Is Stark County family man accused of genocide this generation's John Demjanjuk?

LAKE TWP. – Eric Nshimiye may be this generation's John Demjanjuk.

Each man was, or became, a model citizen while living in Northeast Ohio. Both were ingrained in their respective communities. Township resident Nshimiye is a 52-year-old engineer at Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co. in Akron; Demjanjuk was an auto worker from Seven Hills.

Nshimiye is a married father of four; Demjanjuk raised three children. Nshimiye is a member of St. Paul Catholic Church in North Canton; Demjanjuk worshipped at St. Vladimir Ukrainian Orthodox Cathedral in Parma.

Admirable, honest and decent, by most accounts.

"I can't say enough good things about (Nshimiye)," said Doug Chamlee, a public school IT manager in El Paso, Texas, and board member for a youth mentoring foundation Nshimiye created.

Neighbors of Nshimiye told a similar story last week. They said children played soccer in his yard. He mowed the lawns of senior citizens and assisted one in a wheelchair, helping the man navigate from a porch to a driveway.

But federal authorities aren't concerned with the man Nshimiye is now. Same went for Demjanjuk in his saga, which began in the 1980s and spanned four decades.

It's all about who they used to be.

They say he was a member of the National Revolutionary Movement for Development, the ruling Hutu-dominated party which incited the 100-day genocidal spree; that he belonged to Interahamwe, the party's violent youth wing; and that he wielded a spiked club and machete in the elongated melee against a minority group known as Tutsis.

It's an alleged evil past, same as Demjanjuk's.

By 1981, after 20-plus ho-hum years a U.S. citizen, Demjanjuk was effectively outed as "Ivan the Terrible," a Nazi guard who operated gas chambers at Treblinka during World War II, killing thousands of Jews.

He'd always denied it but was found guilty by an Israeli court. However, his death sentence was overturned in 1993 by that country's Supreme Court. New evidence had shown "Ivan" was a different man.

Demjanjuk came back to the United States, but freedom was temporary.

In 2009, he was deported again. A Munich court ruled that he helped kill 28,000 Jews at Sobibor extermination camp in Poland. Awaiting appeal, Demjanjuk died in a nursing home in 2012 at age 91.

Nshimiye's judicial journey has just begun and is to be played out in Boston.

It's unclear how it will end.

For now, though, the U.S. Department of Justice has charged him with three crimes. They accuse him of lying about his past to enter and remain in the U.S., and for lying during a 2019 federal trial in Boston, when he testified on behalf of a former Rwandan roommate, Jean Leonard Teganya, who also was accused of genocidal crimes.

Nshimiye was arrested on March 21. He was scheduled to appear Friday in U.S. District Court in Youngstown for a detention hearing. Charges against him are expected to be heard later in Boston.

Eric Nshimiye's family speaks out on his behalf after Rwanda genocide accusations

"The whole family is in shock," said one of Nshimiye's nieces.

Two members of his family spoke with and provided information to the Canton Repository, provided the newspaper agreed not to identify them. Although they said Nshimiye is wrongly accused, they are concerned for their collective safety.

"We don't know what's next, who's next," she said, explaining that their family, and many in the Rwandan community in the U.S., Canada and United Kingdom, are a tight, connected group.

She said her family, including Nshimiye, was never "into politics" when they lived in Rwanda. Yes, there were Hutus (about 85% of the 13.5 million population) and Tutsis (14%). But she said it was never talked about or an issue of any sort.

"They wear the same clothes; they eat the same food; they marry each other," she said.

The niece said Nshimiye has spoken with his wife on the phone from jail in Mahoning County. She added she can barely fathom what her uncle is thinking, locked behind bars.

"He's such an amazing person being crucified," she said. "Maybe God is using Eric to finally just stop a lot of injustice going on. ... Imagine he's feeling like he's there for a purpose."

Earlier this week, Nshimiye's family sent a letter to the Repository.

In it, they wrote that Nshimiye's name never surfaced in a prior United Nations International Tribunal for Rwanda. Nor did it come up in a Human Rights Watch investigation, or in local Gacaca courts, the post-genocide transitional Rwanda justice system.

"Only after he agreed to act as a defense witness (during Teganya's 2019 trial) did these false accusations arise, and those familiar with the Rwandan judicial system know exactly why," the letter stated. "If you dare question the official Rwandan narrative, you become a target and it's sad the U.S. federal prosecutors are doing Rwanda’s bidding using U.S. taxpayers' money."

During Teganya's trial, Nshimiye also submitted a letter on his old roommate's behalf to the court.

In it, Nshimiye said the two had met as high school seniors in the Rwandan capital of Kigali in 1991. Both, he wrote, earned scholarships to the National University of Rwanda, Butare campus, where they studied pre-med. Teganya, he said, was a friend and role model.

"We shared several friends, both Tutsi and Hutu and he was best known to get along well with everybody," Nshimiye wrote, adding that both men fled Rwanda in 1994 because of "dangerous conditions."

"I was fortunate to find an asylum in the U.S. in 1995," Nshimiye wrote. "We lost contact of each other for quite a long time until a friend of mine informed me (Teganya) was living in Canada. I managed to get his telephone number and we got in touch again. ... I stayed in touch with (him) ever since."

Federal prosecutors see it different.

After all, Teganya ultimately was convicted on some of the same kind of charges Nshimiye now faces. If Teganya lied, that must mean Nshimiye lied, too. And only recently did witnesses identify exactly where Nshimiye allegedly killed men, women and children 30 years ago.

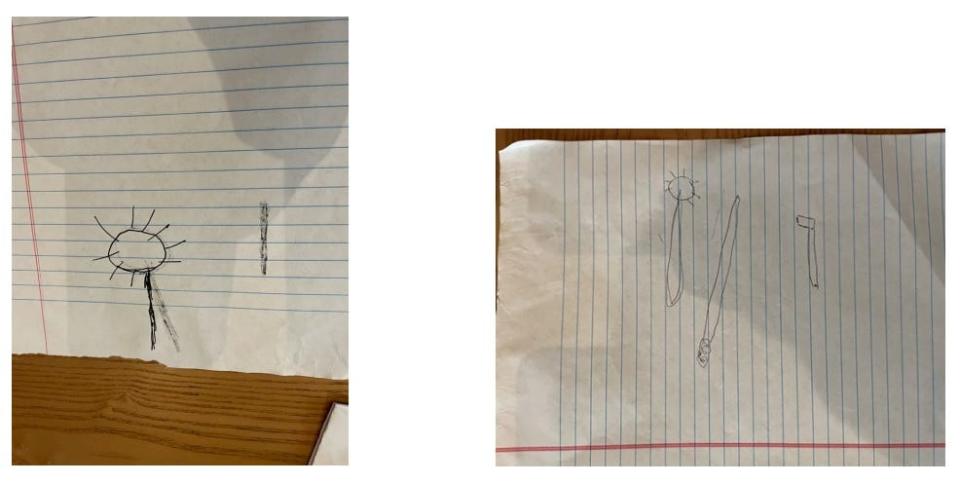

They even drew pictures of weapons he used, according to a U.S. Homeland Security agent affidavit within court records.

The engineer, family man, mentor and Catholic

A combination of court documents, interviews with family members and others, along with public records, provide an outline of Nshimiye's life and times in the U.S.

All of it, though, came after he'd allegedly lied about his past to U.S. immigration officials in Kenya in 1995, according to some of the criminal charges leveled against him.

Nshimiye was granted refugee status and U.S. work privileges in late 1995. He entered the country in New York. He settled in Ohio, earning an engineering degree at the University of Dayton.

Along the way, he was approved as a lawful permanent resident in 1998, then eventually a naturalized citizen in 2003. Problem is, he told the same lies about his past, authorities allege.

Nshimiye had been hired at Goodyear in 2000. A company spokesman recently said that "Goodyear is deeply troubled to learn of the recent charges brought against one of our associates and is fully cooperating with authorities."

After a brief time living in Summit County, Nshimiye and his wife bought the home in Lake Township in 2003. The young family grew to include four children.

Their two sons were exemplary students and athletes at North Canton Hoover High. One went to Harvard, the other to Duke. Their two daughters remain in the school system.

"I want my kids to grow up like Eric's children," his niece said.

Another family member provided the Repository photos of Nshimiye — one of him standing near his house, with a side yard soccer goal in the background; the other of him standing inside St. Paul Catholic Church in North Canton.

The Nshimiyes, the niece said, are devout Catholics.

The family is one of four profiled on the church's website. Along with a photo of the family of six is a summary, in Nshimiye's own words, of how they landed at St. Paul.

He explained they had been members of Immaculate Heart of Mary in Cuyahoga Falls. They made the switch to St. Paul in 2003 after they moved into their Stark County home.

Nshimiye lauded the welcoming spirit of the parish, and the fact that names of celebrant priests and deacons always are announced during each Mass to those in attendance.

"Another reason that my family loves St. Paul parish is that deacons are used extensively," he wrote. "The parish has five of them. ... This provides additional flexibility to our parish and some relief to our priests since they must celebrate so many Masses."

Nshimiye's oldest son is now a postulant in the seminary, studying to become a priest.

In the last few years, Nshimiye purchased houses on Pittsburg and Demington Avenues NW in Plain Township. Both appear to be rentals, based on recent listings.

He also created the Ntibarwiga Family Foundation, a private charity that operates its own youth mentoring program. It also provides academic scholarships to needy students and emergency financial support, according to information on its website.

Chamlee, the school IT employee in El Paso, met Nshimiye because of the foundation. Chamlee said his wife has a business relationship with a Nshimiye family member who serves on the foundation.

"I'm just dumbfounded," Chamlee said of the accusations against Nshimiye. "We mostly interacted in (Zoom meetings), but he seemed like the greatest guy. Very supportive ...."

And Nshimiye always was cool and calm, said Erwin Gutic, a graduate student at Ohio's University of Rio Grande.

Gutic played basketball at Malone University before graduating last year. A native of Sarajevo, Gutic was asked to join Nshimiye's foundation board years ago, after they'd met at a Jackson Academy of Global Studies program at Jackson High School.

"He's obviously a very good family man," said Gutic. "They are all very well-connected, his family. And everything they do for that (foundation) comes from a very good place."

Gutic said he didn't know Nshimiye had been arrested on March 21 until days later. The first thing he read was the family's statement, denying the allegations against him.

"Then I spent the whole night reading all the other stories ... surprised like everyone else," Gutic said.

Detailed accounts of alleged killings by Eric Nshimiye during 1994 Rwandan genocide

The Rwandan genocide began on April 7, 1994, the day after Rwanda President Juvénal Habyarimana and Burundi President Cyprien Ntaryamira ― both Hutu — died when their plane was shot down.

Matthew Langille, a Department of Homeland Security special agent, had investigated Nshimiye in recent years, according to his court affidavit. He noted that he'd interviewed eyewitnesses in Rwanda, including former student workers at the hospital where Nshimiye and Teganya worked during pre-med studies in 1994.

The document detailed some genocidal crimes Nshimiye allegedly committed, including that he:

Used a machete and spiked club to murder a 14-year-old Tutsi boy, a short time after Nshimiye and others had killed the boy's mother.

Along with a group of Interahamwe, rounded up 25 to 30 Tutsis hiding in the forest near the university. The group killed all of them, then burned their bodies in the forest.

Instructed Interahamwe members to rape and then kill six female university students. When he returned to find them alive, he struck one woman in the head with a nail-studded club, then hacked her to death.

Captured a Tutsi tailor who made coats for doctors at the hospital. Nshimiye and others took the tailor away. Nshimiye, carrying a blood-soaked spiked club, returned later. He bragged about how he'd killed the tailor.

Langille wrote that interviewees told him Nshimiye and Teganya "were frequently seen together before the genocide and during the genocide in Butare ... were widely known members of the MRND at the university and hospital prior to the genocide and regularly wore MRND attire including the MRND hat, scarf and other MRND items .... (and) participated in Interahamwe combat training in the forest adjacent to the university in the evenings ...."

The agent accused Nshimiye of lying about all of those facts when he testified at Teganya's 2019 trial.

Langille went on to explain that he met Nshimiye at his Akron workplace for an interview on March 11.

"I asked him a number of questions about how he came to the United States, how he survived the genocide, his political affiliation prior to the genocide, whether he had been a member of the MRND, whether he had been a member of the Interahamwe, and whether he had been at the university in Butare during the genocide," Langille wrote.

Nshimiye, he said, again spewed lies.

"Nshimiye also falsely denied being in Butare during the genocide, falsely claiming to have left Rwanda shortly after the president’s airplane was shot down," the agent wrote.

"When ultimately asked if he had been involved in raping or killing anyone during the genocide, Nshimiye first responded by shaking his head, laughing nervously, and asking for a drink of water. When I persisted ... he falsely denied any involvement ...."

Ten days after that session, on the date of Nshimiye's arrest, federal authorities released statements to the press.

Details appeared on news outlets around the country and world. Eric Tabaro Nshimiye, aka Eric Tabaro Nshimiyimana, was charged with falsifying, concealing and covering up a material fact by trick, scheme or device; obstruction of justice; and perjury.

“For nearly 30 years, Mr. Nshimiye allegedly hid the truth about crimes he committed during the Rwandan genocide in order to seek refuge in the United States, and reap the benefits of U.S. citizenship," acting U.S. Attorney Joshua S. Levy said in a news release.

"Our refuge and asylum laws exist to protect true victims of persecution — not the perpetrators. The United States will not be a safe haven for suspected human rights violators and war criminals ...."

'His good name will be cleared'

Nshimiye's niece said she believes those who killed innocents during the genocide should pay for their crimes. However, authorities have the wrong guy, she said.

She said her uncle's appointed public defender was to handle Friday's hearings in Youngstown. She said a private attorney will take over after that.

The family said it will cost an estimated $200,000 to begin. They have started a GoFundMe page, which showed more than $16,000 in donations in its first three days.

Using the hashtag #truthandsolidarity, the family asks donors to advocate and fight for truth for Nshimiye.

"Our family vehemently denies all allegations brought against Eric and asserts his complete innocence," they wrote on the page.

"We express our heartfelt gratitude for the overwhelming support that Eric has received from friends and the community at large. Together, we will see this through and Eric will emerge victorious. His good name will be cleared, and his integrity restored."

The letter Nshimiye sent to the court on behalf of Teganya in 2019 reads like one he could write for himself now.

"(Teganya) is an innocent man who is being subjected to character assassination," Nshimiye wrote at the time, adding that his friend should have been applauded for helping people at the hospital.

"However, I believe in the American legal system to be truly independent and remain hopeful that the court will ultimately find out that (Teganya) is a good man who deserves to be free and allowed to pursue his dreams and take care of his family."

Reach Tim at 330-580-8333 or tim.botos@cantonrep.com.On X: @tbotosREP

This article originally appeared on The Repository: Community defends Eric Nshimiye, Ohio man accused of Rwandan genocide