The surprising Islamic beauty of 'Engare'

It all started with a question in Mahdi Bahrami's geometry class.

The first question I ask Mahdi Bahrami is, "How do you say the name of your game?" He laughs and responds smoothly, "Yes, it's called En-gar-ay."

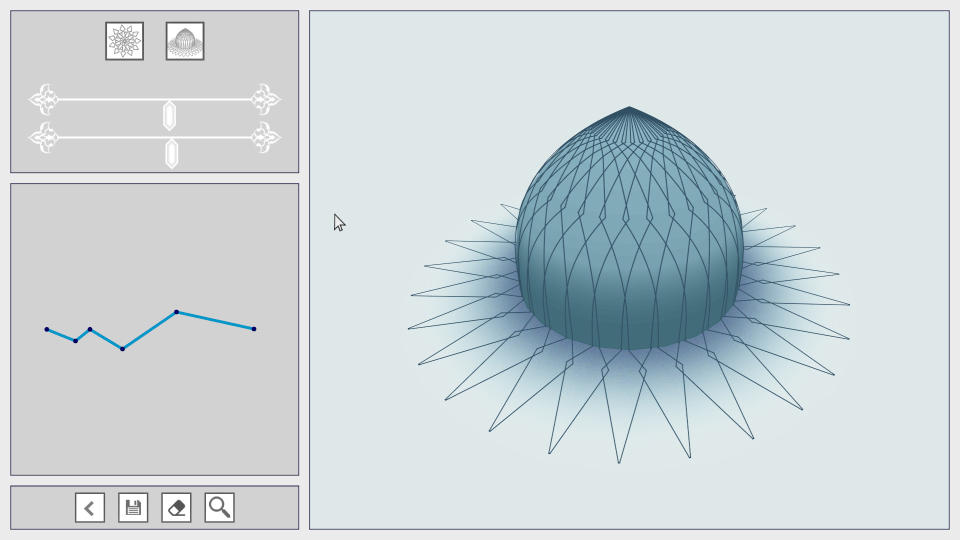

Engare is an eye-catching game. In Steam's sea of gritty multiplayer shooters, pixelated platformers and cartoonish RPGs, it immediately stands out. Engare is sparse yet richly detailed at the same time, filled with looping lines and delicate curves. It's a game about geometry, art and architecture. Put simply, it's a game about beauty.

"When I see these mathematical shapes in a mosque or some other places, I feel like I can see the rules behind it, I can see the mathematics of it," Bahrami says.

Engare's beauty is specific: It showcases Islamic art, featuring sloping arches and densely packed, repeating patterns generated by a geometric approach to design. This is the art of Bahrami's hometown, just outside of Tehran, Iran.

Art in Iran and other largely Islamic countries differs from the Western world's paintings, statues and buildings in a few key ways. The most obvious disparity is a dearth of human portrayals in Islamic art, a phenomenon borne of centuries of religious restrictions.

"In Islam, for so many years, they had this idea that you are not allowed to draw humans," Bahrami says. "It's a sin against God if you draw humans or if you draw living creatures. So all the artists tried to draw everything based on abstract ideas, based on mathematical rules instead of drawing humans. And I'm not saying -- of course everyone should be allowed to draw anything. I don't think that's a good idea to force everyone to draw just abstract ideas. Still, it had some interesting results."

Bahrami studied and worked in Amsterdam for a few years, where he found himself surrounded by Western art and architecture: Gleaming statues of men, women and conquerors lined the streets, and the museums were packed with portraits. It was impossible to miss Western art's focus on the human form.

"Of course the human body is so interesting, there are so many systems in our body, all of these are working and it's fascinating," Bahrami says. "But I don't see all these systems when I see a statue. No, I just see the surface. You don't see what is happening in the head or what is happening in the body, it's all on the surface. On the other hand, when you see something based on mathematical or geometrical ideas, it's more generous. They show you the system of how this was made. That was something interesting for me."

Bahrami is 24, and he's been fascinated with mathematics and drawing since high school, at least. That's where the idea for Engare took root. He was 17, sitting in geometry class, when his teacher proposed a thought experiment: Imagine there's a ball on the ground. Pick one spot on that ball and keep your mind on it as the sphere starts rolling across the floor. "What is the shape that one of the points on this ball would draw while it's moving?" Bahrami asks, remembering his teacher's proposal.

"That question was amazing, and I thought I wanted to make more complicated situations based on this idea," he says.

Engare was born. The game brings Bahrami's mathematical question into the digital world, asking players to envision the designs that would be created by following a single point on a series of rolling, twisting and sliding objects. There's a target image and players attempt to match it by picking a point on a moving object, and seeing what patterns spill forth.

Bahrami built a prototype of his idea that same year and submitted it to the Experimental Gameplay Workshop at the Game Developers Conference in San Francisco. Organizers loved it. Bahrami was in.

The Experimental Gameplay Workshop is an annual space that aims to showcase novel ideas in the gaming industry -- past participants include Katamari Damacy, Portal, Braid, flOw, Mushroom 11 and Thumper. This was 2010, the workshop's ninth appearance at GDC. It was also the only year the Experimental Gameplay Workshop has ever been canceled. There simply weren't enough high-quality submissions, so organizers shut it down and took the year off.

"Later, they told me my project was the only thing that they could show and that was the reason they canceled, they didn't want to show just one game," Bahrami says.

Bahrami kept programming and sending his prototype to the wider gaming world. A few months after GDC fell through, he submitted Engare to Sense of Wonder Night, Tokyo Game Show's version of the Experimental Gameplay Workshop. Curators liked it and invited him out, and Bahrami found himself demonstrating a game in Tokyo before his 18th birthday.

Engare and Bahrami's subsequent projects picked up accolades over the years, including at the Independent Games Festival, IndieCade and even GDC, eventually. It was after one of these conventions that Bahrami read an article about Engare that completely changed the way he thought about his own game.

The story noted Engare's art was distinctly Islamic. Bahrami hadn't actually considered this aspect of his game before, instead focusing on the mathematical allure of its designs.

"And I thought, 'Oh, actually, he's right. It is kind of related to all this art that I have in my city,'" Bahrami says. "And when I was in the Netherlands, I felt more like I really missed those geometrical shapes."

Bahrami embraced the Islamic art style. It's now a central theme in Engare, tying together the worlds of art and mathematics, Middle East and West. It's remarkable that Engare doesn't shy away from its cultural inspiration -- as Bahrami notes, most developers in Iran and across the Middle East attempt to emulate Western games, rather than infusing them with Persian script, towering mosques and other local reference points. The games coming out of these regions are generally white-washed.

The first image on the Engare Steam page is a blue-lined mosque-like building, complete with a pointed dome, a series of archways and delicate details. Engare even includes Persian numbers.

"Everyone's afraid of putting Persian text -- I know developers in Iran who, they make the game in Iran, but they never say it anywhere," Bahrami says. "Nothing. You don't see anything about Iran in the game. Because they are afraid. But, for me, I put Persian text in because the style of the game is kind of like, if I put the numbers in English numbers, it doesn't fit with the game."

Engare wasn't created as a vessel to introduce Islamic art to the Western gaming market, but the thought has absolutely crossed Bahrami's mind. Maybe his game can help translate the beauty of his world to players who generally receive one message about life in the Middle East.

"That was, I think, something that I had in my mind," Bahrami says. "To show these ideas to gamers in Europe, in the US, to show them that the Middle East is not all about killing people. There are interesting ideas, there are interesting types of art here. Because, most of the time, if there's any game about the Middle East, there is someone for sure killing somebody. I don't know good or bad, but it's always about killing."

Locally, the response to Engare has been fantastic. It's been written up by a handful of Iranian outlets and, Bahrami says, people seem to be proud of the game's celebration of Islamic culture. Engare is doing well across the globe, too -- apparently there's a rabid contingent of players in China and the game is selling well enough that Bahrami should be able to pay off investors (Indie Fund helped finance it) and live off subsequent sales for a while.

"It's a lot better than what I was expecting," Bahrami says. "You know, recently, it's really difficult to sell indie games because every day there are a lot of games out there, so it's really difficult to be seen. But at the moment I think it's a lot better than what I was expecting. It got a lot of attention on Twitter and on Steam all the reviews are positive. I think it's going well."

Someone even told Bahrami that they cried while playing Engare.

"The whole game is based on circles and rectangles, there's no story or anything," Bahrami explains. "So, if someone cries -- I didn't expect to make anyone cry with just some rectangles or circles moving on the screen."