Steve Ditko remembered: Spider-Man co-creator and legend of Marvel Comics

Steve Ditko, who has died aged 90, was an illustrator of remarkable flair whose colourful tales of superhuman characters made him one of the most innovative and revered artists in the world of comics. He also worked in the fantasy and horror genres and created an array of other heroic figures but he was known above all for creating the visual image of Spider-Man.

The idea for a superhero with spider-like qualities was first floated by Jack Kirby, one of the creative forces behind Marvel Comics. In 1962, editor-in-chief Stan Lee began to develop the idea but did not like Kirby’s illustrations.

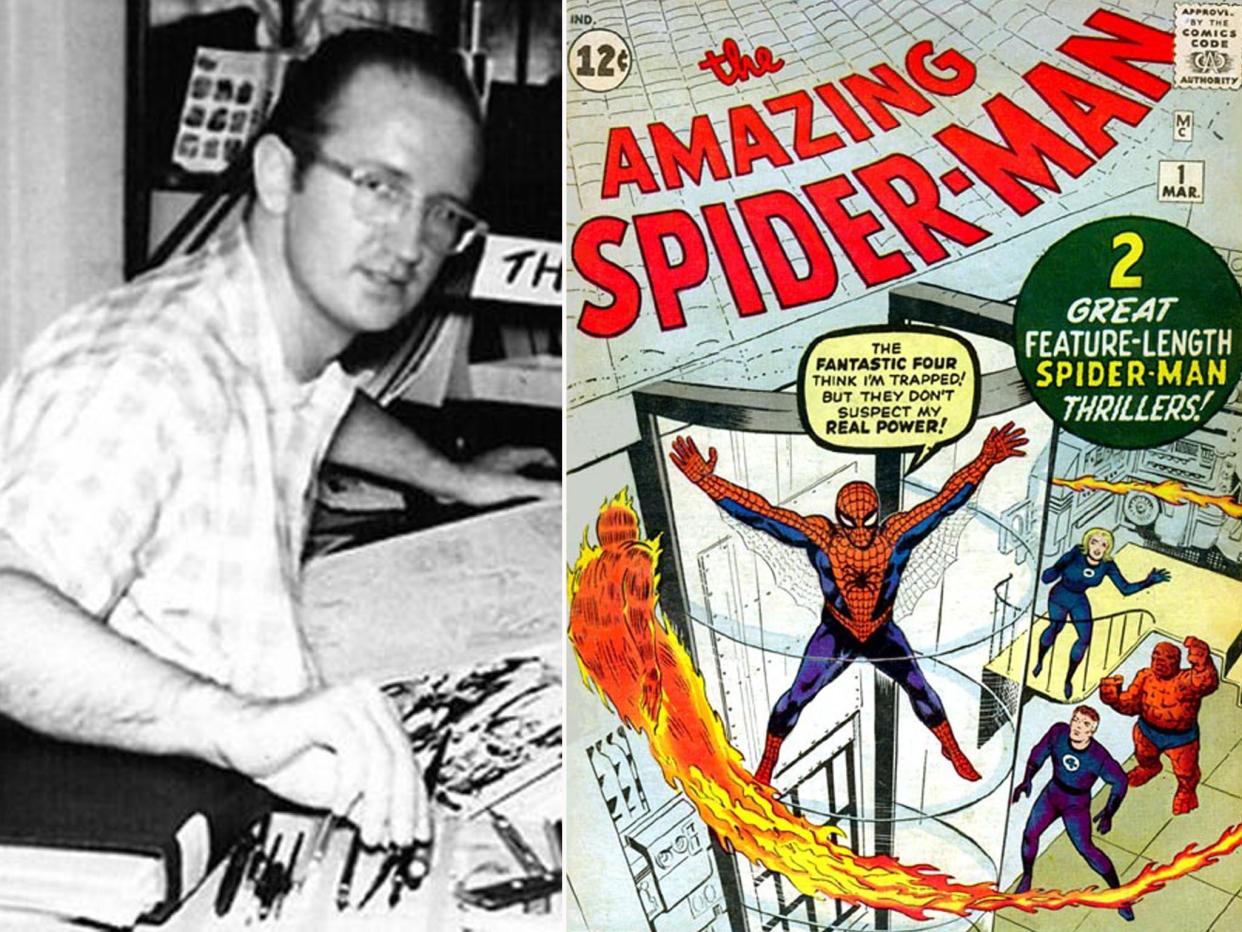

Lee then asked Ditko, who had been working on and off with Marvel for several years, to give visual form to Spider-Man. The first appearance of Spider-Man came in August 1962 – during what aficionados call the silver age of comics – in Amazing Fantasy.

The story centred on teenager Peter Parker who acquired remarkable powers after being bitten by a spider. In his blue-and-red tights and mask – devised by Ditko – Parker transformed himself into “The Amazing Spider-Man” who climbs walls, crouches on ceilings and uses a weblike material to swing among skyscrapers as he overcomes villains, such as the Green Goblin, Doctor Octopus and the Sandman.

Ditko supplied the illustrations and, eventually, much of the storyline of Spider-Man, while Lee wrote the dialogue. The comic proved to be so popular that it soon became a separate franchise and ultimately evolved into a daily newspaper comic strip and a series of Hollywood blockbuster films.

It was considered a monumental advance in comics because Peter Parker was an ordinary teenager, like many of the readers of Spider-Man, who struggled in school to be noticed by the popular crowd. Not even his beloved Aunt May knew of his secret, arachnid-derived abilities.

Moreover, there was an undercurrent of psychological depth because Peter Parker was forever haunted by the death of his Uncle Ben, which he could have prevented if he had used his “Spidey” powers.

“Ditko took what was a very good superhero comic strip and really turned it into something revolutionary,” Blake Bell, author of Strange and Stranger: The World of Steve Ditko, said in 2012. “It was Ditko who wanted to ground the strip in reality, to see what it was like to be a hero through the eyes of a teenager and to struggle.”

Comic-book historians often cite If This Be My Destiny from issue number 33 of The Amazing Spider-Man as something of a masterpiece of the genre. In that issue, from 1966, Ditko portrays a besieged Spider-Man practically crushed under heavy machinery. As water rises around him, he struggles to break free.

For three pages, in panels of different sizes, Ditko depicts Spider-Man having an existential battle, practically giving up before remembering his filial duty to his aunt and uncle.

“Everything going black,” Lee wrote in a caption. “My head – aching! Hold on – I must hold on!”

Finally, in a full-page illustration with dramatic foreshortening, Spider-Man lifts the machinery off and extricates himself: “From out of the pain – from out of the agony – comes triumph!”

Generations of illustrators have considered that issue of Spider-Man a model of visual storytelling, practically the comic-book equivalent of Citizen Kane.

After 38 issues of Spider-Man, Ditko parted ways with Lee and Marvel Comics in 1966. Fans have long speculated over the breakup, and Ditko never explained what drove them apart. In 1969, he stopped giving interviews altogether.

Years later, in an illustrated essay giving his version of Spider-Man’s origin, he wrote, “If all the web lines I’ve drawn were laid end to end, they still wouldn’t be enough to fit around Lee’s swelled head.”

Lee credited Ditko as the co-creator of the Spider-Man franchise, saying in 1999 that Ditko made the comic “more compelling and dramatic than I had dared hoped it would be. Also, it goes without saying that Steve’s costume design was an actual masterpiece of imagination. Thanks to Steve Ditko, Spidey’s costume has become one of the world’s most recognisable visual icons.”

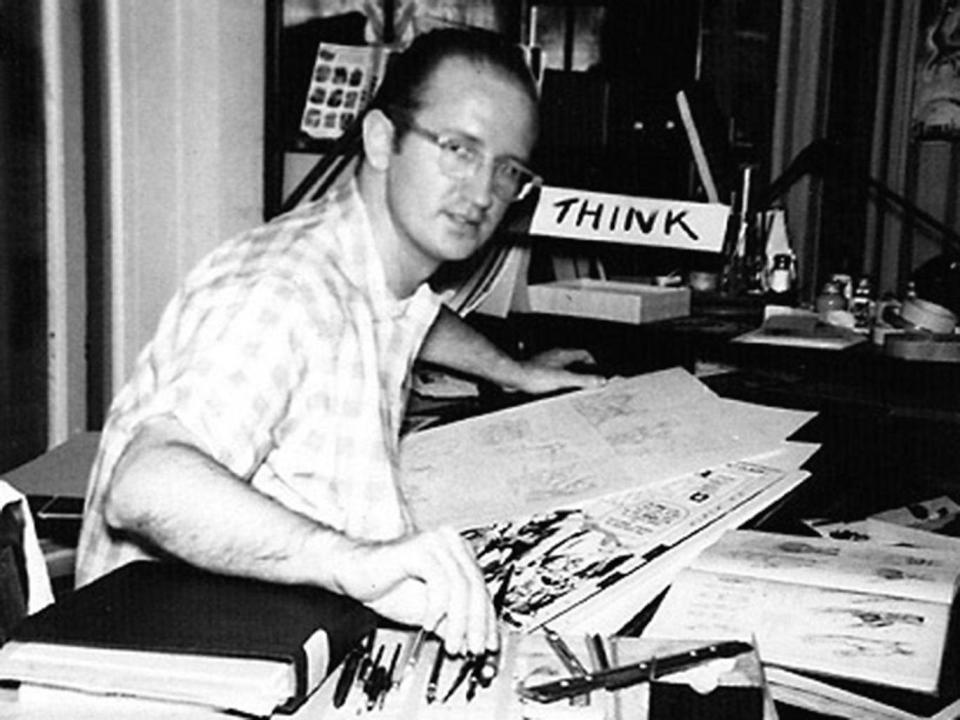

Stephen John Ditko was born on 2 November 1927, in Johnstown, Pennsylvania. His father was a carpenter in a steel mill with a love of comic strips.

According to Bell’s Strange and Stranger: The World of Steve Ditko, Ditko’s mother created scrapbooks of Prince Valiant comic strips for her husband.

Ditko served in the Army in Europe after the Second World War, then moved to New York in 1950. He used the GI Bill to attend a school for cartoonists and illustrators, where he studied under Jerry Robinson, one of the artists for Batman.

Ditko soon became a prolific contributor to comic books and fantasy magazines, most of them put out by the low-budget Charlton publishing company. In 1960, he created his first superhero, Captain Atom, an astronaut whose powers derive from exposure to atomic radiation.

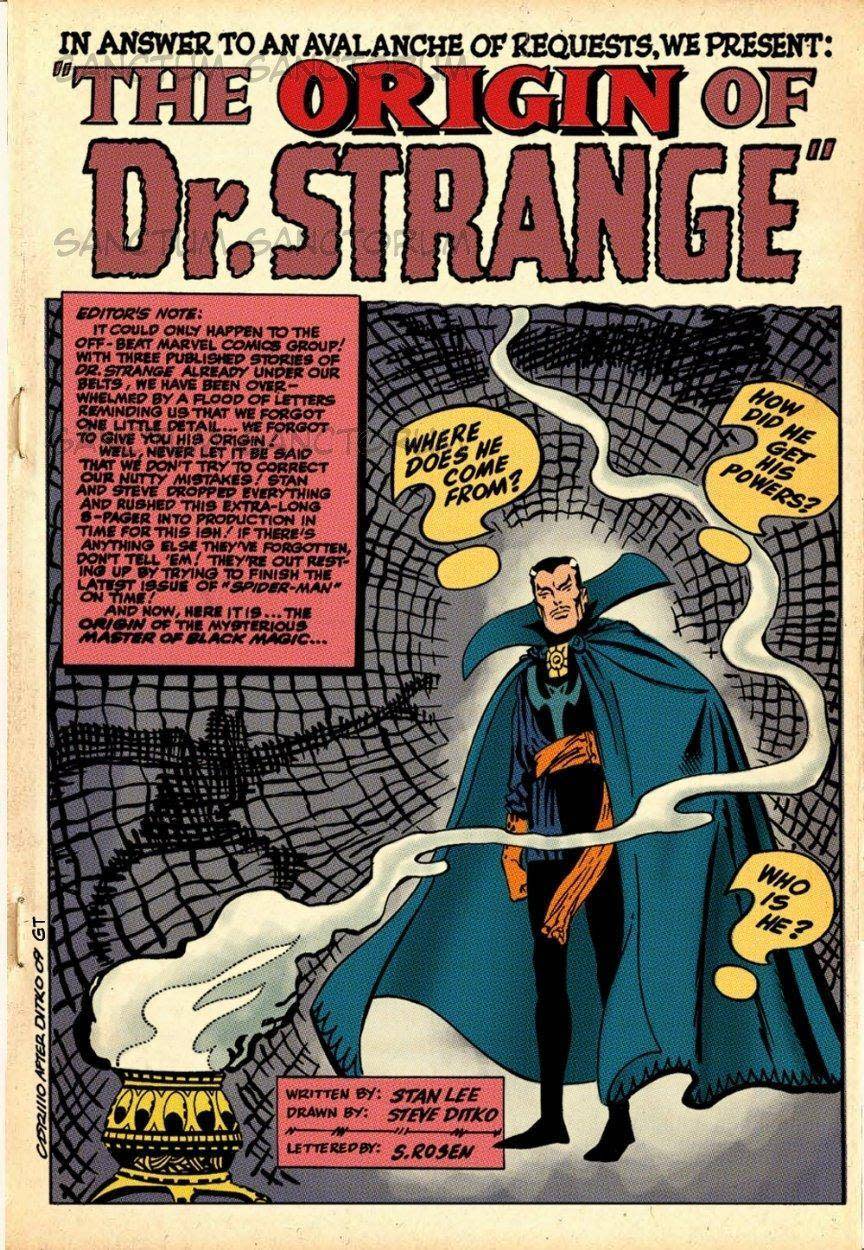

In 1963, Ditko created another Marvel superhero, Doctor Strange, a surgeon whose hands are injured in a car accident. Seeking to restore his abilities, he travels the world and eventually acquires an exotic caped costume and mystical powers to be used to benefit mankind. Benedict Cumberbatch starred in a 2016 film based on Ditko’s character.

After splitting with Lee, Ditko worked for DC Comics and other publishers, reviving earlier heroes, such as Captain Atom and a Blue Beetle, and creating several other comic books, including Creeper, Hawk and Dove and Question.

One of his characters, a vigilante known as Mr A, strongly reflected Ditko’s devotion to ideals propounded by novelist Ayn Rand, in which he saw the world in rigid terms of good and evil. He wrote many tracts based on Rand’s philosophy of objectivism and grew increasingly distant from old acquaintances.

When BBC television host Jonathan Ross and writer Neil Gaiman approached Ditko for a documentary released in 2007, he greeted them but refused to be quoted or photographed.

Survivors include a brother and a sister.

Ditko kept working at a small studio in Manhattan until shortly before his death. One of the few times he ventured out was when Craig Yoe, the creative director of Jim Henson and His Muppets, invited him to meet Henson and visit the Muppet creature shop.

Yoe later published five books about Ditko and his work. In every case, Ditko refused to help and refused to accept any money for his work – which, in any case, was the property of the companies he wrote for.

“All along, I continued to offer Steve involvement of any kind, monetary or editorial or otherwise,” Yoe wrote in a Facebook post. “He assured me he absolutely wanted nothing of the sort, but told me, ‘Keep doing what you’re doing!’”

Steve Ditko, comics artist, born 2 November 1927, died 29 June 2018

© The Washington Post