The Survivor

NAHAL OZ, Israel—In 1951, when the state of Israel was three years old, a small group of young soldiers set up camp not far from the border with Gaza, which was then under Egyptian control, and called the site Nahal Oz, meaning riverbed of valor.

The Armistice Agreement of 1949 ensured quiet at the border, and by 1955, the soldiers were gone and Nahal Oz had become a civilian kibbutz, or farming collective.

Shalom Yospe has made it his home since 1965, when he was 19 years old, recently discharged from the army, and embarking on what he calls “this, my sweet life.”

He is a happy man. During his years at Nahal Oz he has cycled through several careers (diving instructor; chief inspector of buildings for a major car importer) married, had four children, divorced, endured a bout of cancer and now, when not engaged in his favorite activity, which is adventure traveling, he enjoys observing the kibbutz’s flourishing green lawns from the comfort of his porch, and petting his neighbor’s dog, Tony.

A bearded Shalom Yospe attending event at Nahal Oz kindergarten in 1981 or 1982.

“Look at him,” Yospe says admiringly. “He’s the best-looking dog on the kibbutz. He’s the Brad Pitt of all our dogs.”

Yospe recently returned from a four-wheel-drive tour of Kyrgyzstan. Before that, he toured Inner Mongolia.

Nahal Oz lies a scant half mile from Israel’s border with Gaza, which today is ruled by Hamas, an Islamist paramilitary group. These days, it is mostly known for the rockets and missiles that land here.

The international community defines Hamas as a terrorist organization and Israel and Egypt, the two countries that flank the enclave, have imposed a blockade since 2007, when Hamas wrested control of Gaza from the Palestinian Authority, which is based in the West Bank.

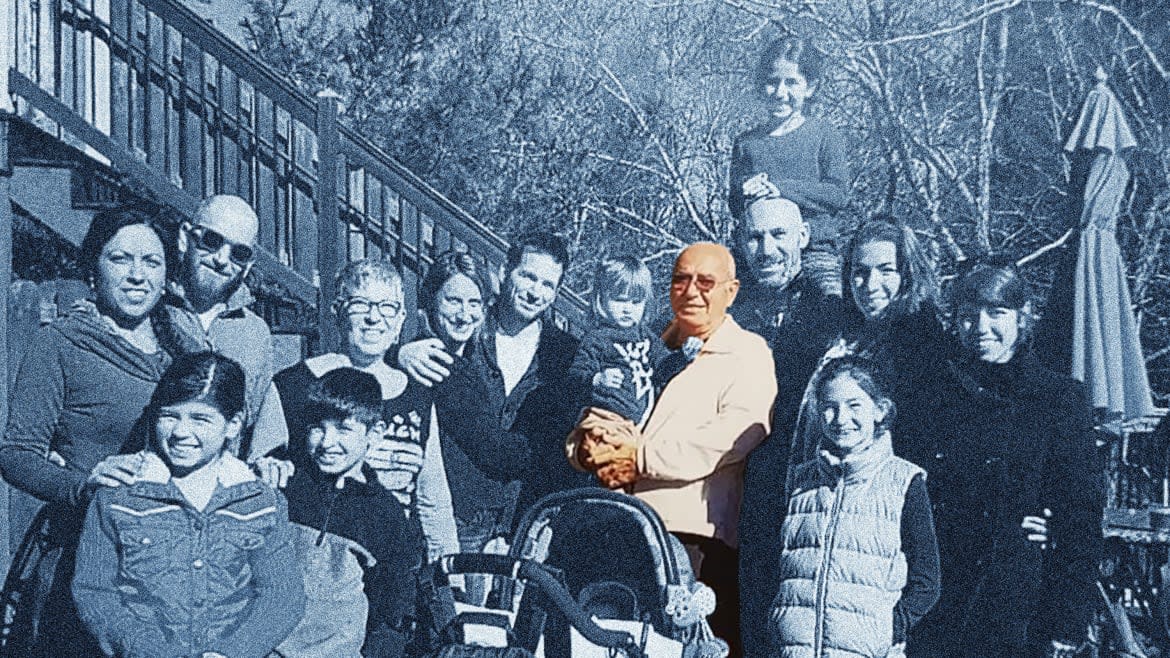

Yospe clan enjoying lunch on grandpa Shalom's beloved porch

The past dozen years have been defined by periodic descents into battle, most recently in 2014, when 73 Israelis and over 2000 Palestinians died in a summer war that lasted six weeks and saw many residents of Israel’s south— about a third of the country—seek shelter up north.

In Tel Aviv, where the rhythm of beach and life remained essentially unaffected, temporary escapees from the rocket-ridden south were nicknamed “refugees.”

Between last Friday and last Sunday, despite the success of Israel’s Iron Dome anti-missile system, 11 rockets landed within Nahal Oz, a village of some 450 people.

The impact of each rocket hit is similar to that of a bomb, with fire and reverberations. In years past, Yospe, 72, has lost a car to a rocket and, separately, a motorbike, “gone,” he says, whistling, to mimic the sound of a missile flying through the air.

During the war of 2014, Daniel Tragerman, 4 years old, was killed when a shell hit his family’s home in Nahal Oz. The alarm system functioned, but the little boy didn’t make it to the safe room in the required few seconds.

Following the tragedy, the Tragerman family left the kibbutz.

Usually, when sirens wail, Yospe grabs a cigarette and a coffee and passes the time on his porch.

But last weekend was “difficult,” he says, and in part to appease his kids, none of whom live in Nahal Oz, he “took my blankie and went to the safe room.”

According to the kibbutz spokesperson, Yael Lachiani, air raid sirens sounded 42 times during the 50-hours of combat, not taking into account multiple-rocket salvos, which are counted as a single incident.

The fighting ended in a ceasefire brokered by Egypt and the United Nations, and a Qatari pledge to transmit $480 million dollars to United Nations organizations working to help Palestinians, which lost all their American funding after President Trump announced the withdrawal of U.S. aid.

"This is my farher Shalom Yospe

From kibutz nahal oz, in Israels negev by Gaza

This kite was sent as a "present"

Attached to a lit Molotov coktail bottle

In order (to continue) to burn their fields,

If not homes and kindergartens,

Some will call this shocking,

My father, for the last several months,

Calls this reality.

Happy Father's day, dad."

-Adam Raktov Yospe

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has been harshly criticized for embarking on yet another military confrontation, one in which in which four Israeli civilians and 25 Palestinians, including fighters and children, were killed, with no ostensible solution in view.

According to Israeli media reports, the government ordered the army to bring fighting to an end before Israel’s 71st independence day, which was celebrated on Thursday, and the Eurovision Song Contest, a week-long international mega-event starting today which will take place next week in Tel Aviv.

Maj. Gen. (res.) Gershon Hacohen, who commanded Israeli troops on the Egyptian and Syrian borders for 42 years, went so far as to accuse Netanyahu of siding with the Islamist militia in order not to have to engage in any talks with the internationally recognized Palestinian Authority. Last week he remarked that, “Netanyahu's strategy is to prevent the two-state solution, and so he turned Hamas—the Palestinian Authority’s rival—into his closest partner. Outwardly, Hamas is the enemy, covertly it's an ally.”

Yospe is a harsh critic of Netanyahu, complaining that the prime minister “has ruled for 10 years and does nothing with the Gaza Strip, nothing. Bomb and then they go away.”

Israel withdrew its settlements from Gaza in 2005, but, he claims, “we’re still ruling them.” “We’re in charge of water supplies, of electricity, we get the fuel for them, so what can they do?”

A whimsically painted bomb shelter in Nahal Oz

Two million people, he says, locked into a territory of 140 square miles, with no food or water. “All our government says is ‘it's not our problem, the Egyptians will take care of it... But the Egyptians are not taking care of it.”

Netanyahu’s government, he says, reiterating a word used by the prime minister, “see people like us as ‘traitors,’ because we’re on the left of the political map.”

“Who’d want to live in a place like this, where any night you can’t sleep, you have sirens and rockets and the smell of burning rubber, when they light tires during protests, and you’re breathing in the pepper spray which our army uses against them, which the sea wind brings towards us?” Yospe says, describing the questions outsiders ask him.

He admits that he’d be less sanguine “if my children and grandchildren lived here.”

Two of Yospe’s children, a son and a daughter, live in Rockville, Maryland, where his son-in-law owns a booming moving business.

His youngest daughter, Almog, 33, lives in a suburb of Tel Aviv.

His oldest son, Adam, 43, became famous in Israel last year for a social initiative that went viral. Dismayed by the divisions and roughness overtaking Israel’s public sphere, Adam, who lives in the Red Sea resort town of Eilat with his wife and two children, printed up thousands of stickers containing three words meaning, roughly, “Other, you’re a brother,” adorned with a smiling emoji, and began distributing them.

Everyone, it seemed, wanted one.

“I can’t say I am not afraid,” Yospe says. “Anyone who is never afraid is stupid. The question is what you do with your fear.”

He copes well with fear, he says, “so my life is honey.”

His life, it turns out, can be described as one great act of defiance.

A photograph of Nahal Oz residents in the mid 1950s, displayed on one of the kibbutz's original buildings

He was born near Wroclaw, in 1946, when his parents, Jews who survived the Holocaust on the run and had a daughter, Yospe’s sister, in 1944, while hiding in Kazakhstan, “returned to Poland to find the rest of the family, but found no one.”

In January, 1950, the family decamped to Israel, where they initially settled into a transit camp the Israeli government fashioned for new immigrants out of a military base abandoned by the British, who left Mandatory Palestine in 1948.

In his retirement, Yospe has found a second vocation which he fits around travel, his favorite pursuit.

Ten years ago, after surviving a diagnosis of colon cancer that required hospitalization and numerous rounds of chemotherapy, Yospe noticed people turning to him in desperation, to say that a relative enduring cancer had lost the will to live.

Instead of offering advice, he began asking for the patients’ addresses. “I go all over the country,” he says. “I don’t care where. Any cancer patient. I persuade them to live.”