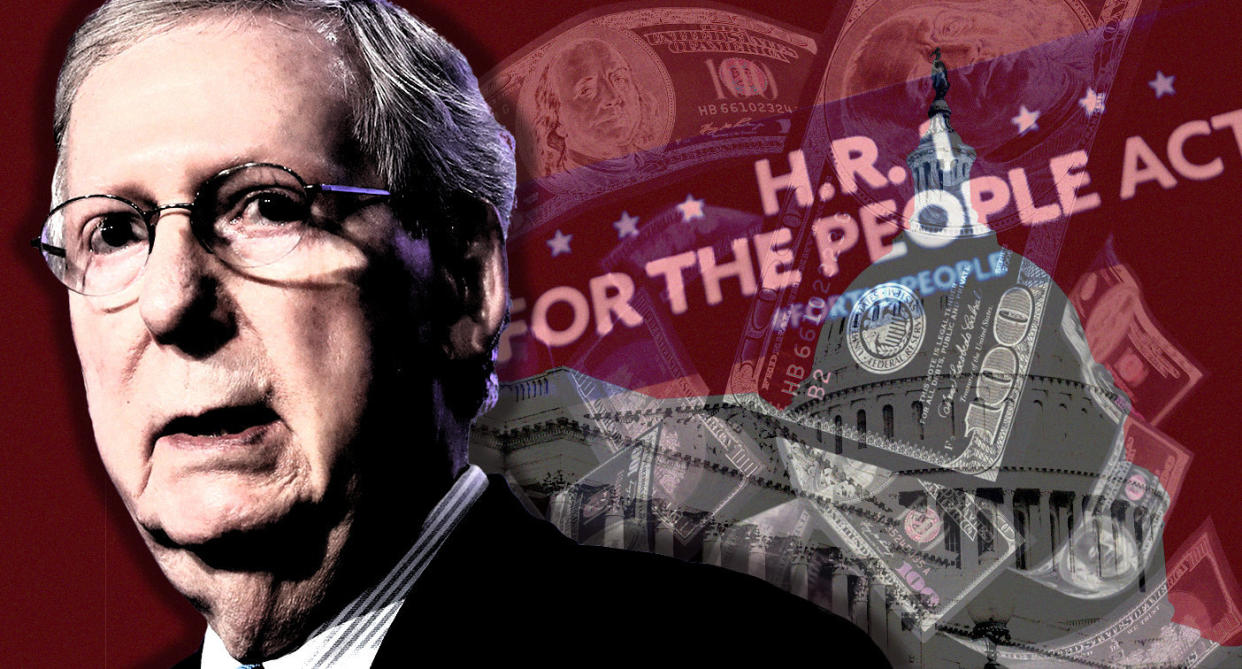

The battle over 'dark money' is back

Lost in the debate over the House Democrats first major bill was a provision that is easy to overlook but would have a huge impact on the role of money in politics.

Democrats passed a sprawling bill on March 8 that would make a seemingly minor change to a federal agency that many Americans don’t know much about: the Federal Election Commission. The bill would reduce the number of commissioners from six to five in a bid to end the gridlock Democrats believe has blocked enforcement of laws designed to limit “dark money” — money from anonymous donors — from pouring into campaigns.

Democrats say the FEC has been rendered useless over the last decade, since a block of three Republican commissioners began voting against enforcement at the same time that the Supreme Court’s 2010 decision in Citizens United v. FEC opened the floodgates to dark money.

Democrats, watchdog groups and some Republicans say that there are now effectively almost no rules when it comes to the influence of money in politics, because with an even number of commissioners, there is no way to move forward if Republicans at the agency always oppose attempts to enforce the law.

This state of paralysis has persisted for some time, but when Democrats retook the House of Representatives in last fall’s elections, they put the issue among their handful of top priorities to change.

The For the People Act passed the House on March 8, but Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., has promised he will not allow a vote on the bill in the Senate. Among a series of speeches he delivered denouncing the Democrats’ legislation, a number were devoted to criticizing the proposed changes to the FEC.

“Since Watergate, the commission has been a six-member body so neither party can use it to punish political opponents. Apparently, Democrats have grown tired of playing fair. This bill would weaponize the FEC with a 3-to-2 partisan makeup,” he wrote in a Washington Post op-ed.

One of the primary ways that the FEC has had authority to compel more disclosure is by penalizing political groups — such as super-PACs — that take a clear side in their elections advertising but have claimed to be “social welfare” or “issue advocacy” groups so that they can qualify as a 501(c)4 group, which is not required to disclose its donors. Groups that conduct more than 50 percent of their ads on political messages for or against candidates must disclose their donors.

For example, in 2014, the FEC deadlocked along partisan lines on a proposed investigation into the conservative group American Action Network, which has been among the biggest dark money groups, after a watchdog group brought a complaint alleging the organization spent 66 percent of its roughly $27 million budget on political advertising from 2009 to 2011.

In 2016, the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia found that the FEC’s dismissal of the case was contrary to law and sent it back to the agency. But the FEC deadlocked a second time, prompting the court once again, in March 2018, to find the FEC’s action contrary to law.

A separate court case last fall forced super-PACs to disclose their donors, but now dark money donors have begun to simply give money to those groups through a different vehicle: limited liability companies, which are often “tantamount to black boxes” when it comes to discerning funding sources, according to reform group Issue One.

McConnell has been a fierce ideological opponent of campaign finance reform for decades, after undergoing a political conversion early in his political career on the issue. Nearly 50 years ago, McConnell — who is now 77 — was the young chairman of the Jefferson County Republican Party in Kentucky. He wrote an op-ed in 1973 comparing the role of money in politics to “a cancer” and advocated for government financing of political campaigns.

“Clearly, public financing at least for presidential elections is an idea whose time has come,” McConnell wrote.

But after running his own election for the U.S. Senate a decade after writing that, McConnell changed his view. “I never would have been able to win my race if there had been a limit on the amount of money I could raise and spend,” he wrote in his memoir.

Since then, McConnell has been known as a tactician who leaves ideological debates to others, except when it comes to money in politics, which is one of the few policy debates that gets his blood boiling. For him, political donations are the equivalent of speech, and to limit giving in any way is to violate the First Amendment’s free speech clause.

Democrats see this as a clever ruse giving cover to a more cynical political motive.

Part of McConnell’s opposition to limits on campaign spending also comes from his belief that the news media is inherently tilted in favor of Democratic candidates and against Republicans, giving Democrats an abundance of free media, a former aide said. McConnell believes Republicans need an ability to get their message out through paid advertising.

McConnell has been a force in the FEC debate since he became Republican leader over a decade ago.

In 2008, three new Republican commissioners arrived at the agency and began voting as a bloc against enforcement actions, according to a former Democratic commissioner, Ann M. Ravel.

One of the new Republican commissioners was Don McGahn, who later became White House counsel to President Trump. Ravel speculated that McGahn and the other Republican commissioners blocked enforcement at the behest of McConnell, who had become the Republican leader in the Senate just a year earlier.

Presidents appoint FEC commissioners, but they are confirmed by the Senate and presidents have traditionally deferred to Senate leaders of both parties as to whom they should appoint.

Republican commissioners have denied any coordination, as did a McConnell spokesman in a statement to Yahoo News.

“The Leader gave no such instructions,” wrote McConnell spokesman David Popp.

There is dispute over just how gridlocked the FEC has been. For many years, the three Republicans split with the two Democratic commissioners and one independent on the commission. Now, with two empty slots, there are only four commissioners and they often split along party lines, two to two.

Ravel found in a 2017 report that deadlocked cases had risen in 2016 to 37 percent, up from just 4 percent in 2006, and that financial penalties had dropped from $5.5 million in 2006 to just $595,425 in 2016. The Congressional Research Service found a 24 percent rate of gridlocked votes in 2014, up from 13 percent in 2008-2009.

Lee E. Goodman, a former Republican commissioner, said Ravel’s report relied on a “specious use of statistics,” but he did admit that the body is more gridlocked than in the past. “I would agree with the general trend that the percentage of 3-3 votes has overall increased slightly at the commission,” Goodman told Yahoo News.

Goodman said that the rise in deadlocked cases is the result of the Citizens United case, which left “gaps” in the law. “The Democrats wanted to fill every gap with the most restrictive and speech restrictive regulations they could throw at it,” he said. “It’s a fair debate about whether you want more regulation and less regulation.”

But McConnell made clear he wants to avoid disclosure of who is giving money, because to him, the ability to give anonymously prioritizes freedom of speech.

“Apparently the Democrats define ‘democracy’ as giving Washington a clearer view of whom to intimidate and leaving citizens more vulnerable to public harassment over private views,” McConnell wrote in his Post op-ed. “Under this bill, you’d keep your right to free association as long as your private associations were broadcast to everyone.”

In the battle over dark money, McConnell is going against a pro-disclosure view articulated by former Justice Antonin Scalia, who wrote forcefully in favor of transparency in political giving.

“Harsh criticism, short of unlawful action, is a price our people have traditionally been willing to pay for self-governance,” Scalia wrote in a 2010 opinion. “Requiring people to stand up in public for their political acts fosters civic courage, without which democracy is doomed.”

One of the debates around dark money is how much influence it actually has on politics.

Goodman argues it’s not as much as critics claim, saying the $150 million in money from undisclosed donors in the 2018 election was only a small percentage of all the money spent on political campaigns to influence last year’s contests, which he said totaled $5.72 billion.

A House Democratic aide countered that dark money plays an outsize role in competitive elections, since that the $5.72 billion figure includes spending by all campaigns, most of which are not competitive.

“Looking only at the aggregate percentage of dark money spending can be misleading and doesn't tell the whole story,” added William Gray, a spokesman for the reform group Issue One. “Dark money groups hold enormous sway over what issues are, and are not, debated in Congress and on the campaign trail.”

Issue One found that since 2010, dark money groups have poured $960 million into competitive races.

Goodman said that the reason some conservatives do not want to disclose their political giving is out of fear of retribution. “There is a perception that the left generally has become more aggressive in stigmatizing and vilifying and retaliating against conservative speakers,” Goodman said.

Issue One, which supports the reform effort, said the FEC is one of only a handful of agencies with an even number of commissioners.

“It should appall Congress and voters alike that the two agencies whose responsibilities include federal election oversight and security in our country — the FEC and [Election Assistance Commission] — are both the most dysfunctional and designed to be toothless tigers,” Gray wrote.

_____

Read more from Yahoo News: