A new test for autism hopes to help doctors diagnose before symptoms show

Researchers have developed a first-of-its-kind test for autism that they say can find markers of risk in a single strand of hair, an innovation that might help clinicians identify it in young children before they miss developmental milestones.

The test — which is still in the early stages of development by the startup LinusBio and a ways from federal approval — is a diagnostic aid, meant to assist clinicians in identifying autism but not to be relied on alone. Because hair catalogs a history of exposures to metals and other substances, the technology uses an algorithm to analyze it for patterns of particular metals the researchers say are associated with autism.

This test is the first to analyze this type of exposure history over time. The analysis predicted autism accurately about 81% of the time, according to a peer-reviewed study published last month in the Journal of Clinical Medicine.

The researchers hope the technology could help children receive early intervention treatments sooner and also lead to the development of new drugs or therapy models for young children.

“The technology is incredibly novel. The use of hair and the type of measurements they’re doing with hair is innovative,” said Dr. Andrea Baccarelli, a professor of environmental health sciences at Columbia University, who was not involved in the company’s research. “It’s groundbreaking.”

The causes of autism remain mysterious, and LinusBio is entering an ongoing and heated debate over what roles a tangle of environmental and genetic factors may play. Researchers have discovered myriad risk factors associated with autism, including infections during pregnancy, air pollution and maternal stress. Some pollution from metals, which is known to cause neurodevelopmental problems, has been associated with it too.

“Those risk factors all function on a background of genetic risk,” said Heather Volk, an associate professor in the department of mental health at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. She added that in the past 15 years, more researchers have turned their attention to environmental factors.

NBC News spoke to six independent experts from different scientific backgrounds about LinusBio’s test. Although many were excited about the potential of the underlying science, most said caution is warranted and that more research is needed. All agreed the findings should be replicated by other teams.

“There is certainly much more work to be done before concluding that this test is a valid measure of autism spectrum disorder risk,” Dr. Scott Myers, a neurodevelopmental pediatrician at the Geisinger Autism & Developmental Medicine Institute, wrote in an email.

How the test works

The LinusBio test analyzes the history of the metabolism, telling the story of what substances or toxins the child has been exposed to over time, according to Manish Arora, the company’s co-founder and CEO, who is also a professor of environmental medicine and public health at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, the academic arm of the Mount Sinai Health System. The technology was developed from research completed at Mount Sinai.

For an infant, hair can provide a glimpse of the exposures in moments critical to development, like the third trimester of pregnancy.

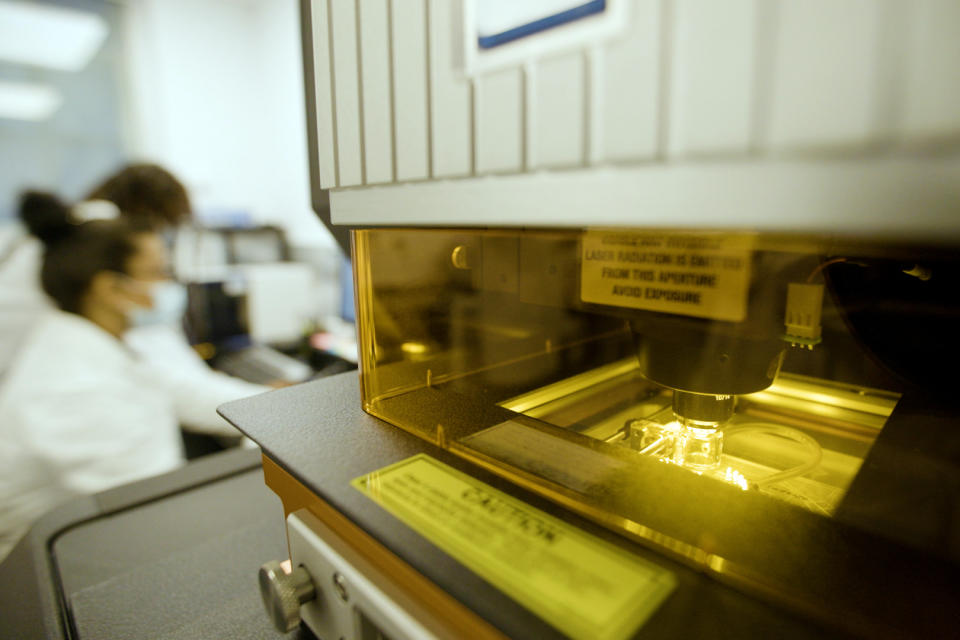

The test runs a laser along the length of a hair, using its energy to turn it into a plasma for analysis. A centimeter — less than half an inch — of hair captures roughly a month’s worth of exposure data, Arora said.

As a tree’s rings tell scientists about growing conditions each year, hair growth allows researchers to understand what was happening in someone’s body during specific moments in time. LinusBio says its test can reveal metal metabolism in 4-6 hour increments.

“It’s almost like having a security camera where you can go back and get a look at four pictures a day,” Baccarelli said.

The technique creates huge amounts of data. That’s where a machine-learning algorithm takes over — it’s trained to look for patterns of dysregulation in metals that the researchers believe are biomarkers of autism.

“We can detect the clear rhythm of autism with just about one centimeter of hair,” Arora said.

Autism diagnosis timing

Arora and his team hope their technology could help young children, even newborns, receive early interventions for autism sooner than they can now.

“The problem with autism is it’s diagnosed at the age of 4 on average. By that time, so much brain development has already happened,” he said. “We want to enable early intervention.”

There is not yet a biological test for autism spectrum disorder. Rather, children are often diagnosed after parents notice behavioral differences, such as avoiding eye contact, delays in language or not pointing. But these behaviors vary widely, and autism can also occur alongside other conditions such as Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), anxiety and mood disorders.

Specialists use neurological examinations, language assessments, behavior observations and other methods to diagnose a child. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends autism screenings at 18 months and 24 months.

Early intervention for autism typically involves individualized instruction with a trusted teacher, according to Annette Estes, director of the University of Washington Autism Center in Seattle. These programs are implemented when symptoms emerge to address specific developmental needs, and often look like play.

“Babies are little scientists. They’re trying things out and looking for feedback,” she said. “You can really accelerate development in all kids.”

But little is known about what effect pre-symptomatic intervention might have for young kids at higher risk of autism.

“We have theories about what we might do,” Estes said, ”but it hasn’t been studied extensively.”

Next steps, more data

The Food and Drug Administration gave LinusBio’s test a “breakthrough” designation, which is intended to speed up the regulatory approval process for new technology when there aren’t alternatives on the market. The designation does not change approval standards, and the company faces regulatory hurdles before its device could be considered for widespread use in the U.S.

In the published study, the researchers trained and tested their technology by evaluating hair samples from 486 children across three countries: Japan, Sweden and the United States.

In an analysis of 97 hair samples, the algorithm correctly identified cases in which autism spectrum disorder was diagnosed more than 96% of the time. It identified negative cases correctly about 75% of the time. The group tested included 28 cases of autism, a much higher proportion than in a general population.

“This needs to be repeated on bigger sample sizes and a bigger data set,” Volk said.

The company, which has raised more than $16 million in venture capital investment, is working on an expanded study and has collected samples and data in a group of about 2,000 people.

Because the predictive value of a test depends on how prevalent a condition is in the group being evaluated, the test’s accuracy would be diminished in a general population, where autism rates are around 2%.

That’s part of the reason the LinusBio team sees the tool as merely an aid to clinicians in reaching a diagnosis.

“No clinician should make a decision on if a child has autism solely based on this,” Arora said. “This provides a crucial piece of information, but not the only piece of information.”

The test could be most useful in groups with a higher risk of autism, such as children who have missed developmental markers or have siblings with autism.

Researchers also think accuracy could improve with repeat testing — analyzing and comparing multiple strands of a child’s hair.

However, from Estes’ perspective, no test or technology can address the biggest and most important barrier for families of children seeking care for autism: Finding trained clinicians who can make a specialized diagnosis and building a care team for the child. Many parents can’t get help even if they do notice developmental delays, she said.

“On-time intervention is something most kids don’t have access to at the moment,” Estes said. “We know how to help kids. It’s really hard to get access.”

Arora hopes that in the future, the new technology could also yield clues about what is changing in a child’s body as autism manifests. Perhaps eventually, that information could open up new pathways for the development of drugs or therapies for autism, he said.

LinusBio said it also plans to apply the approach to other health conditions with known links to environmental factors, including Lou Gehrig’s disease or ALS, gastric disorders and certain cancers.

This article was originally published on NBCNews.com