention floor to get it done.

Beginning with the Democrats after 1968, and followed quickly by the Republicans, both parties then shifted to what we know as the modern nomination process, where virtually every state allows its voters to select a slate of delegates. Every triumphant Republican candidate since 1980 has locked down the nomination before the convention. It’s still possible Trump could get there, too, or at least very close.

But nomination contests aren’t plebiscites, and conventions aren’t horseshoes. Close doesn’t actually entitle you to anything.

The decision still rests with the delegates, as it always has, and if Trump can’t convince a relative handful of uncommitted delegates to get him over the top, then there’s something deeply flawed about his candidacy. (Well, yeah.) That’s not a case of being cheated out of what’s yours; that’s just failing to secure what you didn’t really have to begin with.

Or to put this another way: Telling the party it has to nominate you because you have almost the delegate count you need is like telling the lottery commission that you deserve the Powerball payout because you’re only one number off.

But hold on, you might say. What about the will of the electorate? If Trump has a clear plurality of voters, wouldn’t it be stealing to swing the nomination to someone else? Wouldn’t Americans lose all faith in the process?

All of which gets to the heart of what’s dysfunctional about our political system right now.

Fifty years ago, you could have made a pretty compelling case that the clear choice of a primary electorate, even if that candidate didn’t clear the delegate threshold, reflected the will of some broad swath of Americans. When Eisenhower was elected, we were a nation of party members. About three-quarters of the country self-identified as either Democrats or Republicans, according to data from the Pew Research Center.

For decades now, however, as Americans have become ever more estranged from clubs and civic organizations and ever more suspect of politics, we independents have accounted for the fastest-growing bloc of voters. According to the most recent data, almost 4 in 10 voters decline to affiliate with a party, and self-identified Republicans make up only 23 percent of the electorate.

(That’s roughly the same percentage as in the dark days just after Watergate, when joining the Republican Party was like signing up to get Legionnaires’ disease.)

Of those voters who still identify themselves in partisan terms, an ever smaller number actually participate as activists or even as perennial primary voters. Which means that, increasingly, any primary process can be effectively overwhelmed by a highly motivated subset of voters who bear little resemblance to the electorate as a whole.

The job of a political party, though, isn’t simply to validate the vote, to lend itself out as a vehicle for whatever uprising has suddenly taken hold in its ranks. Parties exist to advance agendas, to enact policies, to attain and hold power. They exist, in other words, to win.

Trump doesn’t really adhere to any governing agenda, and a mountain of polls suggest that he repulses a strikingly high percentage of voters.

If Trump arrives in Cleveland with 1,237 delegates, then he’s earned the nomination, without having resorted to subterfuge or even having tapped his own fortune, and Republicans are stuck with him anyway. But if that number tops out at 1,236, then you can bet the party’s leaders will explore their options.

Maybe that means swinging their support to Cruz, who’s more viable than Trump only in the same sense that American is a more viable option than United; either way, you’re going to pay a steep price for the baggage. Or maybe the delegates declare a reset and try to impose a nominee like Kasich or Ryan — just to see if Mitt Romney’s head will explode.

Whatever the plan, it would be hard to blame Republican leaders, assuming they still exist somewhere, for trying. It’s not just their right to avail themselves of the rules if they think they can save the party from a looming disaster. It’s their responsibility, too.