Texas history museum dissects treaty that ended Mexican American War and changed the world

Be honest: What do you really know about the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo?

The accord that formally ended the Mexican-American War (1846-1848) radically altered the destinies of both countries. So crushing was the defeat of Mexico that the United States demanded and received Texas, California, Nevada and Utah as well as big slices of Arizona, Colorado, Wyoming and New Mexico.

Imagine the U.S. without all that territory. Imagine Mexico with it.

And yet how did the 1848 treaty come about? What does it actually say? And how did it affect those living on both sides of the new border, including Native Americans and African Americans, whose destinies were decided without their consent?

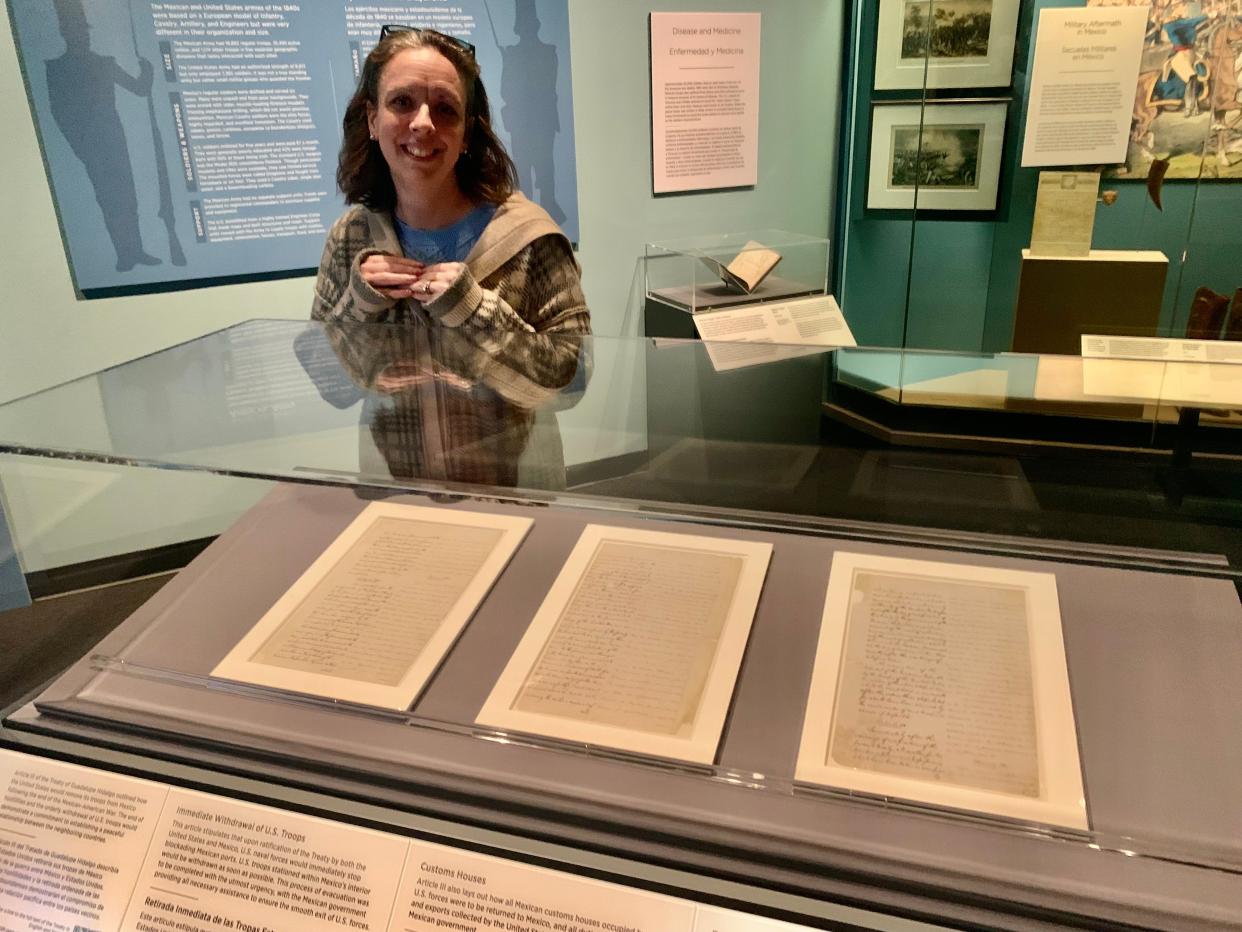

A new pop-up exhibit at the Bob Bullock Texas State History Museum helps clear the air. Located on the second floor, it includes pages — originals and copies — of the treaty, which are on loan from the National Archives.

How a pop-up show fits into the long-term museum plan

"Legacies of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo" represents a relatively new type of show for the Bullock, which opened as the premier museum on the subject of Texas history in 2001. As the Bullock slowly updates and upgrades its permanent exhibit — the modernized rooms on the ground floor dedicated to early Texas were unveiled in 2018 — the more recent curatorial work upstairs has been completed incrementally.

As senior curator Kathryn Siefker explains, revisions on the second floor are moving forward one room at a time. The treaty popup show, which lasts through Feb. 16, 2025, allows Siefker the opportunity to rethink what will permanently fill that gallery — which typically covers the Texas statehood period.

"We had been talking about the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo for a long time," Siefker says. "And we've been working with the National Archives to borrow some actual pages from the treaty."

A reminder: By design, the Bullock does not own any of the artifacts it displays. Even the elaborate exhibit on the shipwrecked La Belle, which transported the doomed colony of René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, does not belong to the state museum, but rather to the French government.

Everywhere you look, it's all on loan.

Like the refreshed historical exhibits downstairs, the "Guadalupe Hidalgo" pop-up feels more like part of a grown-up museum than an amusement park. Sure, one can be entertained by the uniforms, weapons, maps and so forth, but the goal is to help visitors understand the history better.

To that point, all the texts are translated into Spanish, part of a recently completed museum-wide project to make history more accessible to a wider swath of the state's residents and tourists.

What will I see at the Bullock?

In a blue-tinted room under low general lighting, the sharply defined individual displays of "Legacies of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo" examine the times before, during and, especially, after the world-changing agreement.

They cover the basic contours of the Mexican-American War, which started in 1846 after 30 years of regional chaos. The U.S. insisted that Mexico's border with the recently annexed Texas ran along the Rio Grande, which the Republic of Texas had claimed, rather than the more northerly Nueces River, which Mexico recognized.

President James K. Polk dispatched Gen. Zachary Taylor to the Texas coast to secure the land between the rivers, the "Nueces Strip." Supplies and troops were funneled through Lavaca and Corpus Christi. In fact, a hilltop cemetery in the latter city, Old Bayview, laid out in 1845, is the oldest federal military graveyard in the state.

To Mexico, the military move into the strip represented a clear provocation.

The Battle of Palo Alto, just north of the Rio Grande, previewed later ones in Mexico's interior. The U.S. army generally dominated its opponents. Among the combatants, then-Lt. Ulysses S. Grant observed the stark brutality visited on Mexican civilians by the Texas Rangers, who joined the federal forces. Meanwhile, halfway across the continent, American explorer John Frémont was fomenting rebellion in California against Mexican rule.

After U.S. forces occupied Mexico City, the nation, already weakened by decades of infighting, was doomed. As peace negotiations began, many in Mexico resisted the loss of any of its sovereign territory. Yet the U.S. took half of it. The U.S. agreed to pay for Mexican damages in the war, among other concessions.

Pages of the treaty borrowed from National Archives — both early, "dirty" and later, "clean" copies, to demonstrate which articles were eventually left out — will be rotated during the run of the show. Currently on display is an excerpt stipulating that the U.S. end its blockade of Mexican ports and withdraw its troops from Mexico, especially from Mexico City.

The treaty's unintended consequences

The treaty was signed in a town outside Mexico City called Guadalupe Hidalgo on Feb. 2, 1848. It was ratified by the U.S. Senate on March 10, 1848, and approved by Mexico's Congress on May 30, 1848.

For any history buff concluding that the story ended there, a good deal of the context and detail of the treaty's legacy would be missed.

As the exhibit explains, for instance, some 44,000 soldiers on both sides died. It is somewhat surprising to learn that 88 percent of the American war deaths were due to infectious diseases. "The U.S. assault on Veracruz was initially planned to avoid the 'sickly season' when yellow fever and other diseases were known to be surging," one wall text reads. "When the peace treaty was written in 1848, Article IV included instructions on troop movements to avoid the sickly season to prevent more deaths as the soldiers returned home."

The exhibit demonstrates how the treaty included protections for Mexicans who would soon become Americans. And indeed, many of these former Mexican families thrived and even intermarried with European and American newcomers after the war. Later, however, land speculators and violent militias swooped in to deny these Mexican Americans their birthrights. (The book to read is "Stolen Heritage: A Mexican-American's Rediscovery of His Family's Lost Land Grant" by Abel Rubio.)

As for Mexico, the war showed how much a long period of political instability had fatally weakened the country. Although more turmoil followed the war, a generation of liberals united the country in the 1850s, and it was able to fight off the French during its Second Intervention during the 1860s. To some historians, this act of nationalist self-defense laid the foundation for modern Mexico.

For the U.S., the war proved the need for a permanent standing army. The military grew expansively after the war, especially once it began fighting Native Americans in the newly acquired territories. Officers who were West Point graduates and had seen action in Mexico and in the American West led both sides during the Civil War.

The treaty accelerated internal tensions in the U.S. As early as 1836, Americans had debated admitting Texas to the Union as a slave state. "They were concerned Texas would upset the Congressional balance of power between the states," reads one wall text, "and that its sheer size would spread slavery into the West." Soon after the treaty was signed, the Compromise of 1850 admitted California as a free state and reduced the size of Texas, a slave state.

The treaty, however, strengthened the Fugitive Slave Act, which required even free states to return enslaved fugitives and threatened with imprisonment anyone who helped them flee. This intensified the clash between abolitionists and backers of slavery, which contributed to the start of the Civil War not long afterward in 1861.

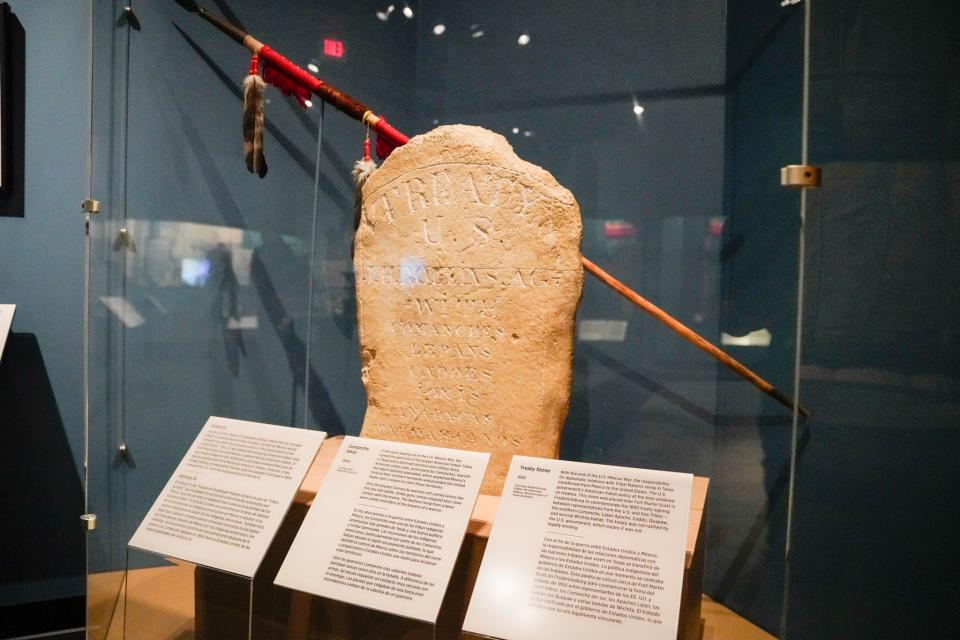

Perhaps the most eye-opening details of this exhibit deal with how the treaty affected sovereign Tribal Nations that had established diplomatic agreements with Spain and then later Mexico, Texas and the U.S. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo undermined all those accords. The new borders divided some nations and separated some tribes from vital resources.

The Mexican-American War and the subsequent Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo barely pierce the consciousness of most Texans today.

Yet the war and treaty "remain a profound scar for many," one wall text reads. "Mexico was left with the profound grief of losing over half its land to its neighbor and the shame of having been occupied by a foreign army. In the U.S., the acquisition of the Southwest changed the nationality of approximately 150,000 Mexicans overnight. Lands that had been their home for centuries were suddenly foreign.

"The losses to Mexico eventually created a nationalism that brought stability to the nation. In the U.S., a whole new culture came into being, that of the Mexican American, whose powerful identity has contributed to the richness of America."

'Legacies of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo'

When: 10 a.m. to 5 p.m daily through Feb. 16, 2025

Where: Bob Bullock Texas State History Museum, 1800 Congress Ave.

Parking: Given the recently reconfigured Capitol Mall, the best parking is found below the museum. The entrance to that garage is on West 18th Street.

Tickets: $9-$13 for the museum, excluding the IMAX theater

Info: thestoryoftexas.com

Michael Barnes writes about the people, places, culture and history of Austin and Texas. He can be reached at mbarnes@gannett.com. Sign up for the free weekly digital newsletter, Think, Texas, at statesman.com/newsletters, or at the newsletter page of your local USA Today Network paper.

This article originally appeared on Austin American-Statesman: 'Legacies of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo' expands Texas history