‘That’s not who we are’: How a besieged heartland community rallied around its refugees

On a sunny and serene May evening, the city of Twin Falls, Idaho, gathered to dedicate a new flagpole.

It was the project of a local boy scout, whose troop was on hand to present the colors and lead the crowd of approximately 100 in the Pledge of Allegiance. Refreshments were served and the national anthem was sung, a brief ceremony that featured prayers and thank-yous to those who had donated time or money to the project.

Seated among the crowd of native-born Idahoans was a family from Sudan that had immigrated to the United States only a few days earlier from a refugee camp in Chad. Sitting next to them was a family who had fled the Democratic Republic of Congo. The flagpole had been installed outside the College of Southern Idaho Refugee Center, a ceremony that was the second act in as many days from a community that sought to affirm its position on refugees after months of headlines that resulted in, as the mayor put it in a recent speech, “a community painted with a brush by artists who are not in Twin Falls.”

The night before the flagpole was christened, citizens gathered into the crammed city council chamber, where weeks of debate and public input came to a close with a 5-2 vote: Twin Falls would be known as a “neighborly city.” It was a resolution that changed no policy but felt necessary to show the world — as one council member put it — “that’s not who we are.”

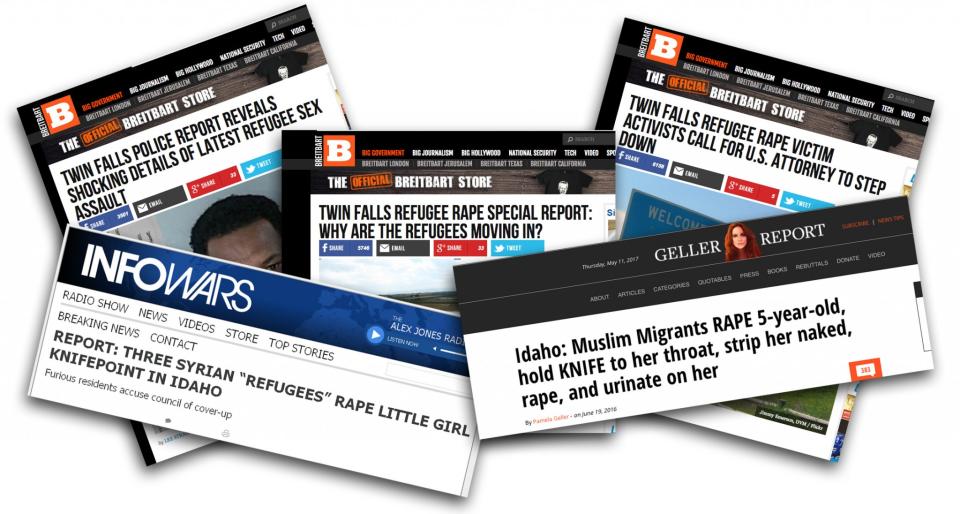

The actions were in response to more than a year of controversy and negative stories in right-wing media and assorted comments sections, a trying time for a city that’s accepted refugees for decades but found its image sullied and citizens threatened. It’s an example of how the worst elements on the Internet can bleed into everyday life, and a cautionary tale of how the charged politics of immigration can play out in a community that believed it was doing the right thing by welcoming families displaced by conflicts in distant countries. After three Muslim refugees — all children — were charged in a sexual assault on a 5-year-old girl, right-wing media conjured up a lurid crime wave among the Muslim immigrants in the community. Breitbart embedded a reporter in Twin Falls to look for stories that “[don’t] fit the narrative about the benefits of diversity that the media and politicians try to spin.”

Twin Falls weathered sensationalized charges, grotesque threats and a militia group’s anti-immigrant demonstration. And the community has become the venue for a defamation lawsuit by yogurt maker Chobani, one of the area’s largest employers, against conspiracy monger Alex Jones, for stories with headlines such as “Idaho Yogurt Maker Caught Importing Migrant Rapists.”

After a long two years, Twin Falls residents didn’t recognize the city that was being portrayed in the media — so they decided to do something about it.

~

Twin Falls is the hub of the Magic Valley, sitting two hours southeast of Boise. It was founded in 1904 by I.B. Perrine, a local rancher who helped spearhead the irrigation system that made farming possible across the region. Its population is more than 90 percent white, with a large Mormon contingent, and until the recent spate of attention the area was probably most famous for stunt motorcyclist Evel Knievel’s aborted plan to jump over the Snake River Canyon in 1974. The myriad reports about parts of Middle America crumbling do not apply to Twin Falls. The town is booming, with a population creeping toward 50,000 and 3 percent unemployment, its economy buoyed by the local dairy industry and massive new factories at Chobani and Clif Bar. When you roll into town from the north — crossing the same river that Knievel had hoped to jump — you immediately travel through an expanse of shopping plazas with nearly every conceivable store and restaurant. As you approach downtown, you can’t avoid the construction, as entire streets are shut down for revitalization projects.

The city is one of two in Idaho — the other being Boise — to accept refugees for resettlement, a tradition that began in the early 1980s with immigrants from Southeast Asia. Eastern Europeans began making their way from the former Soviet bloc a few years later, and the 1990s saw a surge from those escaping the Bosnian civil war. Over the years, the community began to resettle those from camps in Africa and the Middle East, averaging around 300 migrants per year. The refugees were for the most part professionally successful, with adults taking jobs in local businesses like dairy farms and children fitting in with the school district, which had adapted to the stream of multilingual new students by opening a newcomer center. Jobs were plentiful, the cost of living was low and it was an ideal place for displaced immigrants to settle.

In 2015 things started to shift. There were heightened tensions from the presidential election and from the announcement from the refugee center that there would likely be Syrians in the next wave of migrants. The fear that terrorists would infiltrate the refugee process were raised nationwide, and Twin Falls was not excluded from those concerns. There were calls from a representative in the Idaho state legislature for a special session on refugees, protests from a militia group and attacks on minorities in the community: An Islamic center in town was vandalized, with “Hunt Camp” spray-painted outside of it, a reference to a nearby area that was used to intern Japanese-Americans during World War II.

What had been a local story went national in June 2016, when the headline “Idaho: Muslim Migrants RAPE 5-year-old, hold KNIFE to her throat, strip her naked, rape, and urinate on her” appeared on the website of Pamela Geller. Geller is described by the extremist-group monitor Southern Poverty Law Center as the “anti-Muslim movement’s most visible and flamboyant figurehead,” and her pushing of the story immediately spread it to right-wing and antirefugee outlets. On the conspiracy site Infowars, the headline initially read “Report: Three Syrian ‘refugees’ rape little girl at knifepoint in Idaho” with the subhead “Furious residents accuse council of coverup.” Breitbart embedded a reporter in the city, producing a series of stories on the case and painting the area as a crime-infested wasteland.

The problem with the coverage was that there was no rape, no knife, no Syrians and no coverup. There was a horrific incident: On June 2, three refugees from Eritrea and Iraq, ages 7, 10 and 14, sexually assaulted a 5-year-old girl at a Twin Falls apartment complex. The boys eventually pleaded guilty to multiple charges and the records were sealed because those involved were minors. Some members of the community said the case was mishandled, but Twin Falls Police Chief Craig Kingsbury told the Times-News last month that “I’ve always felt that we followed proper protocol and procedure.” Both Kingsbury and the prosecutor, Grant Loebs, spoke publicly during the process.

Refugees that resettle in Twin Falls go through the vigorous federal vetting process that has nearly two dozen total steps, with Syrians undergoing additional screening. The narrative pushed by some outlets that the refugees’ presence was causing a crime wave was rebutted by Kingsbury, who told Yahoo News it was inaccurate to say the refugee community was causing his force problems. Recent studies have shown that a higher refugee population often correlates with lower crime rates.

An improbable flashpoint in the controversy was the Chobani plant — the largest in the world, the company claims — which opened in 2012 and now has about 1,000 workers. The company’s founder and CEO, Hamdi Ulukaya, an immigrant from Turkey of Kurdish descent, has found himself a consistent target of right-wing attacks, in part because of his company’s policy of hiring immigrants — in the words of Breitbart, a scheme “to replace American job-seekers with cheap, compliant labor.”

Alex Jones found the Chobani angle irresistible as well, and his website Infowars began to promote the story with headlines like “MSM [mainstream media] Covers for Globalist’s Refugee Import Program After Child Rape Case” and “Idaho Yogurt Maker Caught Importing Migrant Rapists,” while accusing the company of bringing crime and disease to Twin Falls.

Chobani responded by suing Jones and Infowars for defamation. Jones claims to have the ear of President Trump and interviewed him as a candidate in December 2015, where Trump told Jones his reputation was “amazing” and that he would not let him down.

“I’m choosing this as a battle,” said Jones last month in response to the suit. “On this I will stand, I will win, or I will die.”

“I’m going to be going to Idaho,” added Jones. “I’m going to go on that local radio station. I’m going to bring investigative crews there. I am going to show what the locals are doing. I am going to show the Islamicists getting off of the planes. You want a fight? You better believe, baby, you’ve got one.”

Infowars did not respond to inquiries about when Jones would be traveling to Idaho.

The publicity quickly embroiled the community in a controversy for which it was unprepared. Mayor Shawn Barigar, his wife, city council members and College of Southern Idaho staff members received a slew of angry emails and voicemails, some containing threats so violent they were forwarded to the police and FBI for investigation.

“Have you any idea how many Americans are hoping and wishing your daughter, wife, mother, sister, aunt, or niece gets gang raped by those [expletive] piece of [expletive] sand [expletive] you’re so [expletive] enamoured [sic] with?” wrote the anonymous sender of one email, according to the Times-News. The message was one of those forwarded to the FBI because of another, even more threatening comment in it.

Barigar told Yahoo News things never reached the level it did surrounding the “Pizzagate” conspiracy — in which an armed man fired shots in a Washington, D.C., restaurant as he investigated claims that it was a front for a pedophile ring — but there were plenty from outside the community voicing their thoughts at the weekly council meetings. Many of the threats also came from outsiders.

But as the town suffered through the onslaught of headlines and fear-mongering, there was a bright spot: Donations to the refugee center surged, according to its executive director Zeze Rwasama, and so far they haven’t slowed down. Rwasama understands the hardships suffered by those he’s helping to resettle. He grew up in Congo but fled to Rwanda in the mid-1990s to avoid death squads in his home country. He lived in a United Nations refugee camp there for six years before immigrating to Salt Lake City in 2001, eventually moving to Twin Falls to begin work at the refugee center in July of 2014. The center now has a storage area full of supplies, along with volunteers who have come forward to help with everything from mentoring new arrivals to assisting with one-on-one English language lessons.

In addition to their time and money, the people of Twin Falls also demonstrated their strong support of the refugees. Multiple Twin Falls residents used the term “silent majority” when discussing the program, stating that many in the community had thought quietly helping out the migrants was enough, but realized that with all the negative attention they needed to speak out. The city council’s consideration of the “neighborly city” resolution provided them an opportunity.

“I think that as we have gone through this discussion [about refugees] over the course of the last year,” said Mayor Barigar in an interview with Yahoo News last week, “there’s probably been disproportionate attention paid to the opponents of refugee resettlement — sort of the squeaky wheel syndrome, where they tended to be the ones who were showing up to council meetings. But over the course of the last few months — and especially the last month, with this request from the Boy Scouts specific to a resolution — we’ve certainly seen more local supporters of not only the refugee center itself but refugees and the resettling program.”

Barigar was referring to an April proposal from two scouts to make Twin Falls a “welcoming city,” following the actions of Boise and Ketchum, a city 80 miles north. The measure evolved into classifying Twin Falls as a “neighborly city,” a minor semantic departure from the welcoming resolution that didn’t contain the word “immigrant” or “refugee” but emphasized parts of a 2012 strategic plan that urged citizens, businesses and organizations “to build a community where all residents are welcomed, accepted and given the opportunity to connect with each other without bias in pursuit of common goals.” There was concern expressed by some citizens that the measure might prove a stepping stone to status as a sanctuary city, one that shields undocumented immigrants from deportation. But council member Greg Lanting, who adamantly supported the measure as necessary to counter some portrayals of the town in the media, was just as vocal about how he would never vote to make Twin Falls a sanctuary city.

More than 75 percent of those who spoke at the public hearings supported the resolution, with many residents telling their own families’ immigrant histories or about the humbling experience of working with refugees who came to the United States with nothing. But Vice Mayor Suzanne Hawkins — one of the two no votes — said during the hearing Monday night that 80 percent of the feedback she had received was against the resolution, with citizens fearful of coming forward and being targeted by supporters. Hawkins declined to elaborate when asked by Yahoo News about specifics of those concerns, but those who voiced opposition during the hearings did so for a variety of reasons. There were the concerns about taking a step toward sanctuary city status and a belief the council’s time could be better spent but also more conspiratorial worries, such as accusing the Boy Scouts of a liberal agenda and warning of a broader “treason by contract” being committed by businesses in the area.

The council chose not to take any more public input on the night of the vote, but roughly two dozen residents had signed up to discuss the resolution, most of whom planned to speak in support of the measure. When the vote went final, there was loud applause in the room before much of the crowd filed out into the spring evening, smiling and shaking hands outside.

While the resolution was largely ceremonial, those in the refugee community still appreciated it.

A Muslim refugee named Ado, 29, immigrated to Twin Falls with his mother and sister after his father was executed in a prison camp during the Bosnian civil war. They arrived on September 9, 2001, and in the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks he dealt with bullying and racism that was so intense he faked illnesses in order to avoid school until his English improved. Ado is now married to a fellow Bosnian immigrant, and the couple has a 6-month-old daughter.

“It’s like a weight lifted off your shoulders,” said Ado of the resolution. “It was a great feeling knowing there’s people here that support us and they wanted to make it a welcoming city, but I was also nervous because there’s a lot of tension out there. I didn’t want something to happen — something stupid — that escalates into a huge blow-up.”

Ado’s mosque was one of those vandalized over the past two years, and while he said he enjoyed growing up in Twin Falls, he’s still careful about discussing his faith.

Rwasama was also pleased with the resolution passing.

“With the negative coverage,” said Rwasama, “people might think Twin Falls doesn’t welcome diversity. This resolution shows that simply isn’t true. This is a great place to settle and a great place to succeed.”

Bill Colley, a local conservative radio host, spent his show the morning after the vote mocking the resolution as “[smacking] of political correctness” and taking calls from angry community members. But even Colley had admitted concern about some of the fringe elements in the area, writing in April that it was time for Republicans to “disown” the extremists in Twin Falls.

The process of funding Twin Fall’s newest flagpole engendered further positive response, according to the scout who spearheaded the fundraising. Porter Buckley, 13, told Yahoo News that he wanted to help the refugee center in some way and settled on the pole installation after it was suggested by officials there.

“Lots of people thought it was a great idea,” said Buckley, when asked about the reception he got while soliciting donations.

One sign of community sentiment came last year when Rick Martin, a conservative activist and opponent of the resettlement program who lives outside the city, began collecting signatures for a county ballot measure on banning refugee centers in Twin Falls County. He needed 3,843 signatures from the population of approximately 80,000 to gain access to the ballot. He managed to collect just 894, falling well short of the necessary total.

After a tumultuous two years, the biggest threat to the refugee program in Twin Falls now is likely the White House. The immigration executive orders issued earlier this year — both blocked by judges — sought to cut the total number of annual refugees accepted from 110,000 to 50,000. Jan Reeves, director of the Idaho Office of Refugees based in Boise, told Yahoo News that there is uncertainty among resettlement organizations about the future, as the number of refugees being halved would also result in funding cuts and a likely reduction in services. One office in Boise is already set to close, part of a national organization shuttering half a dozen offices across the country.

“The executive order implementation didn’t come with instructions so people would know exactly what to do,” said Rwasama. “Seems like decision makers didn’t think about that when all of a sudden they want us to reduce our budgets by half. I would say that many agencies did incredible jobs to try and keep their doors open planning for next year.”

As resettlement organizations and the displaced people they aim to help await clarity on their fate, Twin Falls is setting an example of the determination of ordinary Americans to protect refugees from Islamophobes, from conspiracy theorists, from right-wing media — and from a president who came to power riding all three.