Struggle for affordable child care persists in Delaware. That's for parents and providers

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Trace a radius, fill the spreadsheet.

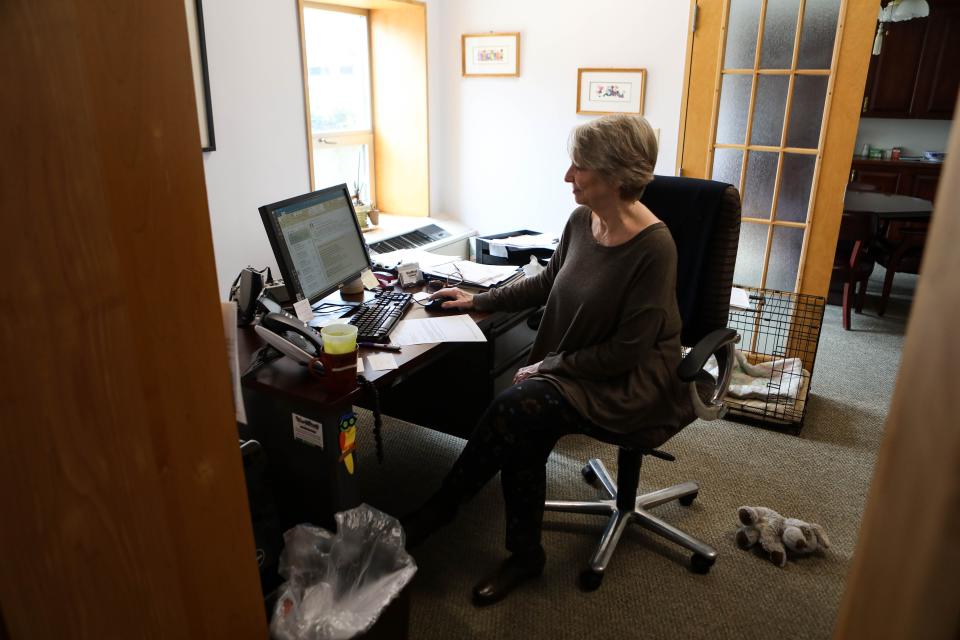

Amy Wasserman figured she would tackle her child-care search as she does work: Organize the data. Their baby girl was just a few months old when she and her husband moved back to Delaware in late 2019, zeroing a search for childhood centers around their Wilmington-area home.

Perched at the computer, they watched rows and columns grow with price quotes and waitlists, time estimates and reminders, who to call and who to call again. Several pushed out of price range, while others didn’t have room anyway.

“It was like, do they have availability? Yes, No. If no, what's the waitlist look like? When would they have availability? When would we know? How far is the distance?” Wasserman recalled. “It's just, it's crazy.”

The couple found a spot by January 2020, just in time for pandemic shutdown to send them back home. Then, they started over. They found early childhood care they could trust for their just-over-1-year-old by 2021.

Only, it comes nearly equal to the monthly payment on their mortgage.

Middle-income families are struggling to afford child care in Delaware, while providers themselves cite continued burnout, staffing shortages and their own struggle to provide it.

Some 44% of families said they can't find a program with room, can't find a program that fits their schedules or simply cannot afford it, according to a 2023 survey released by Rodel Foundation and a coalition of partners. Providers and advocates alike are asking Delaware to lower the guardrails, supporting them to help more families access subsidized child care.

The state has found ways to respond.

In the draft budget for next year, Purchase of Care — with $83 million dog-eared for the child-care subsidy — would see family eligibility expanded to 200% of the federal poverty level, up from 185%. According to the state, this would expand access to subsidized care to over 600 more children.

A $3.5 million increase for Delaware's Early Childhood Assistance Program, or state-funded pre-K, would also add at least 200 seats for early care and education. This proposed budget would mark more than doubled investments in both buckets since 2017 figures, while last year came with its own renewed investments.

Some say these increases in a complicated system just aren’t keeping up.

“How can we stop nickel-and-diming this industry?” posed Sen. Laura Sturgeon, in a budget hearing late last month. “Isn't that really what will move the needle in terms of helping to bolster this industry that is much needed — and in a bit of crisis?”

Package: Meet Delaware's Most Influential People 2024 in education

'We're just spinning wheels’

Toni Dickerson remembers jumping on a statewide call with Delaware providers earlier this year. She logged on from her office with Sussex County Preschools, finding a break in another draining day.

But there, she’d be met with tears, yelling and frustration radiating between Zoom tiles.

“There are programs that don't know how they're going to make it to the end of 2024,” said the administrator back in January. “We're all exhausted. All of us leaders went through the pandemic and there was enough going on in that in those couple of years — but that same level of exhaustion is still here because we're just spinning wheels.”

There’s been talk of strikes. Leaders feel they're working as teachers, as family social workers, as budget acrobats. Staffing ratios are balancing acts, profit margins gaunt.

Dickerson relies on state programs to keep four program doors open for about 300 kids, as she estimated roughly 90% of her families receive state subsidies. That figure wasn't uncommon. She still has families helping with filing systems, another with housekeeping, in lieu of child-care tuition or copays.

In the heart of Wilmington, Lucinda Ross said St. Michael’s has always looked after the city's most vulnerable. And it's getting harder.

Some providers caring for the most high-poverty areas in the state say some recent increases in funding have been lost in agency reshuffling. Purchase of Care funds were boosted in 2023, while the Redding Consortium was folded into the new state-funded pre-K. For some, it resulted in their overall state reimbursements declining from promised rates.

“It’s a shame, because what would look like two and three steps forward, for many of us on the provider side, it's like three steps backward,” said Ross, executive director of St. Michael’s School and Nursery.

Regardless, impact for providers also changes by ZIP code.

Providers like Dickerson in Sussex and Kent counties still receive around 27% less in Purchase of Care funding per-child than New Castle County neighbors, per Rodel projections. That’s based on a market-rate survey providers say hasn’t been updated in about 30 years.

"It's defeating," said Brittany Zimmermann, director of another center in Millsboro. "I have a bachelor's degree, halfway through finishing my master's... I just wish that early education was viewed as important as K through 12."

This year, Department of Health and Social Services told the Joint Finance Committee that two surveys are underway — the typical market rate, now joined by a new cost-focused study.

It meets concerns of low pay plaguing workers in the industry, struggling to attract the best possible employees. Early childhood providers are not state employees, like teachers, whose salaries are rising by legislative effort.

"We have to bring the cost down for the people who use child care, but we have to make sure we're paying the workforce more," Sturgeon (D-West Brandywine Hundred) told Delaware Online/The News Journal. "And doing both of those things obviously means there has to be government investment into this industry."

Next read: 'We cannot normalize failure': Wilmington Learning Collaborative eyes lofty goals ahead

Families struggle, by the numbers

Child-care costs are already some 10% of a married couple’s median annual income per child, on average, per Rodel research. That's on par with housing costs for many, or some in-state university tuition.

In Delaware now, a family of four must earn less than $55,000 to be eligible for publicly funded child care, according to the same research. That cutoff will likely rise to about $60,000 by next fiscal year, if the current proposal of 200% of federal poverty level holds.

Pennsylvania, New Jersey and Maryland offer such assistance to families earning up to 250 or 300% — while some states reach 575%.

“But someone smarter than I crunched the numbers and found that this would exclude a family where each parent only makes minimum wage,” said Sturgeon, back in the same budget hearing. “Two parents making minimum wage would not qualify for the subsidized child care — and that just seems like we aren’t doing enough.”

During the hearing, many speakers and lawmakers alike returned to 250%.

DHSS leaders said they don’t believe there’s enough data yet on demand at that percentage, but more fiscal study could be done.

The department must prepare to weather other costs that stand to impact families. Copays will soon be rolled back, department leaders told lawmakers. What’s now up to 9% of a family’s income, may be 7%, while the most vulnerable families will likely no longer face fees.

Many providers said a thorough review of the system is long overdue.

Some lawmakers agree, in so many words.

Highlighting paraprofessionals: These roles are growing like never before in Delaware schools. And they aren’t the teachers

Hopes for change continue

The system of early childhood education can get complicated. The sector has come up in a few budget hearings.

Purchase of Care is seen as a workforce development program, under Delaware’s Department of Health and Social Services, while Delaware's Early Childhood Assistance Program, or State Funded pre-K, falls under the state’s Department of Education.

In the latter hearing, Redding Consortium says the bulk of its $10.2 million in funding will go to wraparound services and state-funded, full-day pre-K. Increases for both state programs have remained unchanged in the draft spending plan, as of yet.

Sturgeon, for one, hopes to resurface these issues by final budget markup, if forecasts allow.

If there's a rosier next forecast for state revenue, "Then we could take the monies that are forecast to come in and apply them where we need most," the senator said. "And I would say child care is at the top of that list."

Some lawmakers seemingly expressed hesitation.

“This committee has made double-digit increases over the last five years,” said state Sen. Trey Paradee, JFC chairman, of state programs during another hearing. The Democrat noted that subsidized providers “come in all different sizes, shapes, flavors and colors,” from home care to early childhood centers.

He said many providers are clearly doing great work, providing early education, allowing kids to get a jump on reading comprehension. “My fear, is that you have some providers that are simply plopping kids in front of the television and are really nothing more than glorified babysitting,” he said. Paradee (D-Dover) nodded to both possible standardized curriculum and collecting better data.

All committee members agreed safety needs to be prioritized. And Paradee said future lawmakers should be able to see “what’s really working” after this body makes decisions.

But from advocates to providers, to guardians and parents like Amy Wasserman, something certainly doesn’t feel like it’s working.

“People just aren't aware,” Wasserman said, having also spoken at JFC.

The mom remembers a young woman joking with her recently, saying providers must be rolling in profits given how expensive child care seems today.

“And I was like: ‘Actually, they're not. They're really, really struggling. They can't pay their employees, they can't staff,’” she continued. “I think there's this misunderstanding in the public, unless you're in it, that yes, we're paying a lot for child care — but it's because it costs a lot to take care of a child. And the people that are doing this work really aren't being paid.”

Education roundup: High school, state programs honored as 'Superstars' in Delaware

Got a story? Kelly Powers covers race, culture and equity for Delaware Online/The News Journal and USA TODAY Network Northeast, with a focus on education. Contact her at kepowers@gannett.com or (231) 622-2191, and follow her on Twitter @kpowers01.

This article originally appeared on Delaware News Journal: Delaware child care: Families strain to afford it, so do providers