Supreme Court Agrees To Hear Controversial Gun Case That Could Allow Abusers To Possess Guns

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The Supreme Court agreed Friday to settle the question of whether domestic abusers subject to protective orders can possess guns, when it agreed to review United States v. Zackey Rahimi — a hugely controversial case that may help clarify widespread confusion over how to interpret the court’s bombshell Second Amendment ruling from last year.

The court issued a new standard for judging the constitutionality of gun laws in last year’s Bruen v. New York State Rifle and Pistol Association, which overturned a New York law dating back to 1911 that barred people from carrying a handgun without a license. Under that law, New York could deny a license to applicants who failed to prove they faced a specific threat.

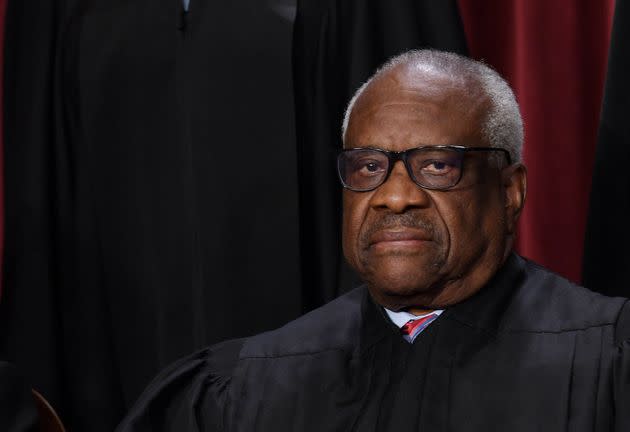

Associate Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas poses for the official photo at the Supreme Court in Washington, D.C., on Oct. 7, 2022.

The ruling written by Justice Clarence Thomas and supported by the court’s five other conservatives said the law infringed on the right to bear arms. The decision also trashed the old standard of balancing interests like public safety against an individual’s Second Amendment rights, instead dictating that firearm restrictions are constitutional only when they’re “consistent with this Nation’s historical tradition of firearm regulation.”

The new historical standard of gun law constitutionality appears to lie somewhere between 1791, when the Second Amendment was adopted, and some unspecified point in the 19th century.

In the wake of Bruen, federal courts across the country have thrown major gun laws into question. State-level bans on assault weapons or “ghost” guns, the age limit for buying a handgun and restrictions on gun possession while under felony indictment have all been overturned by lower courts or reviewed at the request of the Supreme Court.

Rahimi was arrested in early 2021 in connection with a handful of shootings over a two-month period in Arlington, Texas. He allegedly shot several times into someone’s home after selling that person drugs, according to court filings. He allegedly shot at another driver after the two had a car accident, drove off, then came back in a different car to shoot at the other driver again. He is accused of shooting at a constable’s vehicle, then firing a gun several times in the air a couple of weeks later at a Whataburger, after a friend’s credit card was declined.

When police searched Rahimi’s home, they found a pistol and a rifle ― both violations of the terms of a protective order he received for alleged violence against his girlfriend. Federal prosecutors convicted him for possessing firearms while under a protective order.

But Rahimi, represented by federal public defenders, appealed the conviction. When a panel of three justices reviewed the case after the Bruen decision, they looked for the historical analogy that the Supreme Court now demands to uphold the constitutionality of gun restrictions, and didn’t find one. Two of the three justices were appointed by Trump.

Calling the federal law an “outlier that our ancestors would have never accepted,” the Fifth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals overturned Rahimi’s conviction and restored his gun rights. (Rahimi remains in jail while his state-level criminal cases move forward.)

The decision upholding the gun rights of someone facing serious allegations of domestic abuse and repeated criminal misuse of firearms shocked gun reformers and advocates for victims of domestic violence. If stripping the gun rights of domestic abusers were to become unconstitutional, it’s hard to imagine what restrictions might pass constitutional muster under the new standard.

Many observers view the Bruen decision as far too broad and vague, and have expected that future rulings will clarify what they meant.

A decision in the Rahimi case is not likely until next year.