How terror in a jungle became a life's mission for Joel Jimenez

Alpha 33, the big M48 Patton tank, rumbles out of Camp Red Devil and lumbers into the valley of the Kwan Tri Province. It’s the farthest north American stronghold.

The mission is to flush out the enemy.

Three men are inside. Pancho rides outside on the back. He’s the loader. He loads the ammo into the 90mm cannon and the 50-caliber machinegun.

It’s mid-afternoon when Pancho hears the high-pitched whine. The rocket hits the Patton with an enormous explosion. For a moment, Pancho feels himself floating. Then he sees muzzle blasts in the trees.

They’re coming – maybe 35, maybe 40 of them. North Vietnamese forces.

He fights off sheer terror, swings the 50-caliber into action, shooting at anything that moves. He sees the tracers strike the trees.

Sometimes he hears Thump! Thump! Thump! The sound of bullets hitting bodies.

He fires hard and fast as they swarm in. So hard and fast the barrel burns up. Useless.

He sees an M16 rifle close by and grabs it. He fires and yells.

Fires and yells.

Empties one clip, finds another. Empties it. And another.

Then no more bullets.

He’s the loader. He knows there are grenades in the ammo bin.

He grabs them two at a time.

Pulls the pins. Throws them.

From inside the tank: Pancho! Hey, Pancho! They’re climbing up! They’re climbing up!

The enemy is on him.

He throws the grenades straight down at the sides. He might blow himself up with the enemy.

When the grenades are gone, there’s just a bayonet.

The bullets hit him.

Thump! Thump! Thump!

Neck, back, chest.

Consciousness fades, but in the distance, an unmistakable sound.

Rat-tat-tat-tat-tat!

The big Cobra warship swoops in, guns blazing.

No more enemy soldiers.

His commander is standing over him.

Pancho! Pancho! Are you all right?

No, but he survives. The flak vest saves him. Later they’ll give him a purple heart, but for now they bandage him up and send him back into the jungle on a new tank.

"They told me I was going to fight Communism"

Everybody had nicknames in Nam. Joel Jimenez got stuck with “Pancho” because “I was the only Mexican in the unit.”

“They told me I was going to fight Communism. I didn’t know what that was.”

He was raised on “the poor side of town” in Ranger, Texas, a town of about 3,000 people west of Ft. Worth. His mother died in a tuberculosis sanitarium when he was three. His father wasn’t around. He and four siblings were raised by their grandmother who was 67 when Joel was born. He excelled in baseball in high school. By graduation, the war in Vietnam was heating up. One day two men with stripes on their sleeves knocked on the door and Joel was soon on a bus to Fort Polk, La. From there he went to other postings and eventually to that jungle in Kwan Tri.

“Do what they tell you. Pay attention,” his grandmother – his abuela – told him.

Drugs, booze and resentment

“They asked me if I wanted to serve another tour. I had served. I got wounded. I said no.”

After the Army, Joel went to college for a while, worked the rodeo circuit and joined three other veterans from Ranger to work construction at the new DFW airport.

They did some drugs and some booze. A lot of booze.

There was resentment.

“We thought we would probably go home and be heroes" he recalled.

The long war without victory lost favor with many Americans and became politically divisive. Men and women who had served were often shunned. Nobody greeted Joel when he got off the plane. The only support he got was from his family. He turned to alcohol to feel numbness so he could sleep.

“Pretty soon you get to that limit where you’re numb and you can forget those nightmares and flashbacks – ‘Did my bullet kill that lady and her baby laying on the jungle floor?’ It doesn’t go away," he said.

A concussion in a car wreck brought him to Wichita Falls to recuperate in his sister’s home.

Epiphany at the river

One night in 1973 he sits by the Wichita River with a beer in one hand and a cigarette in the other. He sees the Big Dipper. The flashback hits like a thunderclap. The river is gone. The stars are gone. He’s in the jungle.

Thump! Thump! Thump!

When it ends, the Big Dipper has left the night sky.

For Joel, it was an awakening.

“If I go back to the zone, back to Vietnam, I might never come back," he said.

Nam won't let go

A Coke date at the Woolworth lunch counter led to marriage to a petite redhead named Joan. A boy and girl followed. Joel supported his family with work at a credit union, running a storm window business and eventually working for the city of Wichita Falls.

A jovial, outgoing personality became his trademark.

“You saw me in public as happy-go-lucky.”

But Vietnam kept its grip. It affected his kids.

“’I said, put on your clothes, damn it! Let me tell you, this is the way it’s done in the Army. By God!’ -- Why would you talk to a five-year-old that way?” he said.

Sunday mornings at church gave way to hangovers.

The guilt still lingers.

A mission in life

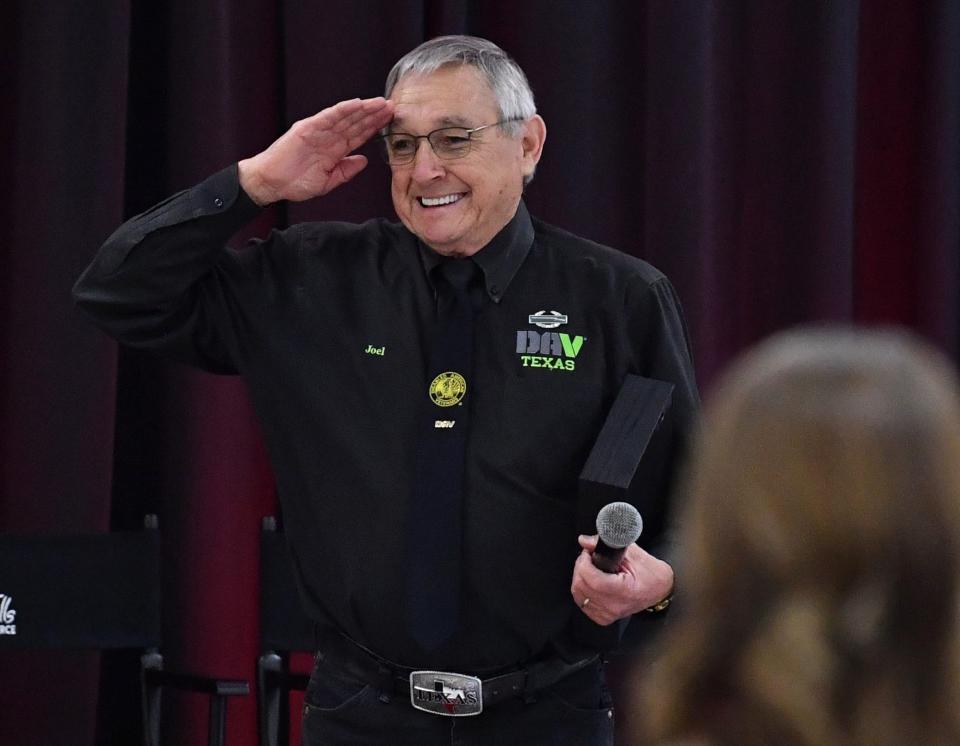

In 1999, World War II veteran George Register told Joel he had a vision in which God said he and Joel should re-form a dormant chapter of the Disabled American Veterans in Wichita Falls.

That was the beginning of a mission. Zero members grew to 700. Joel devoted himself to getting veterans the treatments they deserved.

“I didn’t want them to have the same dreams I had, the same nightmares, when I could give help," Jimenez said. "If I got you medical, compensation would follow.”

The task has been challenging because of government policy toward veterans.

“It’s a ferocious system in this political world," he said. "There are some unfair tactics that are used. They just forgot about us.”

The veterans themselves also are a challenge because of the resentment they received when they came home.

“The Vietnam era guys are not going to step up to the plate to say we’re hurting. They’re afraid to ask because they were denied back then. We just went into our zone and forgot about it.”

He works with them one-on-one, often driving them to medical treatment in Oklahoma City in the DAV van.

Joel joined the ranks of the disabled when he was diagnosed with cancer in 2005, what he says was the result of exposure to the millions of gallons of Agent Orange defoliant the U.S. poured on the jungles.

Cured, he has become a fixture at public events, using his ebullient personality, self-deprecating humor, back slaps and handshakes to bring “these little ol’ veterans” the treatment and respect they deserve.

For his efforts he has been recognized as Outstanding Citizen of the Year by the Rotary Club and in March as Wichitan of the Year by the Chamber of Commerce.

He credits his successes to his faith in God, his family, his wife and the grandmother who raised him.

Vietnam is now 50 years in the past and 9,000 miles away.

The dreams and the flashbacks?

“Yeah. They still come," Jimenez said.

Disabled Americans Chapter 41 in Wichita Falls can be reached at 940-636-7577.

This article originally appeared on Wichita Falls Times Record News: How terror in a jungle became a life's mission for Joel Jimenez