He was a superstar ball player in Texas. You’ve never heard of him because he was Black

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Our Uniquely Fort Worth stories celebrate what we love most about Cowtown, its history & culture. Story suggestion? Editors@star-telegram.com.

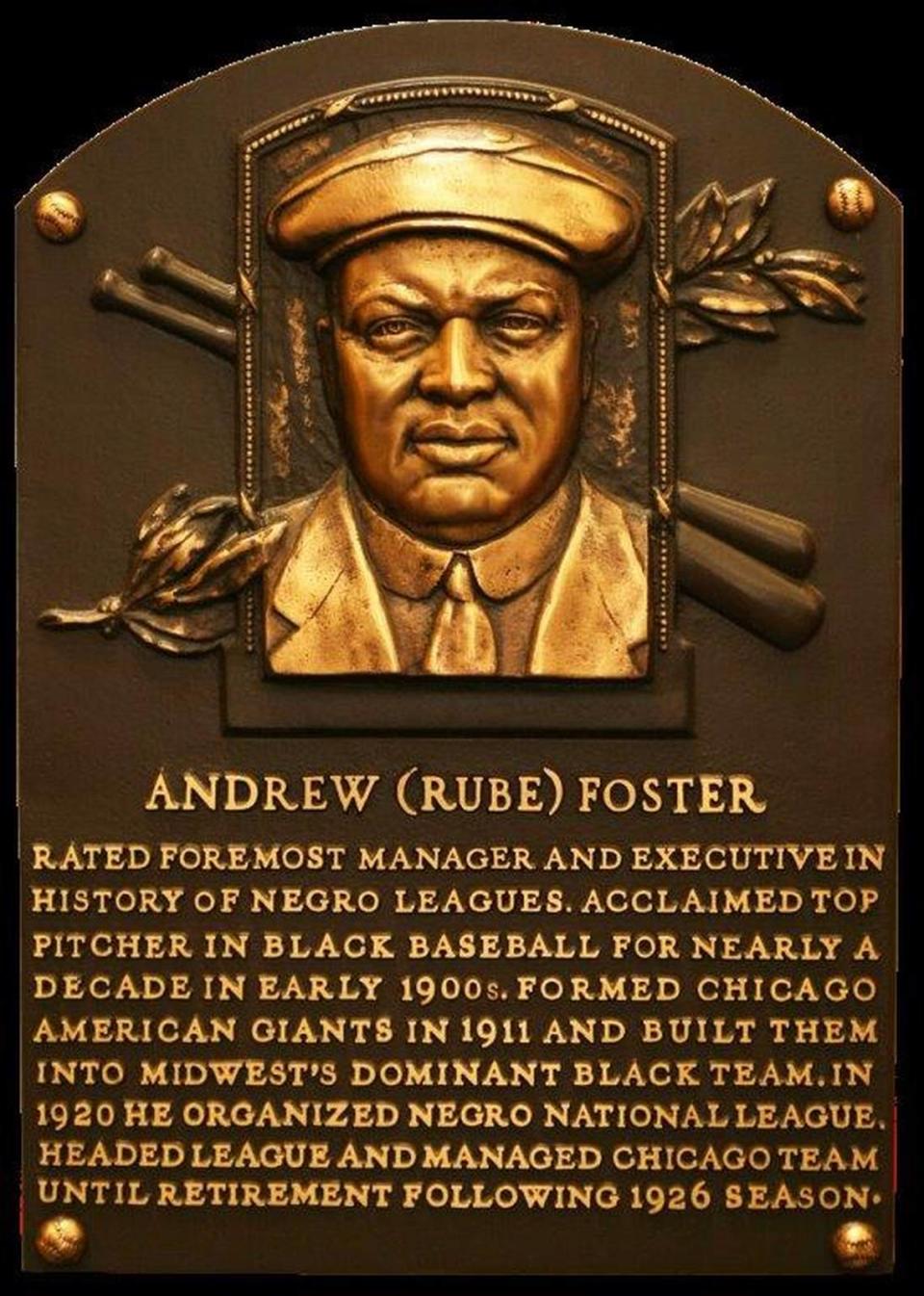

Andrew “Rube” Foster is known as “the Father of Black Baseball.” He is in the National Baseball Hall of Fame, has a Texas Historic Marker at his birthplace, and has been honored with both a U.S. postage stamp and U.S. Mint commemorative coin.

Now, he is being honored in a joint effort by the New Mount Rose Missionary Baptist Church, Fort Worth Parks & Recreation, and the Texas Rangers baseball team with “The Black on Base Negro League Presents: From Cowtown to Cooperstown, Andrew Rube Foster,” which will climax with a “Rube Foster Hit, Pitch & Run” event for kids at Gateway Park on April 20.

Though there has already been a lot written and said about Foster, little of it covers his years playing semi-pro ball in Texas when he became a Lone Star legend as a pitcher. If he had been white, he would have been in the major leagues as a teenager. But he was Black, so his exploits were only reported below the fold on the back pages of the newspapers, if at all.

He was born in Calvert, Texas, on Sept. 17, 1879. Attending a segregated school, Foster got as far as the eighth grade before dropping out to pursue his athletic talents. This was before the days of organized Black basketball and football, so a big, athletically talented Black man headed to the baseball diamond. Foster reportedly had a killer fastball and screwball that gave batters fits.

He also lacked the advantage of throwing off a pitcher’s mound. That came later. The field in his day was flat. Pitchers pitched off a “rubber.”

A star with the Waco Yellow Jackets

As a 16-year-old, he joined the Waco Yellow Jackets, a barnstorming team that played all comers. The kid from Calvert was an immediate sensation, pitching the Yellow Jackets to unprecedented success in the next four years, in the process earning the descriptive “famous” in front of the team’s name. Waco adored them, and attendance wasn’t hurt by the fact that games involving Black baseball teams had free admission by Waco ordinance. The club set aside a section of the bleachers for white fans who came out to see the pitcher nobody could touch.

On July 18, 1899, they played the Fort Worth Wonders, who had lured away seven former Yellow Jackets. Foster was in the “pitcher’s box” at home for the first time that season. When he took his place, the crowd at Golden Gate Park burst into cheers of “Hurrah for Foster!”

They knew what was coming. In the next nine innings, he struck out 17, allowing only two base hits. He walked off the field at the end of the game to more cheers. Perhaps most remarkable, this was his 22nd game in a season that was only three months old, and he had pitched 12 straight games without giving up a base hit. The Waco newspaper, with understandable pride, called him, “the best ball player and pitcher in the South” without making the usual distinction between Black and white players.

Before the 1901 season, the man known as the “Texas Star” traded in his Yellow Jackets uniform for a Fort Worth Colts uniform. How the Colts managed to steal him from the Yellow Jackets is a mystery, but it probably had a lot to do with offering more money and a bigger fan base than Waco.

The Colts went through the 1901 season like a buzzsaw, losing only one game. At the end of June, manager Will Snow issued a public challenge to manager W.J. Tackabery of the Fort Worth Cannon Balls for “any wager he can afford.” The bet: that Foster would strike out no fewer than 18 men. The Cannon Balls weren’t just any team; they were the highly regarded, white ball club of the Texas & Pacific Railroad. There is no record whether Tackabery took up the challenge.

The Colts were back in Fort Worth on Aug. 4 for a two-game series against the Yellow Jackets in Texas & Pacific Park. This was the first time the teams had faced off since Foster pitched for Waco. The Fort Worth newspaper called the Waco club “a good team of ball players,” admitting that the last time the two teams played, the “famous” Yellow Jackets took three straight games from the home team. Fans were encouraged to come out and see the Texas Star thrash his former team. Foster pitched the first game, won by the Colts 8 to 3.

The Colts played the Yellow Jackets for the last time in the 1901 season on Aug. 29. They played in Waco, but homefield advantage did not help the Waco team with Foster in the box. Even the local newspaper had to admit that the man who was “formerly one of the Yellow Jackets” was so dominant the hometown team “could not do a thing but stand and take it.” With the final score 19 to 1, the reporter pronounced it “a thorough defeat” which could have been worse, but the Fort Worth team was feeling “generous.”

The Colts barnstormed across the South and Midwest in 1901, playing teams in Kansas City, Missouri; Hot Springs, Arkansas; and Chicago. Everywhere they went the results on the field were the same: they won. Their stop in Chicago was especially important because the next year the Chicago Union Giants came calling on Foster.

Foster only played two seasons in Fort Worth. By his second season, the hometown teams was being called “the famous Colts,” while the formerly “famous” Yellow Jackets, without the Texas Star pitching for them, had fallen back into the pack.

In 1902, Colts ownership placed sporting bets with opposing team owners. When in April they played a Dallas team that boasted an ace they got from Little Rock, there was a $400 “purse” at stake. The Colts won.

The crowds at Foster’s games now included scouts as well as fans. Word had gotten around the baseball world about the Texas wunderkind, and the Chicago Union Giants wooed him away from Fort Worth with the usual inducements. Relocated to Chicago, he was still playing in the Negro Leagues, but on a bigger stage. In the years that followed, he continued to bounce from team to team, following the money. He played for Chicago, New York, and Philadelphia. In every city the crowds came out to see him pitch.

Foster gets the nickname of ‘Rube’

Foster was not known as Rube Foster in Fort Worth. He got the nickname when he out-dueled white star pitcher G.E. “Rube” Waddell in an exhibition game in Philadelphia. Thereafter he was known as the Black “Rube” and eventually just “Rube.”

Foster eventually did everything, both taking the field and managing teams, including a hand-picked bunch of traveling all-stars, the Chicago American Giants. In 1920, Foster and seven other owner-managers of Black clubs formed the Negro National League. The high regard they held Foster in was indicated by the fact that they elected him as their first president and treasurer. His club won the pennant three successive seasons before he suffered a nervous breakdown that forced him to retire. Four years later he died on Dec. 10, 1930. Sports writers all over the country lamented his passing and celebrated his accomplishments. Thousands of fans, both Black and white, turned out for his funeral in Chicago.

Fort Worth’s Black superstar was only a memory by then, but his legacy lasted beyond the two seasons he played here. Foster’s old Fort Worth team changed its name from the Colts back to The Wonders (sometimes with “World” in front of it) and continued their success, winning 15 of 17 games to begin the 1907 season. They routinely attracted crowds of 1,000 or more fans for home games. Success allowed them to move from the decrepit Texas & Pacific Park to Douglass Park four blocks north of the Trinity River (named for civil rights icon Frederick Douglass).

Management of the team passed to prominent saloon man and Republican stalwart Hiram McGar, who had the money to enlarge the grandstands of what became known as McGar Park. He still reserved a section for white fans because since Foster’s time they had come out regularly to see the team play.

One of the intriguing questions about Rube Foster is whether he ever faced any white major leaguers while pitching for the Colts. It is known that the Cincinnati Reds brought their team to Fort Worth and Dallas for spring training in the early 1900s. They squared off against the local teams in both cities to prepare for the coming season, but there is no record they ever played the Colts.

It is long past time for Fort Worth to honor its first superstar ball player, Black or white, in any sport. No other athlete was referred to as the “Texas Star” before Andrew Foster, and even before he became the Father of Black Baseball in the nation, Rube Foster was the man who brought white fans out in droves to see Black baseball in Texas. It is telling that before Foster, Fort Worth’s white newspapers rarely, if ever, covered Black teams. After he arrived in town in 1901, the Colts and their successors were regularly covered. Fort Worth can rightfully claim a piece of Andrew “Rube” Foster history just as we claim a piece of the world champion Texas Rangers. Not too shabby!

Sign up for the “Rube Foster Hit, Pitch & Run” event at https://bit.ly/497cwV9.

Author-historian Richard Selcer is a Fort Worth native and proud graduate of Paschal High and TCU.