Strike 3, he's out: How former Vanderbilt pitcher Jeff Edwards fell just shy of MLB 3 times

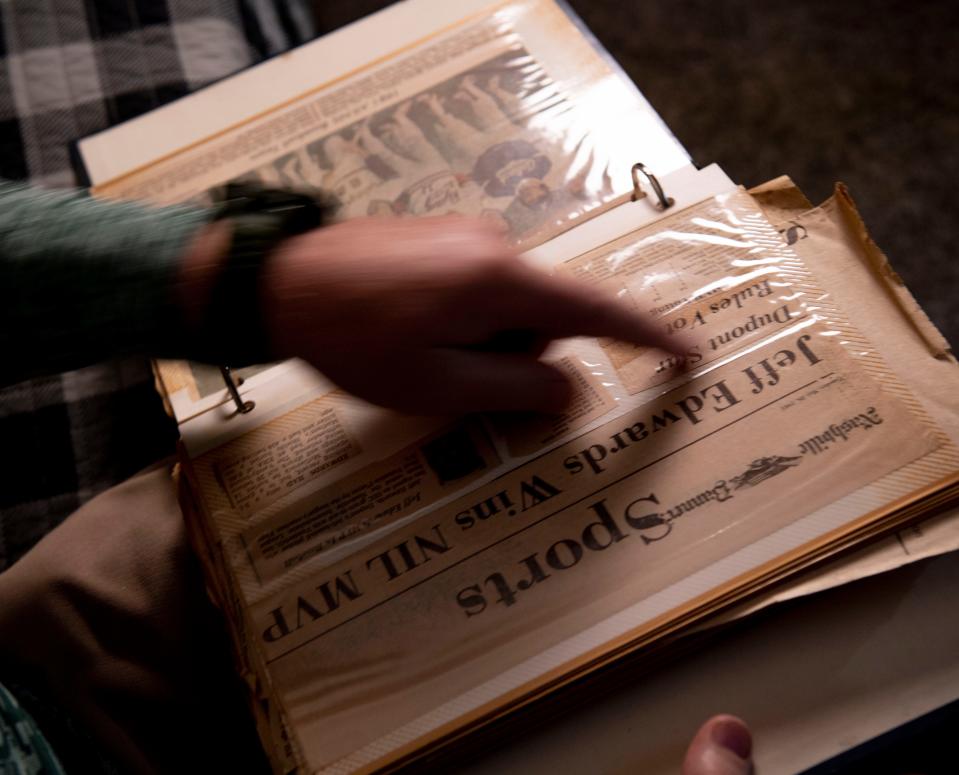

For most of the past 30 years, what-could-have-beens and what-should-have-beens rested mostly undisturbed in a dark blue three-ring binder.

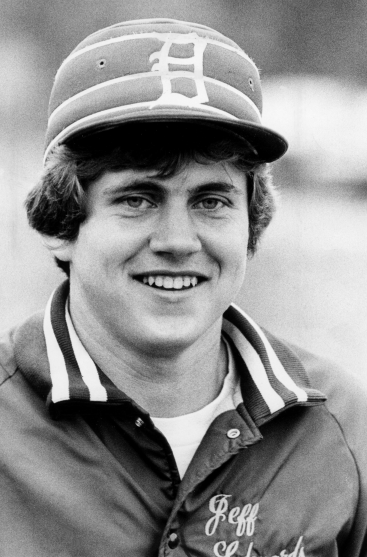

Spelled out on the front of that 114-page keepsake with the spine partially torn from the top is the name — JEFF EDWARDS — painted in giant white capital letters. The name belongs to a former DuPont High and Vanderbilt left-handed pitcher who three times came this close to making it to the major leagues.

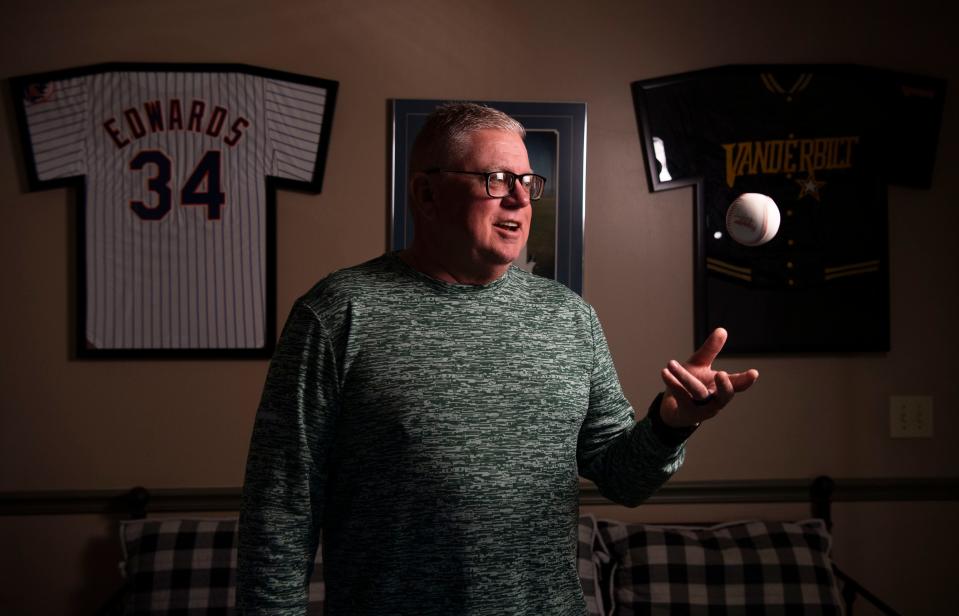

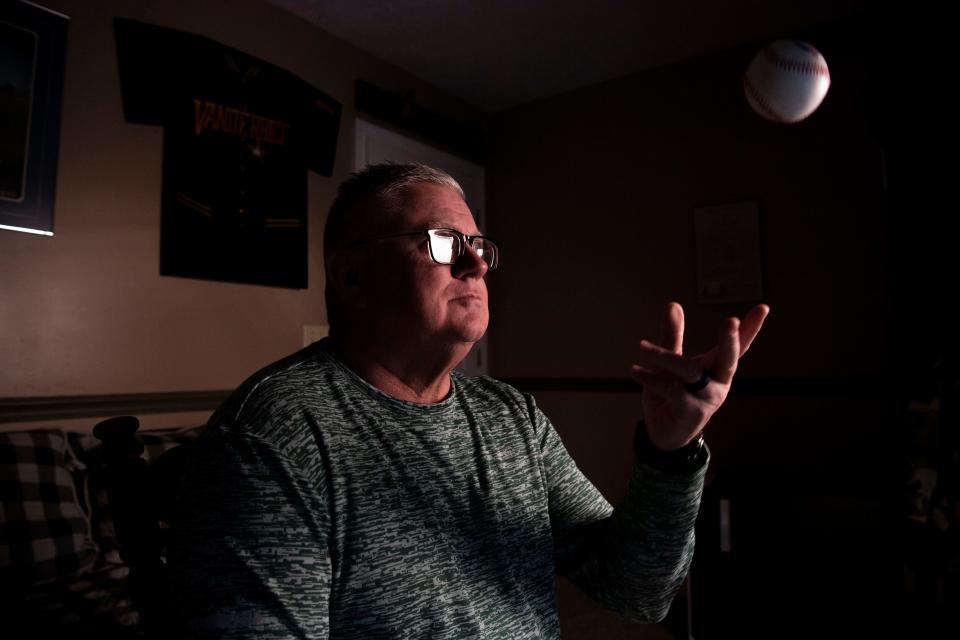

The name belongs to a 60-year-old retired car salesman/broker. To a husband. To a father of two sons. To a youth baseball umpire.

The binder rested to Edwards' right on a table at a burger bar in Mt. Juliet.

He was hesitant to open it. The start of Major League Baseball's 2024 season was a few weeks away.

Jeff Edwards' chances at his opening days seemed so far away.

"I don't want to be a guy who almost was, but wasn't," he said.

Twenty-nine years, 11 months had passed since his major league dreams died for the final time. The Old Hickory native twice was chosen in MLB's amateur draft, once spent 33 days on a big-league roster but didn't play, and twice more came within 24 hours of playing in the big leagues.

"Who, honestly, would even care about some washed-up minor leaguer?" Edwards asked. "Nobody even really knows who I am."

An open book opens a book

Jeff Edwards is a man who was unsure on this March day whether he wanted to wake up his long-lost baseball longings.

"I just dug it out this morning for the first time in forever," he said of the binder that for decades had been buried in a cardboard box in his Mt. Juliet home, save for the few times his sons sneaked a peek.

Edwards' mother, a registered nurse named Camille, inventoried every newspaper clipping that so much as mentioned her son's name. They ranged from his high school days at DuPont, to his college days at Vanderbilt, to his professional days in the minor leagues with the Los Angeles Dodgers, Houston Astros and Cleveland Indians.

Jeff Edwards finally opened the book, finally flipped through those pages.

There, he found the answer to his own question.

"Who, honestly, would even care about some washed-up minor leaguer?"

'I don't think I ever called a pitch for him'

Affixed to the first page was a grainy, black-and-white picture of the 6-foot-2 left-hander in mid-pitching motion. On the second page was another picture of Edwards and some Huffine Rebels teammates from the Aug. 9, 1979 edition of the Nashville Banner, before the team headed to a Mickey Mantle tournament in Knoxville.

He flipped some more.

"Jeff Edwards MVP in Baseball" a headline read.

"Dupont's Edwards Leading Bulldogs" read another.

On page 76, two of his minor-league baseball cards from his time with the Canton-Akron Indians.

On the other side of that page, the $10,000 check stub from the Dodgers, postmarked Jan. 21, 1985, and the letter informing him it was the final payment of his signing bonus. Both were tucked inside the original envelope.

All the letters had envelopes.

The Western Union Mailgram dated Aug. 6, 1980, from the Cincinnati Reds, inviting him to a professional tryout on page 21. The handwritten recruiting letter from Alabama assistant coach Roger Smith postmarked March 24, 1981 on page 33.

Handwritten letters, tryout invitations, none of it was necessary for Edwards' high school coach, Pete Bush. He sort of lucked into coaching the kid with the fastest fastball around when he took the DuPont job at a time when he "knew nothing about baseball."

Bush knew enough, though, to recognize what was before his eyes.

"Back then we didn't know at DuPont what a radar gun was," he said. "He threw extremely hard.

"I didn't really bother Jeff a whole lot. Kind of worked on the mental parts of the game . . . I don't think I ever called a pitch for him."

The most appropriate place to begin the story of Edwards' baseball journey, though, might be the end.

The final comeback

The year was 1995. Edwards was 31. His fastball, once in the mid-90s, by then topped out at 87 mph.

He hadn't throw a pitch professionally in five years. A torn rotator cuff was the culprit that cost him his career.

So he thought.

Major league players were still on strike in a labor dispute with owners when spring training rolled around.

Edwards happened to be visiting his son in Florida. He learned teams were looking for players. He showed up to the New York Mets' camp in Port St. Lucie.

A headline on page 3 of the sports section in the March 29, 1995 edition of The Tennessean begins to explain.

"Back in the bigs. Ex-Vandy pitcher enjoys it while it lasts"

"It's not a resurgence of a career," Edwards told reporter David Jones in the story under that headline. "It's to do something different for a while."

Those words came out of his mouth three days before his final professional pitch came out of his left hand, a pitch that came with a catch.

Edwards was a replacement player, or "scab," who had made the Mets' opening day roster only because the "real" players were on strike.

"We all knew it was a farce," he said of being a scab. "The owners were just trying to piss off the players."

His baseball end was near. Edwards sensed it.

Strike three: 'And we're done'

The Mets were wrapping up their six-week camp with an exhibition game at then-Jacobs Field in Cleveland on March 31, 1995.

"After that game we were going to get on a charter flight to Miami and open the season the next day against the Marlins," Edwards said.

He was going to be a big leaguer within 24 hours.

But Edwards began to notice around the fifth inning of that exhibition that both teams were changing pitchers at a rapid rate. He suspected something was amiss.

"They told me to get up in the seventh," he said. "I looked at the guy beside me and I said, 'The strike's over, because he's pitching everybody and I don't know why he'd do that the day before the season.' "

Edwards' suspicions were confirmed after the game in the locker room, where general manager Joe McIlvaine informed the players the jig — and Edwards' gig as a big leaguer — was up. MLB players were coming back to replace the replacements. The strike had been resolved.

"You'll need to clean out your lockers and it was nice knowing you and you'll have a check waiting for you at the office," Edwards said McIlvaine told the team. "And we were done."

Edwards flew to Florida that night and the next day collected his belongings from his locker in Port St. Lucie.

He picked up his $10,000 check in a conference room of a Holiday Inn, turned the key in his gray 1988 Toyota Land Cruiser and pressed the gas pedal back home to Nashville, stopping along the way to drop off teammate Lou Thornton in Birmingham, Alabama.

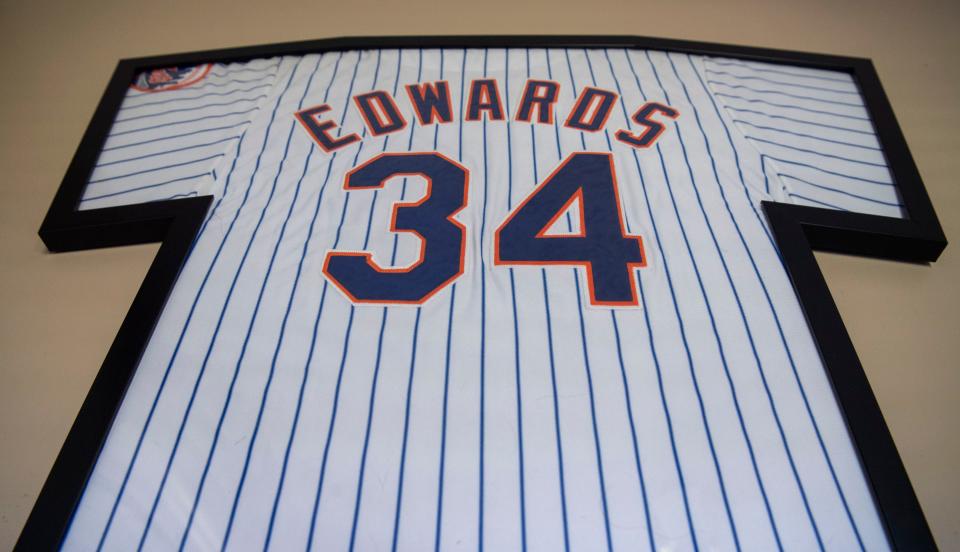

The only physical evidence of his time with the Mets is a framed No. 34 jersey that hangs in the guest room of his home.

Baseball was done with Edwards for good.

Strike two: 'I was hoping it was you'

Rewind five years to 1990, the second time baseball was done with Edwards.

He was 26 and still had his fastball. Until he didn't.

He was in Cleveland, at old Municipal Stadium, where he happened into a hello with a roving coach/instructor named Dallas Williams.

"I was hoping it was you we called up," Edwards recalled Williams saying that day.

Edwards' left rotator cuff — and his spirit — was torn.

"I'm hurt," Edwards replied. "I'm here for medical treatment."

He had just had his best start of the season with Triple-A Colorado Springs. The major leagues seemed inevitable.

Instead, his season, and his playing career, was over.

So he thought.

"I think I might have been getting called up, but they didn't tell me because I got hurt," Edwards said.

He had played seven minor-league seasons with eight teams. He had spent at least parts of six seasons at the Triple-A level. He'd proven himself.

Now the time had come to go home.

Strike one: 'Enough was enough'

The aspirin, the anti-inflammatories, the hope — none of it was enough to keep Edwards' secret.

The combination was just enough to keep him from reaching the big leagues for the first time.

It was 1987. Edwards was 23. He'd made the Houston Astros' roster out of spring training and traveled with the team for a little more than a month to start the season.

"I had finally made it to the big leagues," he later told Phil Bowman of the Canton (Ohio) Repository News.

He never played.

His aching left shoulder, the one that had gotten him this far, had sent him back to Triple-A. Undiagnosed bone spurs were the culprit.

The pain kept him in Triple-A the rest of that season.

By spring training 1988, the Astros decided "enough was enough," according to Edwards. It was time for surgery. Doctors discovered the bone spurs, which wrecked his bursa sac.

He was traded to Cleveland the next season.

But Edwards' major league hopes remained intact.

He was even part of a 20-player "Diamond Diplomacy" team picked by then-MLB commissioner A. Bartlett Giamatti to spend three weeks teaching baseball in the Soviet Union in 1989.

Jeff Edwards, the Earlier Years: Strikes out 20, throws 200-plus pitches

Rewind to spring 1981. Edwards was 18. He was playing for DuPont High. He was headed for Vanderbilt.

He struck out 20 batters and threw well north of 220 pitches in 14 innings in one game played at two sites that day and night.

The score was tied 1-1. Seven or eight innings were in the books when darkness swallowed the sky over DuPont High, prompting both teams to pile on a bus and head 10 miles to McGavock to finish what they'd started.

Edwards wanted to finish what he started that day, too.

Bush obliged.

"I said, 'How do you feel?' " Bush said. "He'd get a little excited and get a little tongue-tied. He finally said, 'Let me go. Let me go, Coach. I'm ready.' "

McGavock scored seven runs in the 17th inning, three innings after Edwards left the mound in a game McGavock coach Mel Brown described to The Tennessean as "the kind of game you'll tell your grandchildren about."

Edwards finished that season with a 3-1 record and a 0.80 earned run average. Was voted NIL player of the year. He was chosen by the St. Louis Cardinals in the 21st round of the draft that summer but opted instead for college.

Three years later, he was picked in the seventh round of the 1984 MLB Draft by the Los Angeles Dodgers.

'I wish I could say I had $100 million in the bank'

There's a cost that comes with digging up dreams that almost were.

Edwards knows nostalgia can a seductive liar.

That's why he was hesitant to open that old blue binder.

Edwards also knows most of the important moments of his life are not preserved in that binder.

After baseball, he settled into the car business. He divorced after having his first son, Austin. He remarried, to a woman named Molly, on Feb. 8, 1997. They had Jeff's second son, Robert, who is named after Jeff's father.

Funny story about Jeff and Molly, who are still married 27 years later: A dead cell phone battery brought them together. They reconnected when Jeff was at a Cellular One store to replace said battery and heard a familiar name over the store's intercom: Molly, who was an account manager.

She also is Edwards' former DuPont classmate.

"I came clean and said, 'I need a battery and your number,' " Jeff said.

Baseball by now was a lifetime ago. The majors never did come to pass.

"I wish I could say I have $100 million in the bank, that I've got 100 wins under my belt," Edwards said. "I would feel better about that.

"But I know I'm in the 1% of people ever to step foot on a minor-league field, maybe less than 1%. It wasn't in my control. I learned that."

He's lived with that.

He's OK with that.

The last photo in the blue binder showed the end of baseball. It was the last thing tucked under yellowed plastic. Edwards and 13 other players were dressed identically in blue and orange Mets uniforms.

He closed the book and set it on the table.

Baseball had taken Edwards across the country, to almost all 50 states, he said.

Baseball always brought Edwards back home.

This article originally appeared on Nashville Tennessean: Former Vandy pitcher Jeff Edwards just missed playing MLB three times