On spending, Kansas Sen. Roger Marshall brings aggressive House tactics to the Senate

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

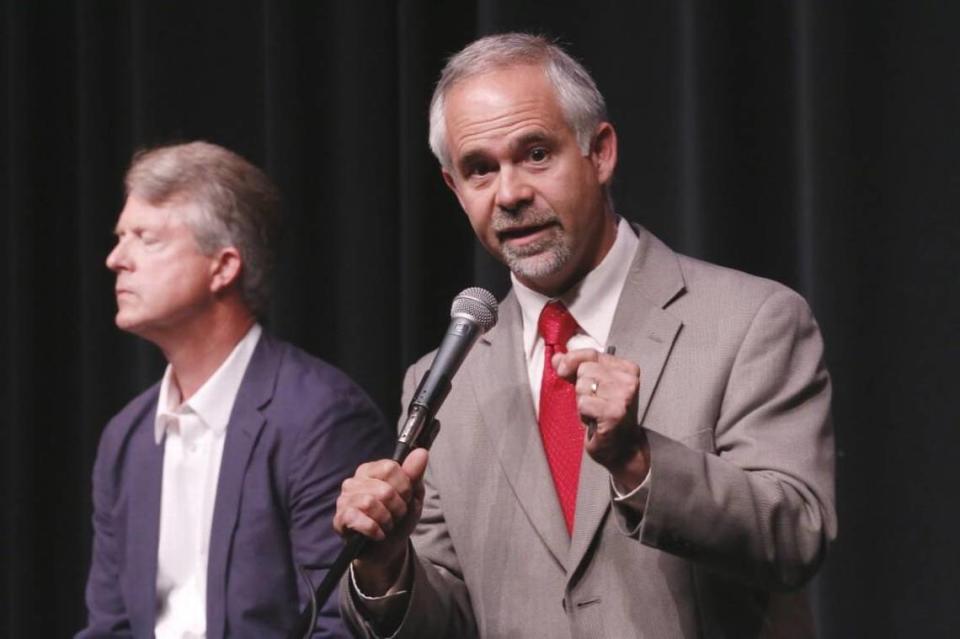

As the Senate stayed late in the night, attempting to avoid a partial government shutdown, Sen. Roger Marshall rose with a proposal.

The first-term Kansas Republican would scrap the temporary, one-week extension of last year’s budget for some federal agencies. Instead, he would keep last year’s budget in place for a year, tacking on additional military aid for Israel.

“Today we feel the pain of the disease of a failed congressional budget process, which gives too much power to too few people,” Marshall said on the Senate floor. “But just like American families, the American government needs to learn to live within its means.”

It was a scene that could have played out in the House, where conservatives have pushed for the longer extension because it would guarantee a 1% cut to some federal spending, locking in savings of about $70 billion to the country’s $34 trillion national debt.

As Congress has spent the past six months struggling to agree on how much money the government should spend in the 2024 fiscal year, which began in October, Marshall has continued to push for steep budget cuts – even after House and Senate leadership came to an agreement on how much to spend.

Marshall’s positions have been aligned with House Republicans, who are driven by a hard-line caucus seeking more conservative policies and led by Speaker Mike Johnson. But Republicans face a steep climb because they control just the House, while Democrats control the White House and Senate.

The Kansas senator’s motion last Thursday ultimately failed – winning support from only 14 Republican senators. But it was another sign of an ongoing institutional change, with a new generation of conservative senators increasingly willing to adopt an aggressive posture in a chamber that is supposed to embody cautious deliberation.

The motion marked Marshall’s second attempt to secure a full-year continuing resolution in two weeks and his second attempt at trying to push military aid for Israel through the Senate, stripped of any support for Ukraine. He has voted no on three measures to temporarily keep the federal government running, as he pushes for steep budget cuts to help decrease the national debt.

“I would just say that Speaker Johnson and my priorities are very similar,” Marshall told The Star. “And I think it’s probably as much a coincidence but certainly trying to figure out something that can pass there and here at the same time. That’s consistent with my priorities as well.”

Marshall was first elected to Congress in 2016 by unseating a conservative seen as an obstructionist. He won election to the Senate in 2020 as an alternative to Kris Kobach, a staunch Trump supporter who was seen as a liability in a general election.

But as a divided Congress has effectively ground to a halt over the past two years, repeatedly struggling to pass major legislation to fund the government, reauthorize key federal programs and provide military aid – Marshall has become a loud voice pushing Senate Republicans to take a tougher approach to major legislation, more aligned with Trump’s populist base.

“I do think that there’s a group of us that are more populist, for lack of a better term,” Marshall said. “When I came to Congress, I didn’t know exactly what my label would be, but it certainly appears I’ve taken up quite a few populist opinions and concerns.”

Both Marshall and Johnson were elected in 2016, the same year as Trump. While Marshall backed former Ohio Gov. John Kasich, a moderate, in the 2016 Republican presidential presidency, he quickly got on board with Trump’s agenda, voting with his desired policies 98% of the time.

They entered a House Republican Caucus, where hard-line conservatives aligned with the Tea Party movement of the 2010s had been steadily growing in power.

Using the procedural mechanisms of the House, the lawmakers, called the House Freedom Caucus, became a thorn in the side of Republican speakers seeking to pass legislation through Congress, by pushing legislation that was often unlikely to clear the 60 vote threshold required in the Senate. The group was willing to use hardball tactics, like forcing government shutdowns, in order to negotiate more conservative deals.

Former House Speaker John Boehner, an Ohio Republican, once called a leader of the caucus a “legislative terrorist.”

Casey Burgat, a political science professor at George Washington University, said the new group of senators seems to be adopting some of the tactics of the House Freedom Caucus in the Senate.

“They’re using these must-pass vehicles, which by the way, is what the Freedom Caucus started doing too, kind of hijacking what used to be known as the non-touchables and using those because they recognize the leverage associated with a must pass piece of legislation,” Burgat said.

‘There’s a difference’

Marshall was never associated with the House Freedom Caucus when he served in the lower chamber. In fact, he unseated Tim Huelskamp, who lost his seat on the House Agriculture Committee after then-Speaker John Boehner considered him “disloyal” to the agenda of House Republicans.

Eric Pahls, who ran Marshall’s 2020 Senate campaign, said there’s a difference between being an obstructionist, like Huelskamp, and what Marshall is attempting to do in the Senate.

“He got elected to Congress by taking out somebody who was considered an obstructionist,” Pahls said. “It’s really easy to sit there and vote no on everything or vote yes on everything. I don’t think that voting yes on the big things that DC wants you to vote yes on is productive.”

Pahls said he views Marshall as a member of a “do-something” caucus, where he tries to get action on his campaign pledges, rather than serving as a reliable vote for Senate leadership.

“There’s a difference between fighting the things you disagree with, and building bridges on the things that you can agree on, and full-on obstructionism,” Pahls said.

Marshall has attempted to find common ground on legislation. He teamed up with Sen. Dick Durbin, an Illinois Democrat, on a bill that would eliminate swipe fees (and earned the ire of large banks and credit card companies). He’s also teamed up with Sen. Bernie Sanders, a Vermont Independent, to address a shortage of doctors and nurses who focus on primary care.

His Cooper Davis Act, which requires social media companies to tell law enforcement about social media accounts that are selling drugs, has also picked up bipartisan support.

But all of those bills have yet to pass the Senate. And Marshall’s attempts to force votes on some items in his agenda, like the military aid bill that only focuses on Israel have been blocked by other Senators.

“It hasn’t worked that much,” Burgat said. “The Senate works in a very different way than the House. It’s obviously not a majoritarian institution in the same way. So as much as they want to try to force their behaviors they’re going to have a tougher hill to climb than some House Freedom Caucus members.”

Still, it allows Marshall to project an image of action. While he knows the legislation is likely to be blocked, he can tell voters he tried to pass something but it failed because of the political establishment. That type of language appeals to many in the Republican base, who have sought out candidates they believe will fight against the status quo in Washington – even if they don’t always deliver.

As Trump has reshaped the Republican Party, its core voters have begun to expect lawmakers to mold themselves in Trump’s brash, fighter image, rather than as politicians seeking compromise. When other senators have sought compromise, they’ve often faced censures from their state Republican parties.

Sen. Josh Hawley, a Missouri Republican who has frequently called for the Republican Party to take a more populist approach, says he believes those voters are sending more lawmakers who are looking to break up the status quo in Washington.

“If you look at who leans more in that direction, who’s willing to break the kind of old GOP orthodoxy that’s lost elections for the last 30 years, it’s folks who were elected more recently,” Hawley said. “And Roger’s one of them.”