Students fell behind during the pandemic. How 1 educator is closing the learning gap

In 2020, as classrooms across the country shifted to remote and hybrid learning, millions of students nationwide fell behind academically. By the fall of 2021, almost all students were back in school full-time, according to the National Center for Education Statistics. Still, closing the COVID gap is taking time.

According to NWEA, by the end of the 2023 school year, the average student needed 4.1 more months to catch up in reading and 4.5 more months in math. Students in high-poverty school districts lost more ground than others, reports the Harvard Graduate School of Education.

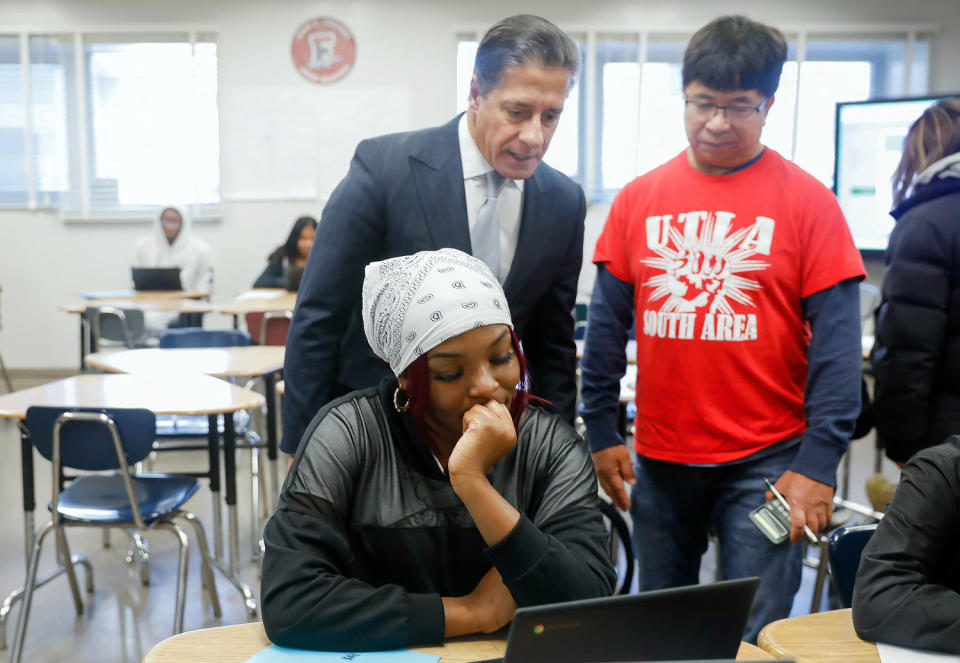

Alberto Carvalho is looking to change that for the more than 420,000 students in the Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD), where he came on board as superintendent in 2022.

According to reporting from the New York Times, Los Angeles, the second-biggest public school district in the US, had less learning loss than many other big city districts and has had a better recovery rate than other districts in California.

Here are some of the strategies Carvalho and his team have put in place that are making a difference.

1. Getting kids into the classroom

The challenge: Kids can’t learn if they aren’t in class. Nationwide, chronic absenteeism — kids missing at least 10% of a school year — was 75% higher in 2023 than before the pandemic, according to the American Enterprise Institute.

It’s not just a problem for the kids who miss school — when kids aren’t in school consistently, it disrupts the classroom flow for everyone.

The strategy: Tech-based solutions weren’t getting solid results. “We have platforms that can conduct virtual outreach to parents and students, but that was falling a bit short of the mark,” Carvalho tells TODAY. Instead, the district is using an old-fashioned method — knocking on doors.

A team that can include a counselor, social worker and principal or assistant principal meets with an absent child’s caretakers. The team has data about the student, so they can connect with the caretaker. “We are meeting students and parents where they are, and we’re bringing solutions after really understanding the root cause behind the chronic absenteeism,” Carvalho says.

The outcome: The district is back to its pre-pandemic average daily attendance levels of 92 to 93%.

Still, there’s room for improvement. “With every knock on the door, we learn new circumstances or reasons [for absenteeism],” Carvalho says. For example, parents worry about immigration consequences, or older kids stay home with babies and toddlers while their parents work two or three jobs.

For those issues, the district needs help. “Solving for that requires a new adaptation to a host of social services and supports that transcend the school system,” he says. “It requires the city, the county and community-based organizations to step in and step up.”

2. Looking beyond the limits of the school calendar

The challenge: Schools need to create opportunities for learning outside of the 7.5-hour, 180-day traditional classroom schedule.

The strategy: The district helps kids close their gaps by offering outside-the-school-day options like:

Before- and after-school programming

Tutoring

Saturday, spring break and winter break academies

A summer of learning

Speaking more broadly about these types of changes, Carvalho says, “This is in part the response to the crisis that started with the pandemic, but honestly, this is a response to the failures of many systems for many decades prior to the pandemic. Returning our students back to pre-pandemic status is insufficient. We have a golden opportunity to really transform educational systems as we know them.”

Carvalho recognizes that you can’t simply saturate kids with core subject instruction, though: “If all you do is provide them with more reading and more math, you’re probably going to reach a level of fatigue that will disengage them.”

Along with core subjects, his district is bringing in a portfolio of enrichment activities in the arts, including field trips to plays and concerts. They’re inviting artists to schools. “It’s how you package it,” he says.

The outcome: More than 30% of the student body has participated in summer programs, and other programs are showing solid participation as well. Carvalho says that so far, data is showing significant improvements in state assessments. And the district is posting its highest graduation rates in its history.

3. Closing the gaps for underserved students

The challenge: The students in the 100 lowest-performing schools in the LAUSD are disproportionately Black and brown. These schools have huge numbers of students who have disabilities, are English language learners, are experiencing homelessness or are in the foster care system.

The strategy: The district is using data to build equitable support and accountability. “Data is our superpower in Los Angeles Unified,” Carvalho says. They adjust funding based on each school’s demographics. They are also building strategies that improve the performance of subgroups of students. For example, they’ve allocated $120 million toward the Black Student Achievement Plan (BSAP).

The outcome: The BSAP is still ongoing, and it’s showing solid gains in improving attendance, math and literacy, and students enrolled in advanced placement or honors classes.

4. Connecting parents with their power

The challenge: Parents and communities have often historically sent their kids to school and expected them to behave. After that, they viewed education as the job of the schools and the teachers. Carvalho wants to change that.

“I want to show parents how they can become powerful voices of disruption in their own schools by empowering them with information,” he says. That way, they know the important questions to ask teachers, principals, superintendents and board members.

The strategy: The district launched Family Academy, a virtual platform for parents, two years ago. It gives parents a better understanding of their children’s education and performance and shows them how to be change agents in the classroom and the school.

The outcome: Thousands of parents have gone through training programs. They understand budgets and proficiency levels. “Once parents understand that, they can become more active voices,” Carvalho says.

5. Recognizing that closing gaps will always be a focus

The challenge: “I don’t think we will ever close the gaps,” Carvalho says. “The reason for that is that our school systems have wide-open doors. As much as we can improve the conditions for learning and performance of the students we have today, each and every day, we bring in new students.”

Babies are born already falling into gaps. Some immigrant students are dealing with language barriers, trauma from warfare or from a treacherous journey to the U.S.

“One of the things that frustrates me as an educator of many years in this country is that all of a sudden, the nation woke up to the fact that there were gaps, and a lot of people assigned the gaps 100% to the pandemic,” Carvalho said. “Gaps have existed. The systems of education as we know them have perpetuated gaps.”

The solution: Parents got a front-row seat to their kids’ educational environment during the pandemic, and they aren’t going back to the old way of doing things. Transparency helps. The district publicly shares data on everything from kindergarten literacy benchmarks to trends in graduation rates through its open data portal.

The outcome: Carvalho references a famous quote from Maya Angelo: “‘When you know better, do better.’ That’s where we are right now.”

This article was originally published on TODAY.com