Special Report: How Egypt's crackdown on dissent ensnared some of the country's top judges

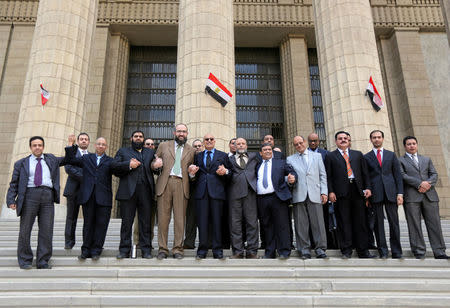

By Ahmed Aboulenein CAIRO (Reuters) - On the evening of July 21, 2013, dozens of judges gathered on the Armada, a floating restaurant docked where the Nile glides past the leafy suburb of Maadi in southern Cairo. The judges, some of whom ranked amongst the most senior in Egypt, were there to break the Ramadan fast. As they tucked into grilled kebab and tahina, the men discussed the military takeover that had taken place three weeks earlier. Led by General Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, a former head of military intelligence, Egypt's military had ousted President Mohamed Mursi and his government following mass popular protests against his rule. Mursi, a member of Islamist group the Muslim Brotherhood, had been democratically elected a year earlier. Now he was in jail. One of the judges, Mohamed Nagi Derballah, suggested issuing a statement condemning the takeover. The document he drafted that evening called for a return to "constitutional legitimacy" – a democratic government – but steered clear of directly criticizing the military or demanding Mursi's reinstatement. More than 30 judges signed the document that night. Over the following days others added their names, including some living abroad. Ultimately, 75 judges signed the statement. A senior judge read it out at a news conference on July 24. Three years on, nearly half the judges who signed the statement have been removed from office as part of what they say is a crackdown by Sisi aimed at bringing the judiciary under tighter government control. Judicial records show that since 2013, disciplinary committees formed by the Supreme Judiciary Council, the governing body which sits on top of the Egyptian judicial ladder, have forcibly retired 59 judges – including 32 of the 75 who signed the Armada statement. Some of the judges who signed the Armada letter recanted and were not disciplined. An Egyptian judicial disciplinary committee has the power to reprimand judges, transfer them to other posts, force them to retire, or clear them of wrongdoing. After the committee rules on a case, Sisi signs off on the decision. Most of the 59 judges forced into retirement were ruled to have broken a law that prohibits judges from "practicing politics." But 25 of the judges told Reuters they believe the real reason they were pushed out was to scare other judges into toeing the government line. They say their dismissals were a deliberate attack on one of the last institutions that can check the power of the state and protect Egyptians' basic freedoms. "They (the state) don't want to allow any dissenting voices. We should all have the state's point of view," said Mohamed Zein al-Abedeen, who at 35 was the youngest to be forced out. Ahmed al-Khatib, another of the judges to lose his job, said, "Anyone who is a reformist or has critical opinions gets filtered out. They (the state) are targeting those calling for judicial reform or judicial independence." Repeated phone calls and emails to Sisi's office for comment went unanswered. The country's justice ministry denied there was any attempt to reshape the Egyptian judiciary. "The idea of revenge against specific judges or reshaping the judicial branch is absolutely not true. We have in Egypt the principle of judicial independence," Judge Khaled al-Nashar, the Assistant to the Minister of Justice for Parliamentary and Media Affairs, told Reuters. "The executive branch does not interfere in the affairs of the judicial branch. In all honesty the executive branch does not and will never have the ability to reshape the judiciary. The president himself says openly in speeches that he does not interfere in the affairs of the judiciary." Egypt's judiciary has always enjoyed a degree of independence. Long-serving autocrat Hosni Mubarak, whose ouster by a popular uprising in 2011 opened the way for Mursi's election, mostly relied on military tribunals to silence his opponents. Most judges who spoke to Reuters said that political interference in the judiciary used to be relatively rare. Sisi has been more prepared to intervene. Elected president in 2014 a year after he seized power, he has cracked down on Islamist opposition groups, secular activists, journalists, students – and, the judges say, the judiciary. "The judiciary in Egypt is being used as a tool by the regime for revenge," said Judge Mohsen Fadli, a former deputy to Egypt's top judge and another who said he was forced to retire because he signed the Armada statement. The judges also allege that former colleagues who helped force them out did so because it was likely to advance their own careers. Three senior judges have been made justice minister since 2013, including the incumbent. The three had submitted legal complaints against colleagues, ruled that colleagues had broken the law on expressing political opinion, or sat on disciplinary boards. At least seven other judges who submitted complaints against colleagues have been given senior positions in the justice ministry. The judge who drafted the initial complaint against those who signed the Armada letter was Ahmed al-Zend. Until 2015, Zend was the president of the Judges Club, a social group and informal professional association. Zend was extremely critical of Mursi when he was president and publicly backed Sisi after the military takeover. Sisi made Zend justice minister in 2015. Zend could not be reached for comment. Sisi sacked him as minister in March, after Zend told a talk show host on live television that he would imprison anyone who broke the law, even if it were the Prophet Mohammad. Nashar, the justice ministry spokesman, said Zend's appointment as minister was not connected to his role in the Armada case, and that the two other ministers and seven officials were all appointed on merit. Nashar further rejected any suggestion Hossam Abd al-Rehim, the current minister, had benefited from his role in the Armada case. While Abd al-Rehim had been the chair of the Supreme Disciplinary Council as it considered the case, he had been appointed a minister before the judicial disciplinary committee ruled, Nashar said. A DIVIDED BENCH Article 73 of Egypt's Judiciary Act prohibits judges from practicing politics and bans a judge sitting on a case from expressing political opinions. But many of the judges who have been forced out argue that the law allows judges to express political opinions as individual citizens, provided they don't run for office or join a political party. After the overthrow of Mubarak, some judges did start to make their views known – talking to the media, writing editorials and even making speeches at protests and gatherings. A few of those who spoke out at the time were sympathetic to Mursi. Others were open to having an Islamist in power as long as he was democratically elected. Yet others were less supportive of the new president but remained critical of the Mubarak regime and its backers who opposed Mursi. And some judges, including Zend, were openly critical of the new president. Ahmed al-Khatib, who sat on the Cairo Court of Appeals until he was forced out in a separate case (see sidebar), was one of those who took a middle line. He advocated for an independent judiciary and judicial reforms, and sometimes criticized the judiciary and how it was run. But he did not back Mursi. Khatib said the authorities, including the Supreme Judiciary Council, were aware he was making his personal views known publicly "and let it happen, with tacit approval." But Nashar said there was no such approval. Instead, he said, many infractions went on unchecked after the 2011 uprising because the state was "upside down." Once stability was restored, he said, authorities went after those who had broken the law. Zend was another one to make his opinions clear. In June 2012, after Mursi had been elected but before he had been sworn in as president, Zend told a news conference that "If we (judges) had known elections would bring you (Mursi) to power, we would not have overseen them." In a telephone call to a television talk show 10 days after Mursi's inauguration, Zend accused the new president of "advocating a state where the law of the jungle is in effect." Zend was angry that Mursi had recalled parliament, which the Supreme Constitutional Court had earlier dissolved on the grounds that the election law was unconstitutional. Zend continued to speak out against the president, videos from anti-Mursi protests posted online show. The Judges Club, which he headed, openly called for Mursi's ouster. Asked by a television talk show in 2013 if he was practicing politics and thus in breach of the judicial law, Zend answered: "If practicing politics will save Egypt then I will never stop practicing politics." Nashar said that judges such as Zend who supported anti-Mursi protests were not practicing politics, because they did not support a specific political group but spoke in the national interest. Anyone who expressed pro-Sisi sentiments, though, would have overstepped the mark, Nashar said. "There may have been some mistakes that were not noticed," he said. "If there was indeed practicing of politics, which is prohibited, then there should have been a punishment. But perhaps these events were not reported or noticed." THE CASES After Mursi was overthrown and the group of 75 judges called for a return to civilian rule, Zend and 15 other judges drafted a legal complaint against them. The complaint accused the 75 judges of belonging to Mursi's now-banned Muslim Brotherhood movement, spreading lies, slandering the military, abusing their positions, inciting violence, and participating in politics. The judges in question, the complaint said, had "delivered a statement amongst Muslim Brotherhood protesters" at a protest camp and "accused the Egyptian military of usurping legitimacy." All 25 judges interviewed by Reuters rejected those allegations. The Minister of Justice referred the 75 to a disciplinary council set up to hear the case. The council immediately set up an inquiry headed by Judge Sherine Fahmy, an investigative magistrate. According to Judge Fadli, the former deputy to Egypt's top judge and one of those forced to retire, Fahmy was a Zend ally. Fahmy declined to comment on his relationship to Zend. THE INQUIRY The accused judges say the inquiry was a sham. They say fellow judges they brought in to act on their behalf, as is their right, were not allowed to mount defenses. They also say they were not given access to investigation documents, and were not confronted with evidence. Some say they were not informed of the times and locations of several hearings. Reuters has reviewed inquiry documents, legal memos, written testimonies and defense arguments that back those claims. The judges also say, and documents confirm, that only four of the 75 were given the opportunity to defend themselves before the committee. There were other issues. In the report he submitted to the disciplinary committee, investigating magistrate Fahmy concluded that one judge had allowed an Islamist candidate to cheat in 2008 parliamentary elections. But no parliamentary election took place in 2008. In March 2014, 31 of the 75 judges were found to have practiced politics. Those found guilty appealed. The Supreme Disciplinary Council, an internal tribunal of last resort, upheld the ruling in March this year and increased the number found to have breached the law to 32. "MANUFACTURING OF FEAR" One of the youngest of the dismissed judges is 42-year-old Hossam Mikawy. For the first two years after his dismissal, he spent his days in his suburban villa on the outskirts of Cairo where he has set up one of the rooms as a library, television room and kennel for his dog, Hector. Mikawy was banned from traveling outside Egypt but has not been told why. He suspects it is because he used to attend legal conferences in Europe and America and has foreign friends. He recently began a small arbitration service to bring in some money. He says judges like him, young and outspoken, were targeted because they supported the 2011 uprising and pushed for judicial reforms. "It is disgusting that they just label anyone who calls for reform a Muslim Brotherhood member," he said. "Judges are there to protect freedoms ... I did not sign this statement because I wanted to defend Mursi. I would have signed it even if (Mursi's opponent in the presidential election) Ahmed Shafiq was in his place." The statement avoided the word "coup" in order not to take sides, Mikawy said. It simply called on all parties to engage in dialogue and respect election results. "There is a deliberate manufacturing of fear," he said. "Judges are now afraid to issue verdicts that would make the government unhappy. They now know they can lose their jobs." Nashar rejected that and said the government cannot intimidate those it disagrees with because the judiciary is independent and would never allow interference. Another of the judges forcibly retired was Islam Alam al-Din. He said investigators used a photo he had posted on Facebook as evidence against him in the case. The photo showed him at his young son's school in the United Arab Emirates, he said. Alam al-Din was living there because he was on loan to the Emirati court system. But investigators alleged the photo showed the pair "in a Muslim Brotherhood protest camp," Alam al-Din said. Four judges told Reuters that Zend would later formalize the tactic of monitoring social media. They say that when Zend became justice minister in 2015, he formed a department to monitor judges' social media accounts. Ministry spokesman Nashar denied the existence of any such unit: "Monitoring private accounts is a crime. The justice ministry would never get caught up in spying." Nashar said it was possible one of Alam al-Din's Facebook friends had noticed he had expressed a political opinion and reported him. "This indeed happened. But there is no official body tasked with doing this." "NONE OF YOUR BUSINESS" Mohamed Nagi Derballah, the man who drafted the letter, was also forced from his job. Derballah had helped write Egypt's new constitution after the 2011 revolution and was on track to become Egypt's top judge. But after the military took over, it suspended the new constitution and Derballah was charged with practicing politics in two separate cases. Now he has been banned from practicing law and from traveling. Junior judges who once competed for his attention now avoid him in social gatherings, he said. "I didn't even want to be a judge, you know, as a young man. I wanted to write poetry, novels, but the law won," the bespectacled 61-year-old said in his neat Cairo home. Behind him, a bookcase heaved with legal texts on everything from Islamic Sharia to the Napoleonic Code. There were two portraits: his father and the uncle who had convinced him to swap writing for the gavel. At college, Derballah was a supporter of President Gamal Abdel Nasser and his brand of anti-colonial secular nationalism. Nasser's men arrested and tortured Derballah's father twice for belonging to the Muslim Brotherhood, but Derballah remained unmoved. "There were higher goals, more important than my father's arrest. We had massive dreams and could justify anything Nasser did," he said. Derballah's brother was an Islamist who rose to the top of al-Gama'a al-Islamiyya, which fought an insurgency against the Egyptian government between 1992 and 1998. The group killed almost 800 policemen and dozens of foreign tourists before renouncing violence. Derballah, though, said he has never been an Islamist and did not support Mursi. He proudly recalls a meeting in which he criticized Mursi to his face for attempting to reshape the judiciary and granting himself new powers. Derballah said he had been bound by oath to protect the election results, which was why he signed the Armada statement. But Nashar, the justice ministry spokesman, said a judge's role ends after ensuring a free and fair election. If popular will turns against a freely elected president, he said, "it is none of your business as a judge." (Edited by Simon Robinson)