Texas blocks oil and gas wastewater wells amid earthquakes. What is New Mexico doing?

Earthquakes continued to rumble the Permian Basin in West Texas and southeast New Mexico in late 2023, leading regulators on both sides of the state line to act.

The Texas Railroad Commission announced in December 2023 that it was suspending permits for oil and gas wastewater disposal in Culberson and Reeves counties along the border of the two states, as the fluid injection was believed to be the cause of the quakes.

New Mexico’s Oil Conservation Division reported its phased approach at lower disposal injection near earthquake sites appeared to be working, but the agency was looking ahead at new and more stable places and methods of disposal.

More: Can smaller tremors protect New Mexico from oil and gas earthquakes in Permian Basin?

Oilfield wastewater, known as produced water by the industry, is brought to the surface during drilling for crude oil and natural gas, sometimes up to 10 barrels per barrel of oil.

Traditionally, this fluid, high in brine and toxic chemicals, was pumped back underground for disposal into the formations it came from, and recently some oil and gas companies began treating it for use in subsequent drilling operations.

But a lot of the water is still disposed of via injection wells, and the connection between the wells and earthquakes throughout the Permian applied pressure to regulators to limit the practice in areas of increased seismic activity.

More: Here's what to know about New Mexico's latest efforts to reuse oil and gas wastewater

Dylan Fuge, director of New Mexico’s Oil Conservation Division said the agency was shifting from a reactive approach to prevention, potentially blocking new injection well permits in areas known to see heightened seismicity.

In November 2021, the OCD enacted rules to cut injection volumes at wells based on their proximity to seismic events and the magnitude of such events.

He said this appeared to be reducing the number of events in New Mexico and the basin, but more action could be needed to potentially find alternative means to dispose of the water that might not lead to the quakes.

More: Shaky Ground: The link between the Permian Basin's fossil fuel industry and earthquakes

“We have been successful in doing the hard stop and getting things to calm down. I think the next phase for us going forward is how to manage these areas. We need to address the need that is out there,” Fuge said. “I don’t think the work is done. We’re going to need to continue making progress.”

That need could grow in the coming years as oil and gas production was expected to increase in the Permian for the foreseeable future, Fuge said, meaning regulators will continue watching induced seismicity.

He said a typical well in the Permian today generates about three to four barrels of wastewater per barrel of oil, and that while the OCD has sought to encourage more treatment and reuse of the byproduct, disposal injection was likely to continue.

More: Fault lines at Texas-New Mexico border complicate earthquakes linked to waste water disposal

“I think it’s going to be an ongoing issue that we’re going to need to pay attention to. I think there is a hope that we’ll be able to control it. It’s going to require vigilance and focus,” Fuge said. “With growing production, you do have significant volumes of produced water that needs to be properly disposed of.”

Is New Mexico’s approach stopping the quakes?

The OCD has been able to allow for some minor increases in disposal volumes in wells within its County Line Seismic Response Area in Eddy and Lea counties, Fuge said, and the agency is taking a hard look at applications for new injection wells in the area.

“In most circumstances, we’re of the opinion those applications cannot proceed,” Fuge said. “It’s unclear how they have a viable path forward without upsetting the balance in those areas. Contemplating those is potentially problematic.”

More: Oil and gas is 'deforming' New Mexico's land, study says, as drilling set to grow

And the division was recently approved by the Oil Conservation Commission for a pilot project to study shallow injections as an alternative to the deep injection that was shown to cause seismicity in the response area.

“We’re also exploring other disposal options,” Fuge said. “That’s another step we’re taking for water management, looking at other formations for disposal opportunities.”

For the Railroad Commission stopping the shakes meant suspending injection well permits in the agency’s Northern Culberson-Reeves County Response Area, according to an order issued Dec. 19.

More: Industry, regulator cooperation dampened Oklahoma's quaking issues over time

That would affect 23 wells in the area along the state’s border with southeast New Mexico, the order read, beginning Jan. 12.

The Texas Railroad Commission cited seven earthquakes in the area between Nov. 8 and Dec. 17, 2023 ranging in magnitude from 3.6 to 5.2 – a quake reported Nov. 8 near Coalson Draw, Texas that was reportedly felt as far west as El Paso and as far north as Albuquerque.

That was followed by several quakes of smaller magnitude in the hours and weeks after, according to data from U.S. Geological Survey (USGS).

More: Only half of New Mexico's oil and gas operators are following state air pollution rules

“These are the most recent events in a continuing sequence of earthquakes that have occurred in this area over the last three years,” read the order which also cited several specific formations beneath the sought-after Wolf Camp oil and gas deposit.

The USGS reported 569 quakes of an M 2.5 or greater throughout the Permian Basin in both states, and in both the western Delaware and eastern Midland sub-basins.

While most were in Texas, several quakes reported were just over the border in New Mexico.

More: Oil and gas companies seek solutions to wastewater, drought in New Mexico, Permian Basin

That included Eddy County, led by an M 3.4 event about 1.5 miles west of Carlsbad on April 18, and another M 3.2 north of the city on June 6.

A string of quakes was reported near Malaga along the state line, including an M 3.4 on March 26, and an M 3.3 on Jan. 15, and several events between M 2 and M 3.

In Lea County, the USGS reported an M 3.5 on Sept. 22 and an M 3.1 July 25 near Eunice.

More: Southeast New Mexico shook by early morning earthquake reported in West Texas oilfield

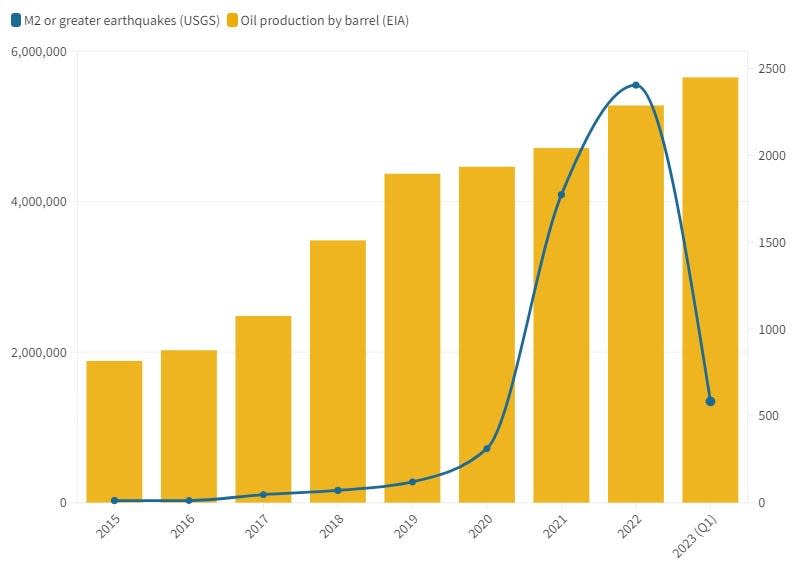

Tremblors appeared tied to increased oil production, research says

The increasingly frequent and higher magnitude of the quakes were tied to the oil industry and its water disposal through a growing body of research.

Seismicity caused by the injection wells began in the region in 2016, according to a December 2023 study conducted by scientists at the University of Texas – Austin and University of Pennsylvania and published in the journal Earth and Planetary Science Letters.

That was at the tail end of a boom in oil production in the basin led by the expanded use of fracking and directional drilling in the region, which was followed by subsequent drilling spikes in 2019 and 2022 following the COVID-19 pandemic and Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Editorial: Is New Mexico ready for increasing earthquakes? That's what our reporting is tackling

The seismicity, known to grow during times of heavy production, is caused when injected fluid travels underground into ancient faults, adding pressure and causing them to slip, the study read.

The slipping fault causes vibrations that can reach the surface and are felt by people as earthquakes.

This is what was behind the increase in quakes in the Delaware Basin, the study concluded.

More: Did you feel that? New Mexicans can report feeling an earthquake to help track data.

“Subsurface disposal of wastewater and hydraulic fracturing from oil-gas operations are the two primary causes of induced seismicity in this region, with the bulk of the seismicity being attributed to wastewater disposal,” read the study.

The resulting seismic movement increased “significantly” starting in 2017 to a peak in 2019 and then declined back to 2017 levels, the study read, as fracking rates decreased.

As oil and gas production was expected to continue its growth in the Permian, Fuge said New Mexico and Texas must remain prepared for the potential of increased seismicity.

He said although more earthquakes are reported there, the problem was not confined to Texas.

“The industry in the Permian basin is interconnected. Water volumes do travel across the border. Any decisions by either state to restrict or curtail disposal volumes have effects on different jurisdictions,” Fuge said. “The Permian Basin is a shared play, and we have operators with operations in both.”

Adrian Hedden can be reached at 575-628-5516, achedden@currentargus.com or @AdrianHedden on the social media platform X.

This article originally appeared on Carlsbad Current-Argus: Earthquakes from fracking, water disposal prompt action in New Mexico