How the Spurs have slowed the Rockets' high-flying offense

The Houston Rockets offense is mortal. That is now a certainty. But if you’d have been plopped in front of a basketball game for the first time in your life this past Monday night, you’d have been forgiven for thinking otherwise.

The Rockets blitzed the San Antonio Spurs, the NBA’s best defense, in Game 1 of their Western Conference semifinal matchup. They poured in 126 points in a 27-point blowout on the road, and had rational people believing that the series could turn into a bloodbath. They bombarded the Spurs with 22 3-pointers. The Daryl Morey-Mike D’Antoni basketball revolution was seizing power, and the Spurs were in danger of being its first high-profile victim. They were in trouble. They might have even been done. Finished. Kaput.

And then they weren’t.

Then they put together two extraordinary defensive performances, and all of a sudden have a chance to go up 3-1 in the series Sunday in Houston. They held the Rockets to a season-low 92 points in Game 3. They held the league’s second-best offense — one that at one point broke the century mark 61 games in a row — under 100 points in back-to-back games for the first time all season. They turned the narrative on its head.

So how have they done it?

Make-or-miss league

With 6 minutes and 20 seconds remaining in the third quarter of Game 3, James Harden ambled up the Toyota Center floor, the basketball at his fingertips, and the Spurs at his mercy. He crossed over to set up a Clint Capela screen, turned the corner and bore down on the lane. He then flung a one-handed cross-court pass to an expectant Trevor Ariza, who caught the ball with his defender still in the painted area. In rhythm, Ariza rose up, untroubled by a late close-out, and unleashed a 3-pointer.

He missed.

The shot was straight out of the Morey-D’Antoni-Harden basketball factory, a picture-perfect look at the rim. Yet it just didn’t fall.

You’ve probably heard the cliché that the NBA is a make-or-miss league. The secret about clichés is that, at least to some extent, most of them are true. Shot-making determines so much in basketball, and it has determined a whole lot in this series. The Rockets shot 44 percent from 3-point range in their rampant Game 1 win. They fell to 32.4 percent in Game 2, and dipped even further to 30.8 percent in Game 3.

The disparity wasn’t all about shot quality either. Houston hit 59.3 percent of catch-and-shoot threes in Game 1 compared to 40 percent in Game 2 and 31.3 percent in Game 3. More tellingly, it shot 50 percent in Game 1 on 3-pointers with the closest defender between two and six feet away — the middle range of NBA.com’s contested/uncontested continuum. In Game 2, it hit just 28.6 percent of such shots. In Game 3, it was at 34.5 percent, and was 5 for 24 on “open” or “wide open” threes (with the closest defender over four feet away).

Especially in the first half of Game 3, the Rockets missed a number of shots that they’d expect to make. They not only missed threes, they missed a collection of floaters, mid-range jumpers and contested layups that often fall through the net at a higher rate.

After Game 1, with the external freakout kicking into high gear, Tony Parker was asked to explain what had just transpired. “They shot the ball very well,” he said. “We didn’t.” That was all. And to some extent, Parker was right. The intimation, of course, was that shooting would regress to the mean, and the series would even out. And it has.

But this hasn’t been all about make-or-miss. There are perceptible, quantifiable things that the Spurs have done to slow down the league’s second-best offense. And in a way, the Ariza miss from above is a perfect example of most of them. That’s because almost everything about the play, aside from the shot itself, was an outlier among San Antonio’s many outstanding defensive possessions in Games 2 and 3.

San Antonio’s best defensive adjustment has been its offense

The very first problem for the Spurs on that third-quarter possession was a missed shot — their own missed shot. LaMarcus Aldridge left his turnaround jumper short, and in doing so left San Antonio stuck with cross-matches. But more on that later.

The missed shot also prevented San Antonio from getting set — a condition the Rockets have taken advantage of all year. They love to push the ball. They got up 23.6 percent of their field goals this season in the first six seconds of the shot clock, the second highest rate in the league, and compiled a 59.5 effective field goal percentage on those early shots. The efficiency is inflated by steals, of course, but a good portion of the early shots come after opponent misses, too.

One of the biggest issues for the Spurs in Game 1 was that those misses were plentiful, and thus Houston’s opportunities to attack before San Antonio’s defense was set were also plentiful. Houston scored 27 fastbreak points in Game 1. Of its 87 total field goal attempts, per NBA Wowy, 31 came after defensive rebounds, and its effective field goal percentage on those attempts was 64.5 percent. That’s 40 points right there.

In Game 2, the Rockets were similarly effective after defensive rebounds (63.9 eFG%), but simply didn’t get as many opportunities to be effective. The Spurs couldn’t miss — they scored 1.36 points per possession — so the Rockets only grabbed 23 defensive rebounds compared to 42 in Game 1. Only 18 of their 83 field goal attempts came after defensive boards, and they tallied only 13 fastbreak points.

Game 3 was in some ways similar, and in some ways even worse for Houston. It again pulled down a relatively low number of defensive rebounds, but this time its effective field goal percentage on 17 attempts after defensive boards was just 44.1. Its fastbreak point total was a measly seven despite swiping 12 steals.

The Spurs played exemplary transition defense in Game 2 and especially Game 3, and ensured that Harden and the Rockets had to manufacture much of their offense in halfcourt sets. But the first step was improving on offense themselves.

“I don’t think we executed in a very wise manner,” Spurs coach Gregg Popovich said after Game 1. “We disobeyed a lot of basic basketball rules that they can take advantage of. If we’re going to shoot quickly and shoot poorly, that’s going to be a fastbreak all night long. And they’re better at that than we are. So we’ve got to play a lot smarter than what we played tonight.”

Essentially, the one true prerequisite for San Antonio’s masterful defensive gameplan was smart offense. The Spurs got smarter with the ball in Game 2, and that has allowed their defensive execution to become the story of the series ever since.

Kawhi Leonard

Before we get into philosophies and X’s and O’s, no analysis of San Antonio’s defense is complete without an ode to Leonard. Nothing they do would be possible without without him. If there is one player who’s a one-man pick-and-roll coverage, it’s him. When he goes under screens, he has the length to still contest Harden’s threes. When he goes over, he has the strength to fight through the screen. When he trails, he has the speed, quickness and length to recover and challenge a Harden floater or layup from behind.

Leonard is the reason keeping Houston out of transition is so important. Because Harden guards Danny Green on defense, it can be difficult for Green to get back to his man after a missed shot or turnover. Whenever Harden gets to go at anybody other than Leonard, that’s a win for the Rockets. Only when Leonard is matched up with his fellow MVP candidate can San Antonio stifle Houston in the halfcourt.

Defending Moreyball

It’s no secret what Houston wants to do on offense. Statistically, the most efficient shots in basketball are at the rim and behind the 3-point line. Houston wants the most efficient shots in basketball. And, more often than not, it gets them. During the regular season, a remarkable 81.7 percent of the Rockets’ shots were taken from either the restricted area or beyond the arc, by far the highest percentage in the league. It was extreme. And it was effective.

So what have Popovich and the Spurs done? They’ve gone to the corresponding defensive extreme. They’ve done everything in their power to both run the Rockets off the 3-point line and swarm them at the rim. After 84 percent of Houston’s shots were layups, dunks or threes in Game 1, only 72 percent were in Game 2, and 76 percent were in Game 3.

If the Rockets were running anything remotely resembling a traditional NBA offense, those percentages would probably be in the 50s, too. San Antonio has conceded mid-range jumpers and floaters. It has baited the Rockets into shots it knows they don’t want to take. And it has done so to an extent the Rockets clearly aren’t comfortable with. Other teams have tried this, of course, but not many have A) done it this drastically, and B) had the personnel to do it successfully.

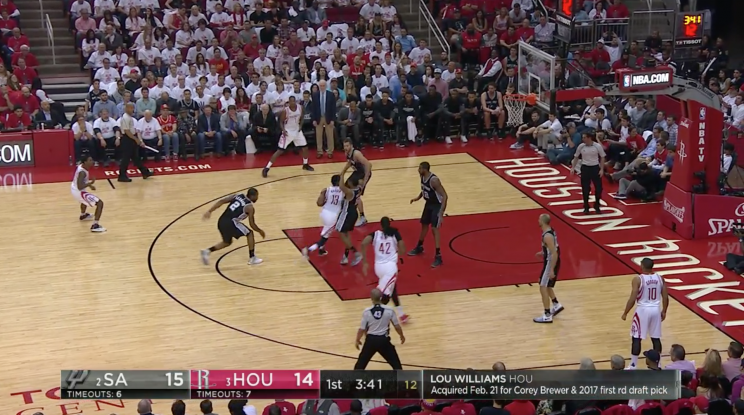

The most obvious example of the strategy is the way the Spurs have dealt with Harden kick-outs. Unlike Aldridge on the Ariza 3-pointer above, secondary defenders rarely had even one foot in the paint in Game 3, especially when they were guarding Ryan Anderson or Eric Gordon. Look at Manu Ginobili’s positioning here as Harden drives to the opposite side of the rim:

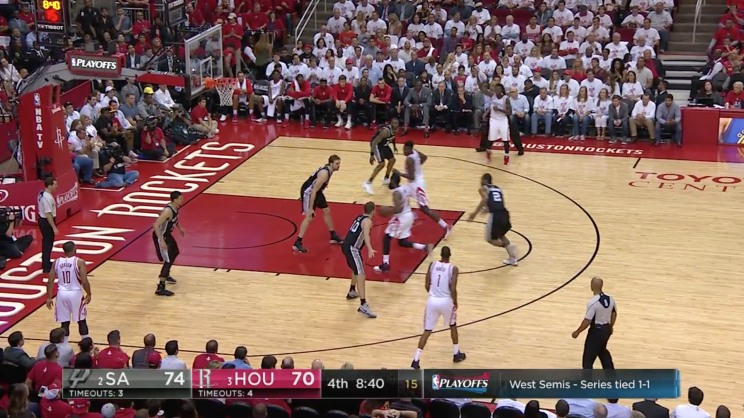

And here’s Danny Green in the fourth quarter, essentially leaving Pau Gasol one-on-two with Harden and Capela so that he can stay within close-out range of Gordon in the corner:

Nonetheless, Harden would often sling his patented lefty cross-court pass, even when a weak-side defender stayed at home on his shooter:

And when a pass did find a shooter, San Antonio’s close-outs were either textbook or overzealous. Or, given the gameplan, both. The Spurs would rather see a mid-range pull-up jumper than any type of 3-pointer, even if the 2-pointer is wide open after a defender has flown by.

On many occasions, the Rockets resisted the Spurs’ bait, but on some, they took it. Houston attempted 13 shots that NBA.com’s play-by-play classified as “floating,” and made just four of them.

Harden was 2-for-3 on floaters, but often passed them up. Instead, he’d pull up for a three, attack the San Antonio big man at the rim, or dish to a wing. Oftentimes that wing was covered. Harden had 43 points on the night, but just five assists. Aldridge and Gasol actually did a very respectable job confronting Harden when he charged toward the cup. That allowed the Rockets to stay at home on shooters.

The Spurs varied their pick-and-roll coverages, at times hedging and going under, at times trailing Harden and zoning up. When they did zone up — when the big man sat back in the paint as the on-ball defender fought over and around the screen — Harden had the options of a 17-foot jumper or a 10-foot floater almost without fail; but he rarely took them.

This meant that the one area of the court to which the Spurs weren’t devoting defensive resources wasn’t one the Rockets were taking advantage of. But the Rockets also weren’t as effective at the rim and behind the 3-point line because the Spurs were so keyed in on both. Harden wanted to get others involved, but the Spurs wouldn’t let him.

The Rockets weren’t automatically less effective because the Spurs chose to hone in on their offensive strengths. But they were less effective because the Spurs did so successfully and because Houston didn’t (or couldn’t) take advantage of the side effects of San Antonio’s strategy — namely the vast swaths of empty court between five and 20 feet away from the rim.

Houston’s answer in Game 4 may or may not be to take more mid-range shots. It may or may not be to stick to what has worked and trust that 3-point strokes will return to form. Either way, San Antonio has done remarkably well to solve problems that after Monday’s blowout almost felt unsolvable.