There's only one way to save the Great Barrier Reef: Fight climate change

The Great Barrier Reef is in serious danger of dying, and stopping global warming could be the only way to save it.

In 2016, a world-wide coral bleaching event devastated the reef, especially in its pristine northern reaches where the effect was deemed "catastrophic." Now, as the reef faces yet another bleaching event in 2017, a new report has found only one way to rescue the natural wonder: Fight climate change.

SEE ALSO: Looking for hope on climate change under Trump? Cities are where the action is.

Published in Nature, the research assessed the scope and severity of bleaching on the 2,300-kilometres-long (1,429 miles) reef in 2016, compared with past events in 1998 and 2002.

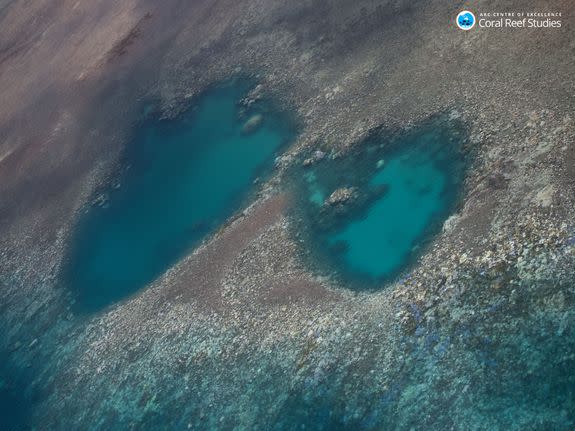

Aerial surveys of more than 1,100 reefs across the area revealed the extent of the damage caused by record high water temperatures — the result of a strong 2015-2016 El Niño and human-caused global warning.

Image: Greg Torda, ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies

The numbers are incredible: In 1998 and 2002, only about 10 percent of the surveyed reefs were in the extreme bleaching category (meaning more than 60 percent bleached), said Sean Connolly, a professor at the ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies. In 2016, nearly 50 percent of the surveyed reefs were in the extreme category.

Likewise, only 8.9 percent of 1,156 reefs surveyed escaped its effect in 2016.

Coral bleaching occurs when coral expels the colour and nutrient-giving algae that lives in its tissue. Caused by stresses such as increased water temperatures and pollution, this leaves the skeleton exposed, making it vulnerable to heat, disease and pollution.

Without reducing carbon emissions, we are giving our reefs no time to recover from bleaching events — events that are predicted to occur with increasing frequency. It takes around 15 years for relatively fast-growing corals to recover from a significant disturbance like bleaching or a cyclone, Connolly explained.

"There just won't be time for reefs to recover," he said. "How badly they degrade depends very much on how quickly we move to a zero emissions economy. Once global temperatures stabilise, then reefs will have time to adapt and catchup."

Image: James Kerry, ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies.

Image: JAMES KERRY, ARC CENTRE OF EXCELLENCE FOR CORAL REEF STUDIES.

Robert H. Richmond, a research professor at the University of Hawaii's Kewalo Marine Laboratory who was not involved with the report, said the paper's findings were sobering but not surprising.

The most recent global bleaching event was "unprecedented in recorded history," he said. "We're seeing these happening more frequently, they're longer lasting and the geographic distribution is spreading."

The report also found we cannot climate-proof reefs with only local measures. Water quality management, such as preventing agrochemical runoff and implementing fishing bans, for example, won't necessarily protect reefs from the effects of climbing ocean temperatures.

Image: Greg Torda, ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies

"That doesn't mean water quality doesn't have an important impact on reefs," Connolly added, explaining that sediment and algae caused by runoffs can make it harder for baby corals to grow. "The point is not that addressing water quality is useless, but that it doesn't protect us from the negative effects of climate change."

This finding calls into question whether the Australian government's Reef 2050 Long-Term Sustainability Plan, which focuses largely on water quality and reducing the impact of ports and shipping on the reef, will do much to mitigate large-scale bleaching.

Image: Terry Hughes, ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies

While past researchers have hypothesised that reefs exposed to bleaching might be able to adapt and survive future such events, the team did not see that in the data. "Bleaching is an episodic event," Connolly said. "The pace of temperature change is very, very fast. It doesn't seem to be the case that corals are able to adjust their physiology to warmer water so that they have higher bleaching thresholds."

There's no question that coral reefs are severely threatened, Richmond said, but they're not doomed if climate change can be halted.

Authored by 46 scientists, the report asks the world to take notice. "Things are changing even faster than many of us feared," Connolly added. "We can keep burning fossil fuels or we can try to protect functioning coral reefs.

"But we're not going to be able to have both."