Taxes, Nike, and GDP — what you need to know for the week ahead

With stocks at record highs, investors will keep their focus on tax reform and the goings-on in Washington, D.C. for the final full trading week of the year.

Late Friday, Republican leadership released a draft of its plan to cut corporate taxes that could come to a vote in both houses of Congress next week.

And while activity on Wall Street is certainly winding down into year end, the economic and earnings calendars in the week ahead are perhaps not a barren as one might expect. The economics agenda gives us a third estimate on third quarter GDP growth, as well as readings on consumer sentiment, and a bevy of housing market data.

And on the earnings side, results are expected from FedEx (FDX), Nike (NKE), Micron (MU), Darden (DRI), Bed, Bath & Beyond (BBBY), and Accenture (ACN) among others.

Bitcoin (BTC-USD) will also remain a big storyline in markets with the CME Group set to launch Bitcoin futures on Sunday evening, joining the Cboe as another major financial exchange offering derivatives on the digital currency.

Economic calendar

Monday: Homebuilder sentiment, December (70 expected; 70 previously)

Tuesday: Housing starts, November (-3.2% expected; +13.7% previously); Building permits, November (-3.1% expected; +5.9% previously)

Wednesday: Existing home sales, November (+0.7% expected; +2% previously)

Thursday: Philly Fed manufacturing, December (20.8 expected; 22.7 previously); Third quarter GDP, third estimate (+3.3% expected; +3.3% previously); Personal consumption, third quarter (+2.3% expected; +2.3% previously); Initial jobless claims (234,000 expected; 225,000 previously); FHFA home price index, October (+0.4% expected; +0.3% previously)

Friday: Personal income, November (+0.4% expected; +0.4% previously); Personal spending, November (+0.5% expected; +0.3% previously); “Core” PCE, year-on-year, November (+1.5% expected; +1.4% previously); Durable goods orders, November (+2.2% expected; -0.8% previously); New home sales, November (-5.1% expected; +6.2% previously); University of Michigan consumer sentiment, December (97.2 expected; 96.8 previously)

Jeremy Gratham’s big bet

Jeremy Grantham, the market veteran who serves as chief investment officer at GMO, the firm he helped co-found, has a new big bet — emerging markets.

In his latest quarterly letter, Grantham writes that currently, the long-term outlook for U.S. stocks is “dismal”; he expects 2.5% real average annual returns for the S&P 500 over the next 20 years and about 3.5%-5% real returns for international stocks over that period.

And in the face of what is likely to be a downbeat period for investors — and Grantham is particularly concerned about pension funds that won’t hit their long-term targets with returns of this magnitude — Grantham sees now as the time for investment managers to use up what he calls “career risk units.”

In the investment management business, investors often talk about career risk as shorthand for making bets that are not only non-consensus, but likely to result in clients abandoning your services if this bet goes wrong. The herding behavior often seen on Wall Street, particularly when it comes to things like expectations for the stock market in the year to come, is an example of folks hedging career risk. If you’re wrong in the same way as everyone else, it is less remarkable than being wrong alone.

With this framework in mind, Grantham argues while individual securities have become more efficiently priced through time, asset classes have not. And so the only value managers give to clients when it comes to asset allocation is to make big bets — and be right.

“If you mean to offer a useful asset allocation service to institutions, one that is designed to beat benchmarks and add value as well as lower risk, then you must make bets,” Grantham writes.

“And when there are great opportunities, which is all too often not the case, you must make big bets. If you mean only to tickle the allocation with slight moves, you may have a good framework for coffee time conversation with clients but you are not going to make a difference. Ever. If you are not prepared to put considerable career or business risk units on the table (and be prepared to persuade the clients’ managers to do the same!), for example, in a classic equity bubble like 2000, or a classic housing bubble with associated junk mortgage paper in 2007, then you should not offer the service.”

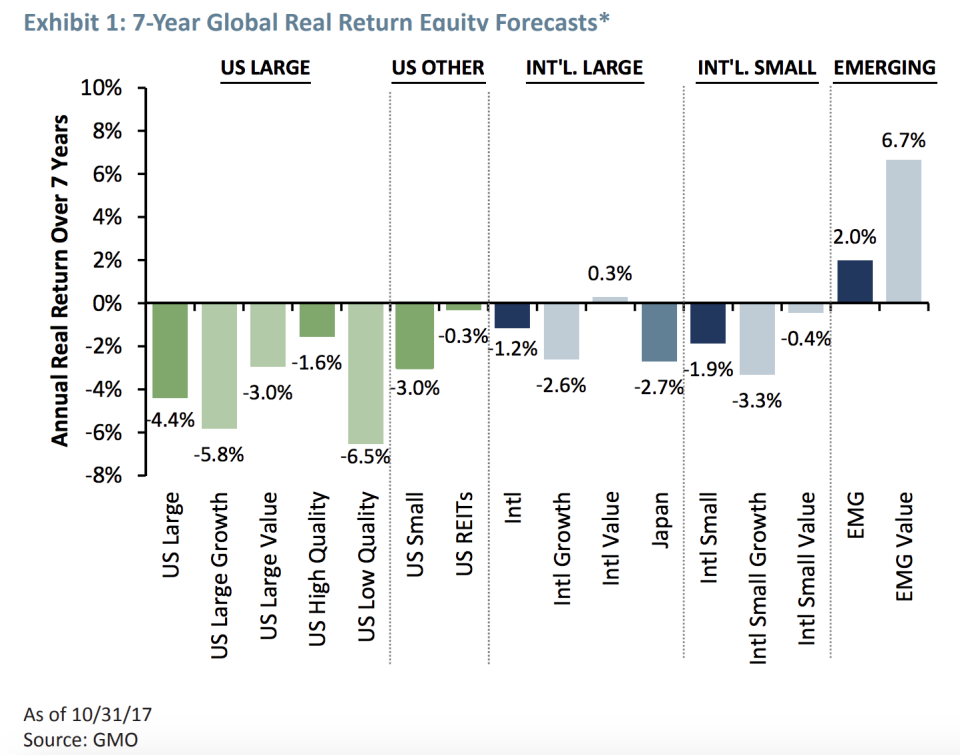

And so looking at the current pricing of various asset classes relative to history, emerging markets offer investors by far the greatest potential returns going forward, according to GMO.

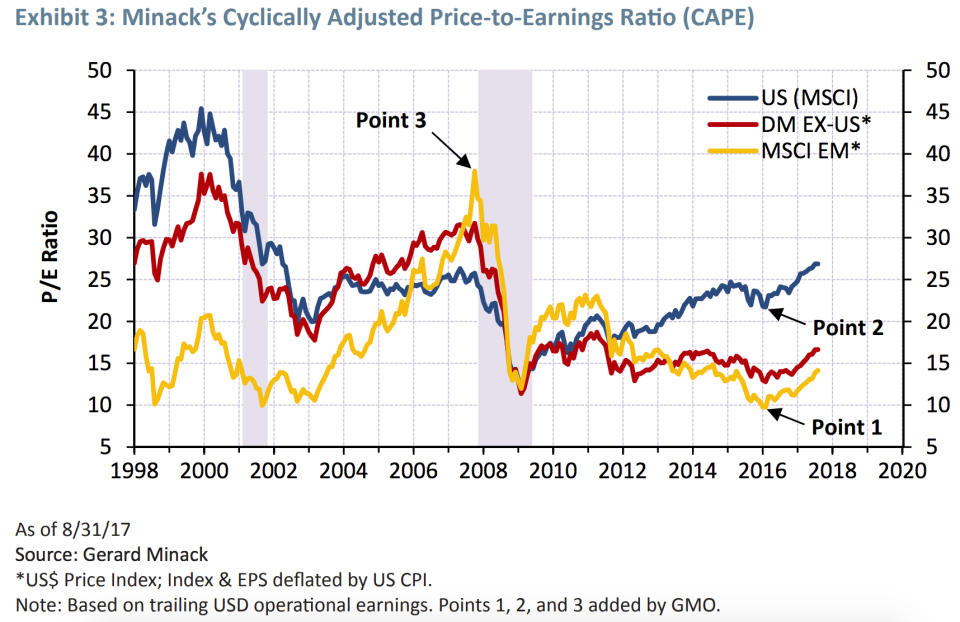

And while many skeptics would note that emerging market stocks got hit even harder than developed markets during the financial crisis, emerging markets were more expensive than developed market stocks in 2007.

An updated look at emerging markets reveals that the sector’s CAPE ratio was lower than it was after the financial crisis within the last 18 months and is still 65% below its all-time high. Meanwhile, U.S. stocks are now more expensive than they were ahead of the financial crisis.

Now, many investors including Warren Buffett have argued that stocks valuations must be taken in the context of interest rates, with lower interest rates making stocks relatively more attractive given lower return profiles in fixed income.

But Grantham’s overarching point is that in the context of markets where almost everything looks expensive, relative value is what will best serve investors in the more challenging periods he expects will come to markets.

“Back in 2000 we were saying that we were very bearish on the US but also very confident that small caps would outperform,” Grantham writes. “The client response was either bewilderment or shock at our inconsistency.”

Yet when the dust settled after the dot-com bubble burst, small cap stocks were down 40% less than their large cap counterparts while small cap value stocks actually eked out a positive return.

“In major rapid declines, relative (and absolute) value indeed plays a very large role alongside beta,” Grantham writes.

Which is a way of saying that while market declines will bring volatility to most all asset classes, what looks cheapest before a crash stands the best chance of looking okay on the other side.

—

Myles Udland is a writer at Yahoo Finance. Follow him on Twitter @MylesUdland

Read more from Myles here: