Tension, Deception and ‘Eating Sh*t’: Inside The Black Keys

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In May of 2022, The Daily Beast published an interview with The Black Keys drummer Patrick Carney with the headline, “Why Do The Black Keys Still Feel Like Underdogs?” At the time, Carney posited, “Especially being from Northeast Ohio, it’s hard to win. We’re taught how to lose and to take it on the chin.”

That mentality has apparently stuck. The word “underdogs” is uttered and invoked repeatedly throughout the band’s new documentary—which premiered Monday night at SXSW—as Carney and his bandmate, singer-guitarist Dan Auerbach, contemplate how their humble beginnings in Akron, Ohio, contrast with their eventual success as global rockstars.

Thankfully, since this is a film about The Black Keys—a reliably self-deprecating and facetious pair—it wastes no time noting that with their two-plus decades of critical accolades, world tours, and millions of records sold, they’re not actually underdogs at all. In fact, in the film, it’s rock critic Peter Relic—who in 2002 gave the Keys’ debut album a glowing, career-launching review in Rolling Stone—who wryly points out that Auerbach and Carney always had a roof over their heads and never had to miss a meal growing up. So yeah, they’ve always been fine.

But while they may not be underdogs in the traditional sense—i.e., those who have had to overcome systemic obstacles to reach their goals—director Jeff Dupre’s film argues that their loser mentality has less to do with their Northeast Ohio roots and more to do with the fact that these two men found themselves in a band that should not have lasted for 24 years, mostly because they weren’t really friends for most of that time.

That’s the tension underscoring This Is a Film About the Black Keys, a plain-sailing, 90-minute crash course of their rise to fame that follows the grand tradition of celebrity documentaries warning you that fame isn’t all it’s cracked up to be.

This one begins by rewinding back to Auerbach and Carney’s parallel childhoods in Akron, where they grew up in the same neighborhood but didn’t meet until they were in their early twenties. They bonded over their love of old blues and soul music, like Junior Kimbrough and R.L. Burnside, and that was about the only thing they shared in common. They liken their duo to an “arranged marriage” between two guys who were “willing to eat shit” to achieve their dreams of making and performing music. In this instance, like many a wannabe rockstar before them, “eating shit” meant traversing the U.S. in an old van (later immortalized on their El Camino album cover), performing at grody clubs and sleeping in even grodier motels.

Eventually, the buzz around them got bigger and the crowds followed suit; within a couple of years, they were opening for Sleater-Kinney and Beck on tour. Everything was good until it wasn’t—cue The Black Keys’ first, but not last, hiatus. This is where the film finds its intrigue, as it highlights how Auerbach and Carney’s dueling personalities contributed to that “underdog” narrative.

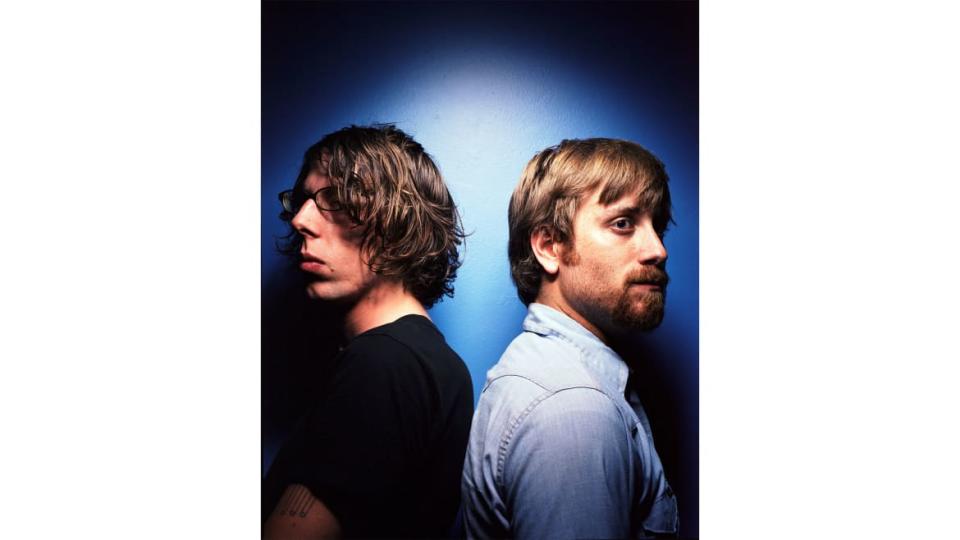

American rock band The Black Keys at Epitaph Records in September, 2003 in Los Angeles, California.

Carney is skilled at the financial and business side of being in a band, but he’s insecure about his musical contributions—that’s Auerbach’s territory as The Black Keys’ lyricist. And as the guy who’s center-stage at the microphone and not stuck behind a drum kit, Auerbach is also the one who more people recognize.

“Ultimately, I’m a side man,” Carney concedes about their dynamic, astutely adding that there’s nothing democratic about a two-man band; everything is inherently a head-to-head battle. Carney eventually started drinking a lot, spurred by insecurity in the band and in his marriage, leading Auerbach to start his own solo and side projects that he kept hidden from Carney, who recalls feeling “very deceived.”

Dan Aurerbach and Patrick Carney of The Black Keys attend the 31st Annual Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame Induction Ceremony at Barclays Center on April 8, 2016 in New York City.

The Black Keys story could’ve easily ended there, but—surprise!—it didn’t. When they finally reunited—at the behest of Damon Dash, who’d called on them to collaborate on a rock/hip-hop hybrid album called Blackroc—they were desperate for a new approach. So they linked up with the buzzy producer Danger Mouse, who had just scored a big hit with Gnarls Barkley’s “Crazy,” and holed up to make their 2010 breakout album Brothers, including a session where, for the first time ever, their sole goal was to write a catchy single. That resulted in “Tighten Up”—an eventual Grammy-winning hit that Auerbach admits he hated at the time—and that song’s familiar whistle intro launches the film’s first “success” montage highlighting a run of late-night shows, SNL, radio plays, and bigger concerts.

After Brothers, they swiftly doubled down on 2011’s El Camino, again chasing catchy hits like “Lonely Boy” and “Gold on the Ceiling,” and again eclipsing themselves as the biggest rock band of the time—cue another montage of the duo winning Grammys, covering Rolling Stone, and graduating to arena shows.

Thus far, this is a straightforward story that has been told before. None of this is particularly new information to Black Keys fans, despite the film’s impressive trove of archival material from their early days. Where the documentary does get interesting is hearing Auerbach and Carney’s commentary on their origin story all of these years later, however limited that may be. In a director’s note provided to the press, Dupre admits that getting the pair to express themselves was difficult (“Pat and Dan did open up and come through in their interviews... in spades,” he writes), which shouldn’t be surprising to fans, especially with Auerbach, who’s the type of guy who keeps his sunglasses on during indoor interviews and who apathetically states that he doesn’t like to reminisce about the past. Even his ex-wife Stephanie Gonis, who’s interviewed on camera for the film, admits she never actually knew him that well despite being married to him for four years. She tenderly calls him “an enigma.”

We get the idea that Auerbach is a frustrating person to be in a marriage with—something Carney can perhaps attest to better than even Gonis can. In one amusing clip from 2012, we see a frustrated Carney on stage during a soundcheck at an arena show, pissed off that his bandmate isn’t there. That’s juxtaposed with a clip of a chilled-out Auerbach shopping for clothes, wondering if he has the chutzpah to rock a studded leather jacket. (He does, apparently; we later see him wearing it backstage.) The guitarist eventually rides into the arena on a small bike, seemingly ignorant to his bandmate’s fury. In interviews, the two separately explain that they don’t talk much or hash things out with each other; they just make music together.

Why Do The Black Keys Still Feel Like Underdogs?

That tension boiled up yet again after their Turn Blue tour in 2014. After some public blows—including Carney’s infamous tiff with Justin Bieber—and some private ones—like Auerbach’s split from Gonis (the film does well to avoid that ugly divorce settlement)—they took another, more extended hiatus. Eventually, as the duo have recounted before, they casually reunited—though it wasn’t a brotherly urge that pulled them back together, but a text message with a photo of a gray Akron sky, which spurred their third conversation in as many years.

Dupre’s film sprints through the last few years, hastily arriving at what all parties insist is a happy ending where Auerbach and Carney’s relationship has gotten to a better, friendlier place. The Black Keys are now gearing up to release their fourth album in five years, following 2019’s Let’s Rock, 2021’s Delta Kream, and 2022’s Dropout Boogie. With Ohio Players, due out on April 5, they got more collaborative, working with heroes like Beck and Noel Gallagher, who both appear in the film’s coda in new studio footage. Carney and Auerbach tell us they want to keep pushing themselves musically but don’t want to burn out again, and that apparently means accepting that they are “just two opinionated, hard-headed people trapped for infinity together.”

If that’s true, they may be eternal underdogs after all.

Get the Daily Beast's biggest scoops and scandals delivered right to your inbox. Sign up now.

Stay informed and gain unlimited access to the Daily Beast's unmatched reporting. Subscribe now.