Ten years ago, Washington put politics aside to save the economy. Could that happen today?

It was the moment Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson had been dreading — and finally, on Sept. 25, 2008, it arrived.

Lehman Brothers had imploded 10 days earlier, instantly transforming the subprime mortgage crisis into a looming economic Armageddon. By the close of trading, the Dow Jones had plummeted 500 points, the largest drop since 9/11. Almost instantly, lenders went on strike, paralyzing businesses big and small. And a chain reaction that started with Wall Street figuring out how to foist trashy loans on overconfident homebuyers — then repackaging and profiting from those loans again and again — now threatened the insurance giant A.I.G., whose failure, a New York Times op-ed predicted on Sept. 15, 2008, could bring on a worldwide financial “collapse [that] would be as close to an extinction-level event as the financial markets have seen since the Great Depression.” (A.I.G. survived, thanks to a $180 billion government bailout later that year.)

Within 72 hours, President George W. Bush and his team had briefed Congress on the danger ahead — at the same time unveiling their politically radioactive plan to prevent another decade of Depression-era breadlines and dust bowls by bailing out the big banks with $700 billion in taxpayer money.

“If we don’t do this, we may not have an economy on Monday,” Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke told the shellshocked lawmakers.

During the frantic week that followed, Paulson personally hammered out the details of the Troubled Asset Relief Program, or TARP, with a small circle of key Democrats and Republicans. A delicate consensus seemed to be forming. Yet Paulson was terrified. At any second, he worried, presidential politics could shatter everything.

“This crisis hit, full force, at the very worst possible time,” Paulson recently told Yahoo News. “It was right in the middle of a national election. Both of the presidential candidates, Barack Obama and John McCain, were essentially running against President Bush, who was very unpopular. If either one of those candidates had come out against what we were attempting to do, I think it would’ve been very difficult to get Congress to act. And then we would’ve had a disaster on our hands.”

To keep that from happening, Paulson was “talking on almost a daily basis” with both nominees. The Democrat seemed to grasp the power and peril of his position. “Throughout the crisis, [Obama] played it straight,” Paulson would later write in his memoir, “On the Brink.” “He genuinely seemed to want to do the right thing. He wanted to avoid doing anything publicly — or privately — that would damage our efforts.”

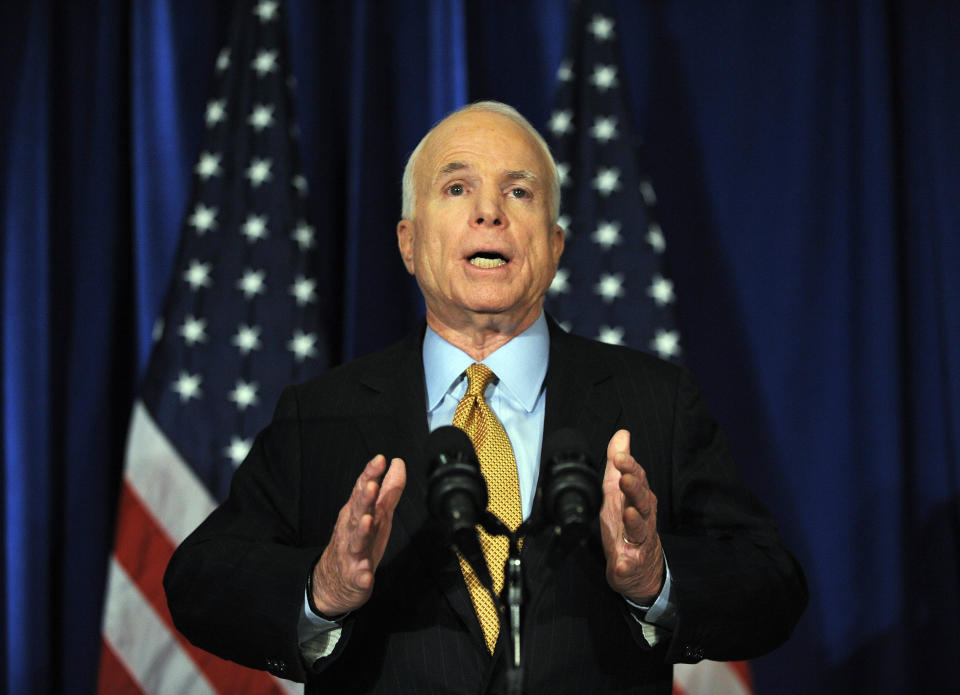

McCain, however, was trailing in the polls. From time to time, seeking to score political points, he would sound a populist note — “We cannot have the taxpayers bail out A.I.G. or anybody else,” for instance — and Paulson would have to call and “encourage [the candidate] to be more careful,” as the treasury secretary later said.

Then came Sept. 24, 2008. The day began with Obama asking McCain, over the phone, to sign a joint statement endorsing Paulson’s TARP plan and urging Democrats and Republicans to cooperate “for the sake of the American people.”

But McCain countered with a more dramatic proposal. While preparing in Manhattan for the upcoming presidential debate, Team McCain had concluded that “this mounting disaster would likely doom [our campaign] unless we could figure out some way to demonstrate that we were helping get it under control,” as the Arizona senator recalled in his 2018 memoir, “The Restless Wave.” McCain’s people were also “hearing reports that House Republicans were reluctant to support” TARP as it was. McCain then upped the ante: How about, he said, if “we suspend our campaigns for a week and postpone the debate scheduled for two days hence, while [you] and I, the White House, and both parties’ congressional leadership [work] out a rescue plan that [can] pass Congress?”

At first, Obama said no. But after McCain went public, Bush reluctantly agreed to host a meeting — and Obama was forced to attend. (“We didn’t favor it,” Bush’s then chief of staff Joshua Bolten tells Yahoo News. “But once [McCain] called for it, we couldn’t really not have it.”) That night, the president delivered his first televised address in more than a year, explaining the crisis, making the case for TARP and extolling the “spirit of cooperation between Democrats and Republicans and between Congress and this administration.”

“In that spirit,” Bush added, “I’ve invited Senators McCain and Obama to join congressional leaders of both parties at the White House tomorrow to help speed our discussions toward a bipartisan bill.”

The president may have sounded confident on TV. But behind the scenes, everyone, including Bush, was thinking what only Obama seemed willing to say out loud.

“It’s important not to inject presidential politics into this, because I think sometimes that prevents things from getting done,” the Illinois senator told reporters.

“My heart was in my throat,” Paulson admits today.

Their fears, it turns out, were justified. At 4 p.m. on Sept. 25, 2008, Bush, Obama, McCain, Paulson and congressional leaders from both parties met in the Cabinet Room of the White House. The clock was ticking. Washington Mutual had collapsed that morning, and Wachovia would follow the next day. A few hours earlier, Republican Sen. Bob Bennett of Utah had emerged from a high-level huddle — “one of the most productive sessions … I have participated in since I have been in the Senate” — and declared that lawmakers would soon have “a plan that can pass the House, pass the Senate, be signed by the president and bring a sense of certainty to this crisis that is still roiling in the markets.”

But the political pressures in the Cabinet Room were too much to bear. Struggling to contain the right-wing backlash that would later fuel the tea party, House Republicans declared they didn’t have the votes. Democrats, arrayed behind Obama, maneuvered to make McCain look like he alone had polarized the situation. And when it finally came time for McCain to speak, the senator at first demurred — then declined to take a stand.

“What’s the Republican proposal?” bellowed Democratic Rep. Barney Frank of Massachusetts. “What’s the Republican proposal?”

Soon everyone was shouting. Bush leaned back in his chair.

“Well, I’ve clearly lost control of this meeting,” he said. “It’s over.”

Fearing that Democrats would say something “inflammatory” to the press, Paulson rushed to the Speaker of the House, Nancy Pelosi, a California Democrat, and dropped to his knees.

“Don’t blow this up,” he pleaded, begging the speaker to save his plan.

“It’s not me blowing this up,” the speaker replied. “It’s the Republicans.”

Four days later, TARP came up for a vote in the House.

Two hundred and five members voted for it; 228 voted against.

***

The story of Paulson’s rescue mission might have ended there. Democrats might have yanked their support and campaigned against Bush’s bailout, leaving a divided GOP to descend into civil war. McCain might have embraced tea party populism, taking a page from Alaska Republican Gov. Sarah Palin, the base-whisperer he had chosen as his running mate. And as Bush himself warned that day, “this sucker” — meaning the entire global economy — “could go down.”

Yet that didn’t happen — none of it. Both Obama and McCain helped corral votes, and on Oct. 3, 2008, a revised TARP passed the House. It was a pivotal moment in one of the most challenging and consequential seasons in American history: a four-month span that started with the biggest crash since the 1920s; then progressed through the final phase of a pivotal election, with the most unpopular president in recent memory on his way out and his successor yet to be chosen; and continued into a transition period that required a lame-duck president from one party and a Congress and a president-elect from the opposing party to formulate and coordinate an unprecedented response to an unprecedented catastrophe — despite competing political incentives, opposing political philosophies and resistance from both the right and the left.

And somehow they did it. Together.

Now, 10 years after that calamitous Cabinet Room meeting, bipartisanship has become the least fashionable principle in American politics. Most Republicans had already abandoned the idea by the time they impeached President Bill Clinton in 1998; the ones who hadn’t certainly had by 2016, when they declined even to consider Obama’s final Supreme Court nominee, Merrick Garland. Donald Trump — a man who propelled himself into politics by insisting that Obama was born in another country — has refused as president to reach out in any way to the millions of Americans who disagree with his views, dismissing Democrats as “weak,” “pathetic,” “crooked” and “losers.” Progressives, meanwhile, have responded in kind, mocking the sort of “no labels” talk that used to dominate D.C. dinner parties — and Obama’s own speeches — as woefully naive, if not plain dumb, and pushing instead for a politics that excites the left and leaves compromise behind.

This polarization is, in part, a product of the epochal events of late 2008 and early 2009. Nobody liked Bush’s bank bailout. Few were thrilled about Obama’s stimulus. The rich got richer; everyone else fell further behind. Americans lost trust in institutions. Rage on the right gave rise to the tea party; rage on the left gave rise to Occupy Wall Street. And then there was Trump.

Every think piece pegged to the 10th anniversary of the crash, and there have been plenty, explains where our system — our politicians, our policymakers, our government — went wrong: not enough foreclosure relief for ordinary homeowners; too many blank checks for big banks and their greedy CEOs. It’s all true, more or less. But what’s also true is that the last time the world needed saving, it was our system that saved it.

“We saw some of the very worst human behaviors and flaws in our policies and government contributing to the crisis,” Paulson now says. “But I think the way the system worked — the way it all came together in the last several months of 2008 and into the transition — really shows the best.

“As I look at it now, that was the last time Congress came together on a bipartisan basis — a truly bipartisan basis — to deal with a consequential, controversial topic.”

The kind of bipartisanship Paulson is recalling isn’t kumbaya. It isn’t a gauzy campaign slogan; it isn’t “no labels.” In reality, it was hard-nosed and unsentimental — all ugly deals and brutal sacrifices. Eventually, dozens of lawmakers lost their jobs, and the whole thing clicked only at the eleventh hour — a last resort as the economy was coming undone.

McCain’s example is revealing. Throughout that fall, he kept threatening to go rogue. But ultimately, he resisted the temptation, putting the fate of the country above the fate of his campaign.

“I had some very, very difficult conversations with [McCain],” said Paulson. “It would’ve been very easy for him to go the populist route — for him to attack what we were doing as bailouts. And though he wavered a number of times, at the end he did not. At the end, he helped us with TARP rather than hurting us. And I’m just increasingly grateful for that.”

The question now, however, is whether even that kind of bipartisanship — that fitful yet ultimately functional response to a crisis — is beyond us.

Today, a decade after the crash, the economy is humming. Unemployment is low. But in the shadows, debt is mounting, and someday the next crisis will hit. When it does, how will our current system — our so-called fake-news feeds; our ever more polarized Congress; our chaotic, expertise-averse White House; our me-first president — respond?

Joshua Bolten, for one, is worried.

“I’m very concerned about our system,” admits Bush’s former chief of staff. “You have to consider that with all the turbulence we’ve been through in the — what is it now? — 20 months of the Trump administration, nothing external has actually gone wrong. There have been no crises.

“To the extent there have been foreign policy challenges, they’re the same ones that all recent presidents have faced,” he continues. “There have been some natural disasters, but manageable ones. And there have been no economic crises.

“The 2008 financial crisis was by no means an idyllic example of bipartisan cooperation. But on the really tough stuff that needed to be done, Democrats and Republicans did come together to take necessary but unpopular actions. I have to question whether that’s possible in today’s environment.”

Bolten sighs. “I hope it is,” he finally says. “But I’m not confident.”

***

If you talk to people like Bolten — people who spent 2008 and 2009 in the middle of the maelstrom — most of them say the same thing. The reason is simple: They saw firsthand what it took to avert catastrophe back then, and they see a lot less of it in Washington today.

As the 10th anniversary of the crash approached, Yahoo News reached out to a number of key players from that period. Some are still boldfaced names (Paulson, Pelosi, Frank). Some had starring roles at the time (Bolten, TARP czar Neel Kashkari, top Bush economic adviser Keith Hennessey). Some remained behind the scenes (Obama legislative liaison Phil Schiliro, TARP chief investment officer Jim Lambright and key strategists for congressional leaders).

Many of these insiders disagreed on who deserves credit and blame, both how much and for what. But all of them agreed on three essential elements that saved us from a second Great Depression then — and now, a decade later, seem to be in short supply.

The first is leadership. “Leadership” is a word so overused in political op-eds and business bestsellers that it’s been sapped of much of its meaning. But at the pinnacle of American public life, as “CBS This Morning” co-anchor John Dickerson recently wrote in his introduction to Yahoo News’ documentary series “When Presidents Lead,” it has been “defined by men [and women] who on at least one occasion focused their energies, and chanced their political fortunes, on something larger than their self-interest.”

“Instead of the easy win, or easy out, they took the long view,” Dickerson concluded.

According to those closest to him at the time, Bush displayed precisely this sort of leadership during his final months in office. On Thursday, Sept. 18, 2008, the president met with his team — Paulson, Bernanke, Securities and Exchange Commission Chairman Christopher Cox and top policy adviser Joel Kaplan, among others — in the White House’s Roosevelt Room. When Lehman had fallen on Monday, the administration had let it fail. But when A.I.G. followed on Tuesday, it got a bailout. The moment had come to settle on what Paulson called “a more systematic approach” — “before we bled to death,” as he put it.

It was to be, in Bolten’s words, “the most significant economic meeting of Bush’s presidency.”

The president cut right to the chase. “Is this the worst crisis since the Great Depression?” he asked.

“Yes,” Bernanke answered. “We’ve not seen anything like this since the 1930s — and it could get worse.”

By the end of the meeting, Bush had approved Paulson’s $700 billion rescue plan — a decision, Bolten says, that “couldn’t have been easy” for him.

“Bush knew the political consequences would be devastating,” Bolten says. “He knew no Democrat would like the idea of bailing out the banks, and he knew most Republicans would hate the idea of a bailout for anybody. So the remaining few percent of the electorate that was still supportive of him, he’d probably alienate; beyond that, he knew the decision would be damaging to his party, which would have to take responsibility. He knew that. But Bush was convinced it was absolutely essential and there was no other choice.”

As the meeting broke up, Bush pulled each participant aside for a private word. “Don’t worry,” he said. “We’re doing the right thing. We’ll get through this. Go get some rest.”

Afterward, he walked back to the Oval Office with Bolten and Dan Bartlett, his longtime strategist. History was on his mind.

“If this is Roosevelt or Hoover,” he mused, “for damn sure I’m gonna be Roosevelt.”

By all accounts, this is how Bush operated throughout the crisis. As Paulson later said in his memoir, Bush’s goal was “to leave the country in as strong a financial position as possible for his successor.”

“Skeptics may doubt me, but this is the truth: In any accurate recounting of the financial crisis, you won’t find the president playing politics with these decisions — not one instance,” Paulson says.

Even Frank, a fierce Bush critic who then chaired the House Financial Services Committee, praises the president for privileging policy over politics. “I do give George W. Bush credit,” Frank tells Yahoo News. “He allowed Bernanke and Paulson to break with Republican ideology [and] gave them the license to ignore congressional Republicans” who were threatening to revolt.

Bush’s attitude trickled down. According to Paulson, the president made it clear that “one of the reasons he brought me on as treasury secretary is he wanted me to work with Democrats and Republicans. And from the day I showed up, he did everything he could to encourage me” to do just that.

Likewise, Paulson forgot to confirm Kashkari’s party affiliation until after he hired him at Treasury. “Paulson interviewed me, talked about what he wanted to do,” Kashkari recalls. “And at the very end, he went, ‘Oh, by the way, are you a Republican?’ I said, ‘Yes, I am a Republican.’ And said, ‘OK, good. The White House will care.’ But he couldn’t have cared less. And I think he and Bernanke brought that spirit to the financial crisis. They really just wanted to get the best ideas. Politics came way, way later.”

Eventually, as the administrator of TARP, Kashkari made sure that “everybody we hired was nonpolitical, with a career appointment, so that we could hand the new administration — whoever it was, whether McCain or Obama — a fully functioning office with very little turnover.” By design, Kashkari was “literally the only political appointee in the Office of Financial Stability.” And though Kashkari still identified as a Republican, he voted that November for Obama because he was “struck by the depth of understanding that [he] was showing about the financial crisis. It was remarkable.”

This largely apolitical approach, in turn, bridged administrations. “Regardless of who wins the election, the issue of transition to the next administration is going to be very important,” Obama said that fall. “And it’s going to have to be executed with a spirit of bipartisanship and cooperation.”

Which isn’t to say that Obama & Co. eliminated politics from their calculations. Unlike Bush, a lame duck with little but his legacy left to consider, the Illinois senator still had to win an election and marshal as much political capital as possible for his agenda. Such considerations came into play when Obama railed against Republican deregulation, which he saw as the cause for the crash; they came into play when he pushed back on executive compensation and for homeowner relief; they came into play when he cut off communication with Paulson immediately after the election, leaving the outgoing treasury secretary feeling “a little bit abandoned” — but also “free,” in Paulson’s words, “to do the difficult, messy, unpopular things we needed to do” without “implicating the new president.”

The truth, however, is that “any new administration is going to come in with a political lens,” says TARP’s Lambright; an incoming president can’t afford to disregard rhetoric and optics the way an outgoing president can. Yet what ultimately impressed insiders was how Obama, like Bush, set aside his immediate self-interest to pursue the greater good.

When the first TARP vote failed and the second was looming, for instance, Paulson called Obama directly. (“I think I’m going to be president, and I don’t want to inherit an economic wasteland,” Obama had told him in September. “If you ever think the system is ready to go down, and I can be helpful, let me know.”) Afterward, Obama personally phoned “more than a dozen members of Congress,” according to Schiliro, his legislative liaison, “just trying to make the argument that ‘this may be unpopular, it may eventually be a politically difficult thing for you, but it’s the right thing for the country.’”

“A cynical approach — the political thing to do — would be to make sure the full impact of the crash is felt before enacting a solution,” Schiliro said. “But no one ever thought that way. We treated this as almost as if we were already in the White House.”

In November and December, as Washington scrambled to avert the collapse of the Big Three automakers, Obama was more active and assertive than any other president-elect in memory. He pressed Bush at a private meeting to support government help, then mediated between House Speaker Pelosi and Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid when they were at loggerheads over funding; in the following weeks, Obama directed his advisers to open lines of communication to Republicans as well. By then, a White House aide told the New York Times, Bush and Obama were speaking “more than any of us know.”

During the transition, Obama tried to strike a careful balance: on the one hand, prepare for power; on the other, keep an appropriate distance. “Do everything you can to help the process along,” Obama instructed his team. “But don’t get in the way.” His mantra was “there’s only one president at a time.”

Occasionally, the president-elect’s approach confused or even worried Bush’s people. When White House officials summoned their Obama counterparts to Paulson’s office for an urgent meeting the Sunday after Thanksgiving, their goal was to coordinate on the auto bailout — but Team Obama didn’t bite.

“Basically, we were saying, ‘We’ll give you a preview of what the loan terms are, we’ll give you the opportunity to approve or disapprove, to work with us and to find someone jointly acceptable, an auto czar, to oversee the implementation,’ just to make sure everyone knows that the terms and conditions of the loans will be enforced,” recalls Hennessey, director of Bush’s National Economic Council. “They said, ‘Great, thanks. We’ll take it back to the boss.’ And then they never gave us an answer, even though we kept asking. So eventually, we just went ahead.”

Yet despite these hiccups, the end result, says Hennessey, was “a tremendous amount of policy continuity.” Just before Thanksgiving, Obama nominated for treasury secretary one of Paulson and Bernanke’s closest collaborators: Timothy Geithner, then the president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. Congress released the second half of TARP funds to Obama four days before his inauguration; Geithner asked Kashkari to run the program for a few more months, and Lambright stayed on as well. In early 2009, Obama refused to nationalize banks such as Citigroup — against the wishes of his more liberal advisers. Even though the new president adjusted Bush’s auto bailout, he didn’t abandon it. “[Autos] took a little longer than we thought, but at least there were people on the transition engaged with us, learning the issues, learning the history and preparing themselves to own it,” Lambright says. “I thought those people were impressive, smart, serious and easy to work with. Given how politics works and how life works, the transition was actually pretty good.”

Paulson agrees. “Obama inherited a bunch of programs that were very unpopular and a base that was angry at bankers and wanted to see them punished,” he says. “So I give him a lot of credit for continuing with policies that were very unpopular, adapting them in ways that were unpopular and taking additional measures that were also unpopular.”

“It was amazing leadership, I think, from both presidents,” Paulson concludes. “They both put the country first.”

***

Two additional factors, meanwhile, ensured that leadership at the top translated into results on the ground: relationships and trust.

Many of the unlikely relationships that shaped the period were forged in the trenches. “My best Democratic collaborator was Rahm Emanuel,” says Bolten, referring to the brash Illinois congressman and Democratic caucus chairman who would succeed him as chief of staff under Obama. “A more partisan figure probably did not exist. But he’s also a patriot, and if you can last through the first 60 seconds of F-bombs, he had the best, most constructive advice. Nobody worked harder to pull the votes together for TARP.”

Yet the most important bonds were the ones that predated the crash — particularly the connection between Paulson and Democratic House Speaker Pelosi.

“We have a political system that doesn’t like to come together and deal with controversial things,” Paulson says. “But in 2008 and 2009, I don’t think people just magically came together because there was a crisis. I was very fortunate that I had a year before the crisis hit where President Bush encouraged me to work with members of Congress. I worked with them on getting trade deals done. I worked very closely with Nancy Pelosi on a stimulus bill [in early 2008]. We’d had plenty of time to work together.”

The stimulus Paulson is referring to was, as the Washington Post put it at the time, the product of “arduous, late-night negotiations” — “a work of difficult compromise” that packaged $168 billion in economic relief for middle- and lower-income Americans into GOP-friendly tax rebates, then passed a Democratic Congress and was signed into law by a Republican president.

Pelosi discovered during these negotiations that Paulson was someone she could work with — an honest broker. “He’s a person of integrity, he’s a person of knowledge and he had the confidence of the president,” Pelosi tells Yahoo News today. “We would meet in this room called the ‘Education Room.’ It was where lawmakers used to go in the evening and play cards and have a little drink. The press would never know we were there — nor would our members, more importantly. We could just slip into that room and have our conversations.”

Paulson was equally impressed with Pelosi. “Out of that experience, the secretary, and the president for that matter, understood that Pelosi, notwithstanding her serious disagreements with the administration not only on Iraq but also over economic policy, was nevertheless willing to engage legislatively and politically,” says John Lawrence, Pelosi’s chief of staff at the time. “And I think the fact that she was able to bring along her caucus and deliver votes and negotiate” — unlike her Republican counterpart, Minority Leader John Boehner, who struggled to keep restive conservatives in line — “I think that really did earn Paulson’s trust.”

The upshot, Lawrence says, is that when Lehman collapsed, Paulson and Pelosi “didn’t have to face this terrible crisis right from the get-go with no relationship established.” Because they were already working together on big problems before the crisis, they were ready to meet the challenge when it finally came.

This sort of professional, bipartisan respect — some baseline level of trust, not only between individuals, but also among, and in, our institutions of government — is the final ingredient that made the rescue mission of 2008-09 possible. And like the others, it also seems to be missing today.

Pelosi is still doing what she was doing 10 years ago — leading the House Democratic caucus. But she believes that, under Trump, the norms of the presidency have changed. “Back then, we had the confidence of the president, we had the confidentiality of the discussion and we had a stipulation of fact as to what we wanted to achieve and what the numbers were,” Pelosi recalls. “But these are all things that are very lacking in this administration. In a negotiation, you have to know what the numbers are and recognize that it’s not an opinion — it’s not subjective.”

Schiliro, Obama’s legislative guru, elaborates. “Trust is the bedrock of reacting to crisis, because if and when something goes wrong, Congress needs to make sure the information it’s acting on is accurate,” he says. “But when a president says, ‘You can’t believe anything except what I say’ and attacks the Justice Department and other entities of the government — when there are attacks on what people know to be true — then that creates a trust issue when Congress is relying on the White House for factual information in a crisis.

“There needs to be, no matter who is in control of the House or the Senate, an institutional integrity,” Schiliro says. “As this institutional integrity gets hollowed out — and as factual information gets hollowed out to serve political purposes — it makes it very hard to react quickly. This administration may have fundamentally changed the dynamics. And while it doesn’t mean the next crisis will be fatal, it does mean the degree of difficulty will be even higher.”

***

In retrospect, the most terrifying moment of 2008 wasn’t the Cabinet Room meeting that unraveled behind closed doors. It’s what could have come next. Obama could have sprinted to the television cameras to spin events in his favor; McCain could have done the same. And the partisan chaos that was, at that moment, contained to the corridors of the White House could have spread through Washington like wildfire.

“The fear was that they were going go out and say, you know, ‘We don’t think that TARP is a good idea’ or ‘We don’t think that we’re going to be able to reach agreement on a TARP,'” recalls Hennessey, the director of Bush’s National Economic Council. “Had they said that, it would have unleashed the hounds for all the partisanship to come out. You’d never be able to corral everybody and restore the cooperation that you need to get a bipartisan vote. So had they gone after the cameras at that point in time, I think we would’ve lost the TARP. It was essential that they didn’t.”

In the end, of course, they didn’t. Paulson ran to Pelosi and Obama; Bush’s legislative chief, Dan Meyer, cornered Boehner and Senate Republican leader Mitch McConnell; McCain retreated to his hotel. The hounds of partisanship were kept at bay.

And for the most part, that’s where they remained — at least until Obama became president, liberating Republicans who had reluctantly cooperated with Bush’s unpopular rescue plan to pursue their own political self-interest by opposing and obstructing the new Democratic president’s efforts to continue the nascent recovery.

“When we were in the congressional majority and George Bush was president, he got extraordinary cooperation,” says Frank. “And not only did you have this cooperation across partisan lines, it was happening at the most politically fraught time in the American calendar, about two months before an election. So if people want to know when bipartisanship ended, there’s a date: Jan. 20, 2009. The contrast between what the Democratic members of Congress did with Bush and how the Republicans reacted to Obama is enormous.”

On inauguration night, as Obama celebrated at various balls, a group of 15 top Republican lawmakers met with former House Speaker Newt Gingrich and messaging maven Frank Luntz at Washington’s high-end Caucus Room restaurant to plot their comeback. “If you act like you’re the minority, you’re going to stay in the minority,” said California Rep. Kevin McCarthy. “We’ve gotta challenge them on every single bill.” As Robert Draper later reported in his book “Do Not Ask What Good We Do: Inside the U.S. House of Representatives,” the group agreed to “show united and unyielding opposition to the president’s economic policies.”

“You will remember this day,” Gingrich said on the way out. “You’ll remember this as the day the seeds of 2012 were sown.”

A week later, Obama was scheduled to visit Capitol Hill to discuss his stimulus plan with House and, later, Senate Republicans. But in a meeting that morning, then-House Minority Leader Boehner exhorted his troops not to support the bill — and House Republicans wound up announcing their opposition before the president had even left the White House. When the second half of TARP was released to Obama earlier that month, only six Republican senators had voted in favor, 28 fewer than had voted to release the first half of TARP to Bush; when Obama’s stimulus package came up for a vote in February, the entire House Republican caucus voted against it.

“The single most important thing we want to achieve is for President Obama to be a one-term president,” said McConnell the following October.

As a result, partisanship metastasized like a cancer over the course of the decade that followed the crash.

But ultimately, polarization is not the root cause of our dysfunction. Nor is Trump. The bigger problem is what made such partisanship so alluring and Trump possible. Today, all the incentives in American culture point to self-expression and individualism; most of the structures that once encouraged collaboration have crumbled or been torn down. We lack rewards for self-sacrifice and penalties for selfishness.

The internet and the iPhone have atomized media — and all of us — into little islands. The surest path to significance is to shout to be heard, to stand out, to not be like the others. Likes and followers now constitute success. And in the rush to accumulate these things, we forget to create a context in which people can solve problems.

To put it another way: If that calamitous Cabinet Room meeting happened today, no one would need a television camera to unleash the hounds of partisanship. They could simply pick up their phone and tweet. (It’s hard to believe, but Twitter, founded in 2006, was still a niche platform in 2008.)

It’s true that elites have failed the country in many ways. But such failures stem, in part, from the growing belief that elites shouldn’t exist at all.

To make progress and overcome challenges, people must work together, over time, in a sustained way. And when disagreements arise, as they always do, we need a forum in which to work them out.

Political parties used to serve this purpose, enabling collective action in both campaigns and government. But over the last half century, well-meaning officials have reformed parties into shells of what they once were, and in 2016, Trump exposed how hollow they’ve become. Only a third of Republican primary voters cast their ballots for Trump that year — yet party leaders could do nothing to stop him from seizing the nomination.

The old system of insider politics is dead. We now want our politics to be transparent, immediate and brand-based. We consider parties irrelevant, and we don’t seem to care how our politicians can possibly accomplish anything once an election ends.

The new politics rewards authenticity, which has its merits. But to cut through the noise, proposals and platforms are growing increasingly simplistic; to promote them, politicians are increasingly behaving in ways calculated to provoke outrage. This approach rallies the base — and makes for good cable TV — but when it’s time to govern, not much gets done.

There are signs, however, that the American political class is waking up to the dangers of an ever more selfish public square.

“The central question in our democratic age is this,” says Jeffrey Rosen, president of the National Constitution Center, in a recent issue of the Atlantic magazine dedicated entirely to “the crisis in democracy.” “Is it possible to slow down the direct expression of popular passion?”

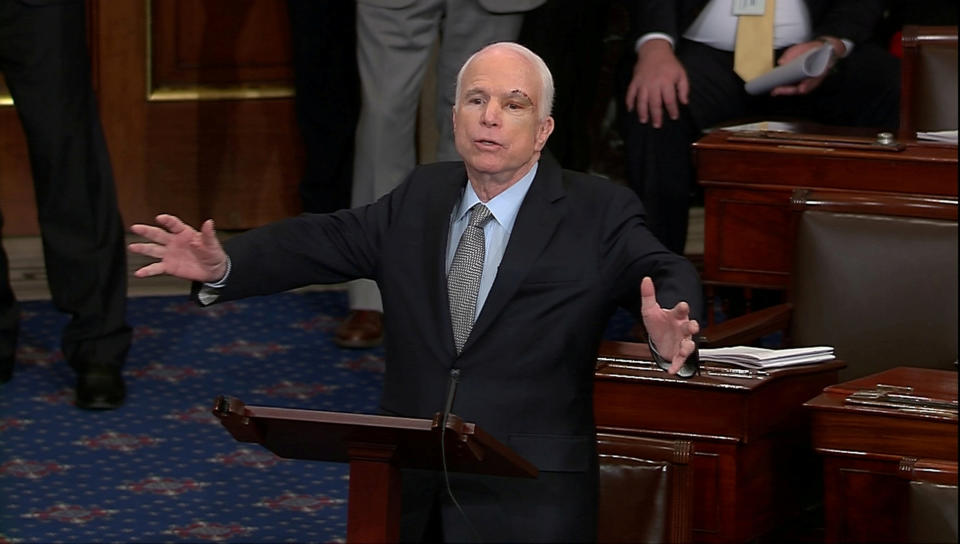

And McCain, in one of his last speeches on the floor of the Senate, urged his fellow senators to rise above the politics of division and immediate gratification.

“Our system doesn’t depend on our nobility,” McCain said. “It accounts for our imperfections, and gives an order to our individual strivings that has helped make ours the most powerful and prosperous society on earth. It is our responsibility to preserve that, even when it requires us to do something less satisfying than ‘winning.’ Even when we must give a little to get a little. Even when our efforts manage just three yards and a cloud of dust, while critics on both sides denounce us for timidity, for our failure to ‘triumph.’

“I hope we can again rely on humility, on our need to cooperate, on our dependence on each other to learn how to trust each other again and by so doing better serve the people who elected us. Stop listening to the bombastic loudmouths on the radio and television and the internet. To hell with them. They don’t want anything done for the public good. Our incapacity is their livelihood.”

The problem, however, is that those bombastic loudmouths are now the ones with the power. Fox News and MSNBC are today’s “establishment,” along with the special-interest groups enforcing orthodoxy on their single issue of choice and the megadonors propping up candidates who run in cynically gerrymandered districts and owe nothing to a party structure that once might have prepared them for office.

What we lack are the old counterweights — an organized and robust party system, a trusted media, a network of nonpoliticized institutions — that can constrain and redirect public officials from responding only to the most extreme or persuasive voices. Until that changes, or until voters again decide to reward the less entertaining virtues of selflessness and teamwork, our politics will probably continue to disintegrate.

And when the next crisis comes, we may all pay the price.

_____

Read more from Yahoo News:

Clinton aide: We didn’t recognize ‘full scope’ of Russian interference on social media

Fiona Hill, Trump’s top expert on Russia, is quietly shaping a tougher U.S. policy

A Rosenstein departure could raise new conflict-of-interest issues for Justice Dept.

Photos: Anti-Kavanaugh protesters gather on Capitol Hill after 2nd allegation of sexual misconduct