Sunken Vases Double As 2,000-Year-Old Biology Experiments

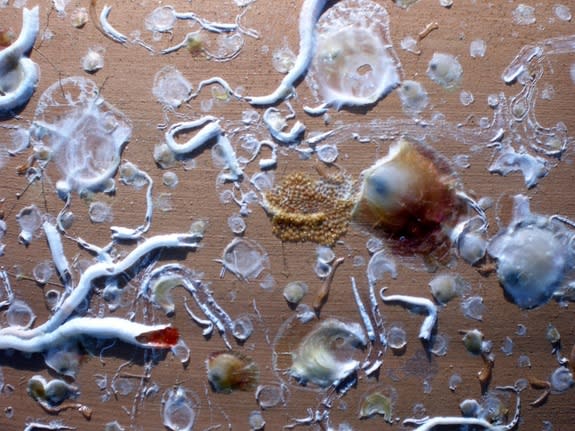

CHICAGO — Oysters, barnacles and corals that cling to ancient artifacts strewn about the seafloor are often a scourge in the eyes of marine archaeologists; researchers might spend days carefully scraping stubborn life forms off vases pulled from shipwreck sites. But some scientists say these nuisances deserve more attention.

The RPM Nautical Foundation is starting to document the creatures clung to ancient ceramic amphoras, as they map shipwrecks throughout the Mediterranean. These new data points promise to help scientists learn more about the region's underwater ecology and history, Derek Smith, a researcher at the University of Washington and RPM team member, explained here Friday (Jan. 3) at the Archaeological Institute of America's annual meeting.

To study how species spread and colonize in different underwater regions, ecologists traditionally lay down small square tiles and return to them in a year or so to see what's latched on, but amphoras are actually a much better proxy for the natural environment, Smith said. [See Underwater Photos of the Life Thriving on Ancient Vases]

"The amphoras have shape to them, they've got little cracks and crevices, they've got an interior and an exterior space, they've got different material types like different clays from around the region — things like that inspire all different communities to show up," Smith told LiveScience. "So looking at things that have been in the ocean for 2,000 years versus one year on a settlement tile provides clues to settlement and recruitment processes that you can't get anywhere else in ecology."

An understanding of the creatures that take up residence on undersea artifacts can also help archaeologists combat bioerrosion and refine their conservation efforts, Smith said.

"As an ecologist, I can go down there and say, 'These three types of sponges are boring into your amphoras. If you're going to pull anything from the site, pull these three first,'" Smith told LiveScience.

And looking at the telltale traces of different organisms on underwater artifacts can give archaeologists clues about whether their finds are still in situ or have been moved over the years. For example, Mediterranean sediments become anoxic, or devoid of oxygen, in about the first centimeter or two below the sediment surface, Smith said. That means the buried side of amphora might turn black because of growth from anoxic bacteria, so if that black side is facing up when found, archaeologists know it must have been turned over at some point.

Understanding how these shipwrecked artifacts have moved over time could provide new insights into the impact of human activities like trawling, which can drag these vases across the bottom of the ocean, Smith explained. And knowing which materials attract certain species can also help researchers figure out the best ways to build artificial reefs.

Smith's work is part of a larger interdisciplinary effort called the Organization for Mediterranean Archaeology, Geology and Ecology, or OMEGA, which is trying to bring information on bathymetry, shipwrecks, artifacts, species distribution and video footage into one huge searchable database.

Follow Megan Gannon on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Copyright 2014 LiveScience, a TechMediaNetwork company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.