The Last 100 Days: Theologian-in-Chief Edition

Ever since the administration of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, presidents have been judged on the successes they notch during their first 100 days. Now, as Barack Obama ends his historic turn on the political stage, Yahoo News is running The Last 100 Days, a look at what Obama achieved during his consequential presidency, how he navigates the struggles of his last months in office and what lies ahead for him after eight years filled with firsts.

In this 15th and final installment, we look at Obama’s religious rhetoric.

_____

Over the course of his presidency, Barack Obama has spoken about his Christian faith arguably more often and in greater detail than any other modern U.S. president.

That claim will surprise many political liberals who still believe that George W. Bush spent his time in the White House trying to turn the United States in a theocracy run by evangelical Christians. It is also sure to outrage those conservative Christians who argue that Obama is hostile to their faith. And it must confound the 43 percent of Republicans who as recently as the fall of 2015 told pollsters they still thought Obama is Muslim.

But a look back through eight years of Obama’s National Prayer Breakfast speeches, his remarks at the White House Easter Prayer Breakfast that began as a new tradition during his first term, and the heartbreaking number of eulogies he has delivered following mass shootings reveals a president who has spoken about faith not only with great frequency but also with uncommon depth.

“This is a president who is very comfortable with deep reflection and discussion around the theological implications of faith,” says David Domke, communications professor at the University of Washington and co-author of “The God Strategy: How Religion Became a Political Weapon in America.”

Previous presidents have certainly invoked religion and displayed a comfort with the language of faith. Dwight Eisenhower is still the only president to have written a prayer that he read at his first inauguration. He was baptized not long after. And he once said of himself, “I am the most intensely religious man I know.” Several decades later, Jimmy Carter taught Sunday school at a Baptist church not far from the White House during his presidency. George W. Bush cited Jesus as his favorite political philosopher in an Iowa debate before the 2000 GOP caucuses, and he enthusiastically made the support of faith-based organizations one of his first domestic policy priorities.

Bill Clinton may come the closest to Obama in being a president whose speeches occasionally veered into sermon territory. At one point during the 1992 campaign, Clinton traveled to Memphis to address the annual Church of God in Christ convention. Dissatisfied with remarks his staff had drafted, Clinton tossed them aside and delivered an extemporaneous sermon on the “new covenant” between government and citizens, drawing “amen”s from the crowd.

If Clinton sometimes aspired to be the preacher-in-chief, however, Obama has been a theologian-in-chief. Since entering the White House in 2009, he has steadily built on the work of Reinhold Niebuhr, the influential theologian he once told New York Times columnist David Brooks was “one of my favorite philosophers.” And as racial tensions at home and terror attacks abroad have spread anxiety, the president has spent the past few years developing a theology of faith in the face of fear.

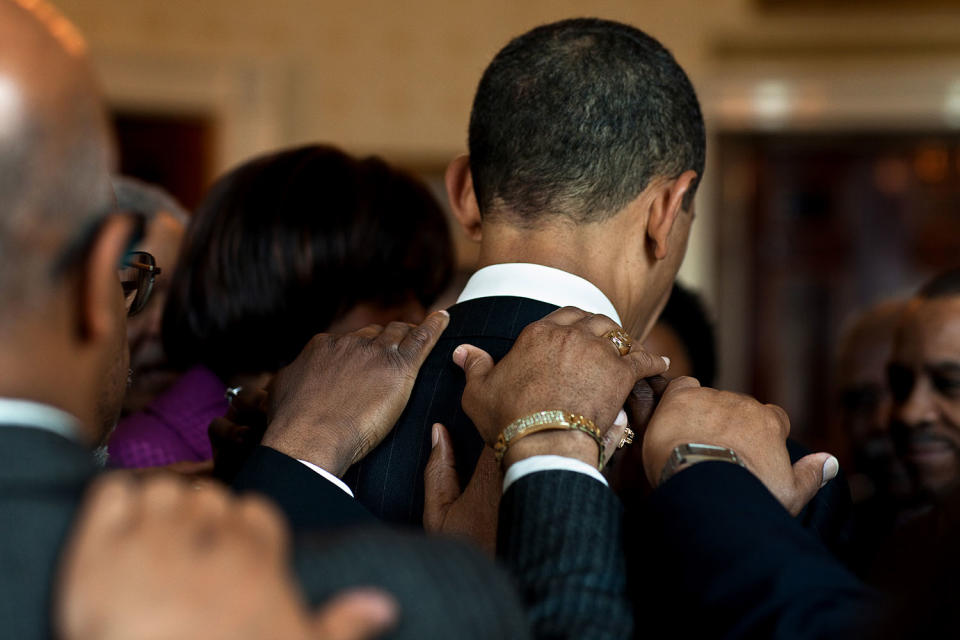

![“President Obama leads a prayer before hosting Thanksgiving dinner [in 2016] for family and friends on the State Floor of the White House.” (Photo: Official White House Photo by Pete Souza)](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/lgEFUspzlsdwLZUS5B81NA--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTY0MA--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/homerun/feed_manager_auto_publish_494/10e3dd7171e58bd81e8cd2e4b2234e34)

Let’s get this out of the way first: Yes, Obama is a Christian. Raised in a mostly secular environment — his mother was “spiritual” but suspicious of organized religion, and his grandparents were nonpracticing Protestants — he began attending Trinity United Church of Christ in Chicago after he moved to the city to become a community organizer.

He responded to an altar call in 1988 at age 26, knelt before the cross and became a Christian. As he told the National Prayer Breakfast in 2011, “It was through that experience, working with pastors and laypeople, trying to heal the hurting wounds of neighborhoods, that I came to know Jesus Christ for myself and embrace him as my Lord and Savior.”

To little fanfare, in 2010 Obama and his close aide Joshua DuBois began a tradition of hosting Christian leaders at the White House for an Easter breakfast. At these gatherings, which continued through the last year of his presidency, Obama spoke in surprisingly intimate ways about the nature of his faith.

“We are awed by the grace [Jesus] showed even to those who would have killed him,” he told the clergy at that first 2010 breakfast. “We are thankful for the sacrifice he gave for the sins of humanity. And we glory in the promise of redemption in the resurrection.”

At the 2015 breakfast, the president spoke about the daily challenges of faith. “Today we celebrate the magnificent glory of our risen Savior,” he said. “I pray that I will live up to his example. I fall short so often. Every day I try to do better.”

Just a few months later, after the killings at Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, S.C., Obama stunned mourners when he began singing the first verse from “Amazing Grace” while eulogizing victims of the massacre. It was a powerful moment. But while that may have been a first for a sitting president, others have spoken openly about their faith. Where Obama differs from his predecessors, according to Domke, is his willingness to go deeper in talking about theological ideas.

“In those moments of high-profile eulogies, he has been pretty comfortable with diving into some of the deeper areas of how faith can comfort and sustain people,” says Domke. “Obama didn’t just sing ‘Amazing Grace.’ He preached about the meaning of grace.”

Indeed, Obama took the extraordinary step of weaving a mini-sermon about the responsibilities of grace into a funeral address. “According to the Christian tradition,” he began, “grace is not earned. Grace is not merited. It’s not something we deserve. Rather, grace is the free and benevolent favor of God.”

He continued, “As a nation, out of this terrible tragedy, God has visited grace upon us, for he has allowed us to see where we’ve been blind.” That hymn reference allowed Obama to segue into the sins the Charleston slaughter forced into the open: pain caused by the Confederate flag; the still-festering wounds of slavery and Jim Crow; and racial inequalities in the criminal justice system. And once again, “the unique mayhem that gun violence inflicts upon this nation.”

Whenever individuals make “the moral choice to change,” Obama suggested, “we express God’s grace.” The message left unsaid: to fight moral change is to refuse to embody grace.

In the last year of his presidency, Obama has turned his attention to the question of how people of faith should respond to fear. Speaking at the White House Easter breakfast in the aftermath of terror attacks in Brussels, he told his guests, “These attacks can foment fear and division. They can tempt us to cast out the stranger, to strike out against those who don’t look like us or pray exactly as we do.”

But, he continued, “if Easter means anything, it’s that you don’t have to be afraid. We are Easter people, people of hope and not fear.”

In Obama’s eulogy for former Israeli Prime Minister Shimon Peres in September, he argued that it is not naive to choose not to give in to the temptations of fear. “[Peres’] pursuit of peace was never naive,” he said. “Every Yom HaShoah, he read the names of the family that he lost [in the Holocaust].” But, he added, Peres “knew, better than the cynic, that if you look out over the arc of history, human beings should be filled not with fear but with hope.”

Obama’s most complete mediation on fear took the form of his final National Prayer Breakfast address, in which he preached on a verse from 2 Timothy: “For God has not given us a spirit of fear, but of power and of love and of a sound mind.”

It did not escape the attention of his listeners that the February 2016 address took place against the backdrop of the Republican presidential primary — and particularly Donald Trump’s candidacy. While Obama did not mention politics, his words served as a rebuke to those who would stoke fear.

“It is a primal emotion — fear — one that we all experience. And it can be contagious,” he acknowledged. “For me, and I know for so many of you, faith is the great cure for fear. Jesus is a good cure for fear.”

“His love,” Obama continued, “gives us the power to resist fear’s temptations. He gives us the courage to reach out to others across that divide, rather than push people away.”

That’s a message that hasn’t been heard from many pulpits in the past year, with conservative Christians afraid of government and threats posed by immigrants and refugees, and liberal Christians afraid of Trump himself and the normalization of intolerance. But it’s a profoundly Christian message — “My faith tells me that I need not fear death; that the acceptance of Christ promises everlasting life and the washing away of sins,” Obama reminded his listeners.

He moved on to argue that being free from fear should lead Christians to be more open, not closed and defensive, protecting their own turf. “Each of us is called … to assume the best in each other,” the president said, “and not just the worst.”

Obama closed with a remarkable tale that took on added resonance since Trump had begun musing about barring Muslims from entering the U.S. or creating a registry of Muslim Americans. The story was about a U.S. sergeant in World War II whose soldiers were captured by Nazis. When the Nazi colonel ordered Jewish POWs to identify themselves, the sergeant responded by telling all 200 of his troops to line up. Holding a pistol to the sergeant’s head, the German ordered, “Tell me who the Jews are.” The American simply repeated over and over, “We are all Jews.”

“I can’t imagine a moment in which that young American sergeant expressed his Christianity more profoundly than when, confronted by his own death, he said, ‘We are all Jews,’” said Obama. “For God has not given us a spirit of fear, but of power and of love and of a sound mind.”

Obama’s approach to religion as president has been in keeping with everything else we know about him. It makes sense that the former professor would respond to years of almost unbearable violence — he delivered at least 10 national addresses following mass shootings in the space of seven years — through reflection on faith and grace and belief.

In his last such appearance — after five Dallas officers were killed by a sniper — Obama quoted from the Epistle of John and the prophet Ezekiel. “My faith tells me these men did not die in vain,” he told mourners.

The son of two secularists was also the first president to regularly mention nonbelievers, starting with his first inaugural address in 2009: “We are a nation of Christians and Muslims, Jews and Hindus, and nonbelievers.”

The man who spent part of his childhood living in Indonesia and whose sister Maya identifies with Buddhism has opened up the White House for celebrations of many faiths. He is the first president to host a celebration of the Hindu holiday Diwali by lighting a diya in the Oval Office. Obama continued an annual White House tradition that has been in place since 1996 of holding an iftar dinner to observe the end of Ramadan. And he is the first president to host a Passover seder for family, friends and staff every year of his presidency.

And the man who spent his entire presidency having his Christian faith denied by critics who suggested he was hiding a secret Muslim identity has consistently spoken out on the need to protect Muslim Americans from discrimination.

It may be that Obama’s willingness to embrace people of other faiths, his broadening of the official religious landscape beyond just white Christian traditions, make it difficult for so many Americans to hear him when he speaks about his own faith.

“He doesn’t fit the white Christian American model,” says Domke. “And at the same time, the remobilization of the right under the banner of the tea party led to a focus on Islam as a threat to Americans. The defense of America as a place that’s friendly to Muslims” — Obama’s statement about rejecting discrimination against Muslims got the loudest and longest ovation in his farewell address last Tuesday — “has been seen as coded hostility to traditional Christian views.”