Supreme Court fight could stir up fears of US spying overseas

The Supreme Court will hear a digital privacy case this month against Microsoft (MSFT) that could attract international attention and reignite fears that the U.S. government is harnessing tech giants to spy on the rest of the world.

The case, U.S. v. Microsoft, will determine whether the U.S. government can force tech companies to hand over customers’ emails even if they’re stored on foreign servers.

‘Foreign countries may be troubled’

This conflict has captured the attention of Congress, where just this week a group of bipartisan lawmakers introduced legislation that would clarify the rules on cross-border data searches. If that legislation passes, the case against Microsoft may be rendered moot — if not, the Supreme Court will be forced to weigh in on a thorny topic that could pose negative consequences for America’s image abroad.

“Foreign countries may be troubled by the idea that U.S. law enforcement can search the files of any company with a U.S. office, even if those files are located overseas,” says Matthew Tokson, an associate professor at University of Utah’s College of Law and an expert on digital privacy.

“This is especially sensitive territory,” he added, in an email to Yahoo Finance, “because U.S. surveillance of foreigners for national security purposes has already caused foreign countries to be wary of U.S.-based tech companies, hurting U.S. businesses.”

Or, as another associate law professor, Jennifer Daskal of American University’s Washington College of Law, put it, “There’s an ongoing concern about the scope of U.S. surveillance.”

Digital privacy and a 32-year-old law

This dispute involves a 1986 law that many privacy advocates argue desperately needs updating. Under the Stored Communications Act (SCA), law enforcement officers in the U.S. can get probable cause–based warrants to force service providers to hand over so-called stored electronic communications.

In 2013, the government used this then-27-year-old law as justification to obtain a warrant that would have required Microsoft to hand over information for an email account allegedly being used for drug trafficking. However, Microsoft stored the targeted emails overseas, in Ireland, so the tech giant refused to hand them over. In a Supreme Court brief, the company noted that the U.S. “has never suggested that the customer is a citizen or resident of the United States.”

While a district court held Microsoft in contempt for rejecting the government’s request, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit unanimously sided with the tech company on the grounds that the law doesn’t specify that its warrant provisions can be applied overseas. Microsoft noted in a brief that, when Congress passed the law, it could “have scarcely imagined … a world where a technician in Redmond, Washington, could access a customer’s private emails stored clear across the globe.”

Indeed, the SCA was enacted three years before the World Wide Web was born. In the current interconnected world, companies like Microsoft often “migrate” email content and other data to foreign data centers close to users’ reported locations to reduce “network latency,” i.e., delays.

In asking the Supreme Court to reverse the Second Circuit decision, the U.S. government argued that its requests for those emails shouldn’t count as a so-called extraterritorial application of the SCA. That’s because Microsoft would be disclosing the emails in the United States, even though it’s storing them abroad, the U.S. contends.

“[T]he warrant requires disclosure in the United States of information the provider can access domestically with the click of a computer mouse,” according to the government.

The U.S. contends these warrants serve as a valuable tool to prevent terrorist attacks as well as to investigate other serious crimes such as fraud, drug trafficking, sex trafficking and child pornography.

Tech companies step up to protect privacy

Microsoft is not the only tech company to take issue with the government’s contention that it has a right to obtain warrants for overseas data that can be accessed in the U.S.

Last month, some of the nation’s biggest tech companies — including Amazon (AMZN), Facebook (FB), Google (GOOG, GOOGL) and Yahoo Finance parent Verizon (VZ), among others — filed an amicus brief asking the high court to side with Microsoft.

“It’s one of several cases where tech companies are stepping in to protect their users’ privacy,” noted Jonathan Manes, an assistant clinical professor at the University at Buffalo’s School of Law and an expert on the use of emerging technologies in law enforcement and national security. “It’s the tech companies that are sort of holding the government’s feet to the fire with respect to complying with the privacy laws that exist.”

Like Microsoft, these tech companies argued that Congress never could have fathomed today’s interconnected world when it enacted the SCA. And now it’s up to Congress — not the courts — to update that law, they contend. That’s because enforcing these warrants overseas could create a conflict between U.S. interests and those of other countries, according to the tech companies.

The tech companies also raised the possibility that enforcing these warrants overseas might provoke foreign governments to seek data within U.S. borders.

“Every nation founded on democratic principles has a strong and legitimate interest in ensuring that the security and privacy of the people it is charged with protecting are not improperly or unduly invaded,” the tech companies’ brief noted.

That brief added: “Failure to accommodate that legitimate sovereign interest threatens to provoke dangerous reciprocation by foreign governments—at great potential cost to U.S. citizens and service providers.”

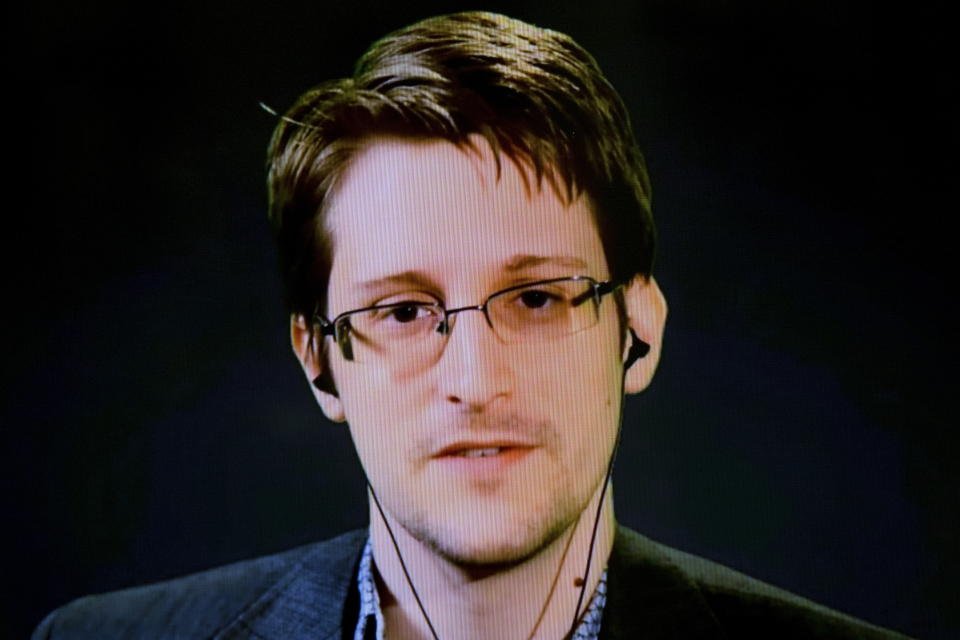

‘A big change following the Snowden disclosures’

American tech giants have become more interested in privacy since Edward Snowden leaked files revealing that U.S. tech companies had facilitated the NSA’s vast surveillance programs back in 2013. The next year, The New York Times reported that the revelations had eroded trust in those tech giants and cost them significant amounts of money. Microsoft, in particular, lost customers, including the government of Brazil.

Manes, the University at Buffalo law professor, noted that he saw “a big change following the Snowden disclosures.” He added, “Their customers were all of the sudden very concerned about privacy.”

In the wake of the revelations, The Times noted, IBM (IBM) spent more than a billion dollars creating overseas data centers to convince customers it was shielding their data from the U.S. government. IBM submitted its own amicus brief in the Microsoft case, noting that it has nearly 60 data centers spread throughout 19 countries, primarily serving enterprise clients rather than individuals.

“IBM … is keenly aware that enterprises are sensitive to government overreach, particularly in the wake of disclosures relating to the U.S. government’s foreign intelligence surveillance programs,” the IBM brief noted.

An uphill battle for Microsoft

Despite the support from IBM and the other U.S. tech companies, Microsoft may be gearing up for an uphill battle when the high court hears the case on Tuesday, Feb. 27. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit already sided with Microsoft in this case, and there are currently no other appeals courts that have issued contradictory opinions.

When appeals courts issue opinions that contradict each other, it’s known as a circuit split. Since there’s no split in the Microsoft case, it’s likely that the four justices who voted to take on the case did so because they’re interested in overturning the Second Circuit decision and handing the U.S. government a victory.

“The court will likely be reluctant to hinder US law enforcement, especially in cases where law enforcement secures a valid search warrant,” noted Tokson, the University of Utah law professor. Still, he added, “This is a very difficult case and I’d expect a divided court and a close decision either way.”

A Congressional fix?

The Clarifying Lawful Overseas Use of Data Act, or Cloud Act, introduced in Congress this week, would clarify that U.S. warrants for data apply worldwide. But it would also let tech companies notify foreign governments when they receive requests for such data from the U.S. government. That way, those foreign governments can intervene if they deem requests to be inappropriate, according to a statement from the bill’s sponsors.

Ideally, Congress would quickly enact the Cloud Act, according to Daskal, the American University professor, who received an Open Society Institute Fellowship to work on issues tied to cross-border data requests. She noted that, remarkably, both the DOJ and Microsoft support the legislation. (The media division of Yahoo parent Verizon, Oath Inc., has also supported the legislation.)

That legislation “recognizes that access to data should not depend on location of data, but also takes steps to respect the legitimate foreign government interests in delimiting access to their own citizens’ and residents’ data,” Daskal noted in an email message.

If Congress doesn’t act, the Supreme Court may rule for the government but also direct courts to engage in a so-called comity analysis if the warrant seeks data of a foreigner outside the U.S. and creates a conflict between laws, she noted.

“Such a decision would require the U.S. government to consider other countries’ interests when seeking electronic data of their residents and citizens much as the United States does and should demand when foreign governments seek U.S. citizen data,” Daskal noted in her email.

However, if the high court gives the U.S. government carte blanche to demand foreigners’ data from U.S. tech companies across borders, the privacy rights of U.S. citizens may be in peril, Microsoft noted in its brief.

“If this Court declares that unilaterally seizing private correspondence across borders is a purely domestic act, then the United States will have no basis to object when other countries reciprocate and unilaterally demand the emails of U.S. citizens stored in the United States from providers’ offices abroad,” the Microsoft brief noted. “If we can do it to them, they can do it to us.”

Erin Fuchs is deputy managing editor at Yahoo Finance.

Read more:

Why the ‘gay wedding cake’ Supreme Court case is really about corporate governance

Supreme Court may overturn decades of precedent in cellphone privacy case